Okay, I have to discuss something this week that has been bugging me. I have had several emails as of late suggesting one of the biggest investing fallacies stated during late stage bull market advances.

“I don’t care about the price, I bought it for the yield.”

First of all, let’s clear up something.

Company ABC is priced at $20/share and pays $1/share in a dividend each year. The dividend yield is 5% which is calculated by dividing the $1 cash dividend into the price of the underlying stock.

Here is the important point. You do NOT receive a “yield.”

What you DO receive is the $1/share in cash paid out each year.

Yield is simply a mathematical calculation.

The distinction will become important in just a moment. But first, I need to touch on one of the primary issues currently being ignored by the markets which is the inherent risk of mean reversions.

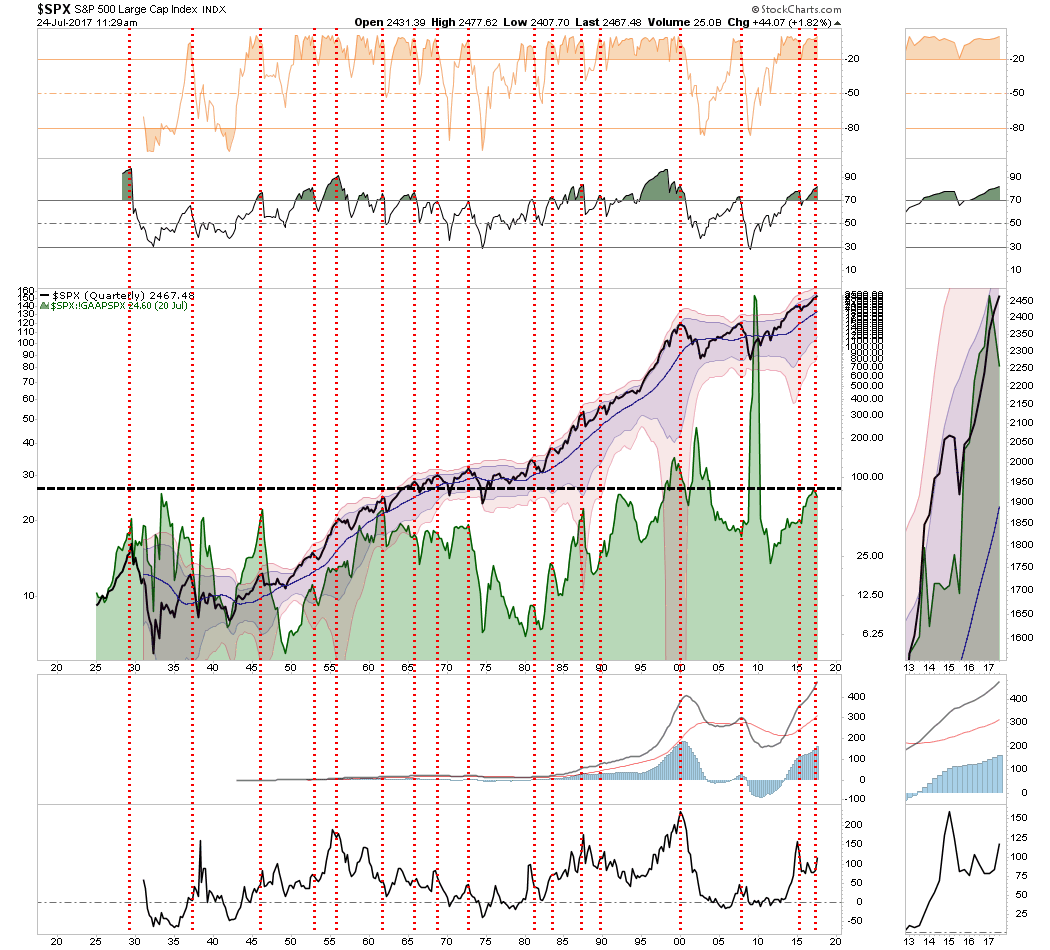

Mean reversions are one of the most powerful forces in the financial markets as, like gravity, moving averages provide the gravitational forces around which prices oscillate. The chart below shows the long-term view of the S&P 500 as related to its long-term 6-year moving average.

Not surprisingly, when prices deviate too far from their underlying moving average (2-standard deviations from the mean) there is generally a reversion back to the mean, or worse.

As you will notice, the bear markets in 2000 and 2007 were not just reversions to the mean, but rather a massive reversion to 2-standard deviations below the mean. Like stretching a rubber band as far as possible in one direction, the snapback resulted in devastating bear markets.

While these bear markets did result in subsequent bull markets, as they should, at the peak of each cycle it was believed that somehow “this time was different.” As discussed previously, the current bull market, which is also believed to be different, is likely not given the lack of economic dynamics required to foster an extended secular period.

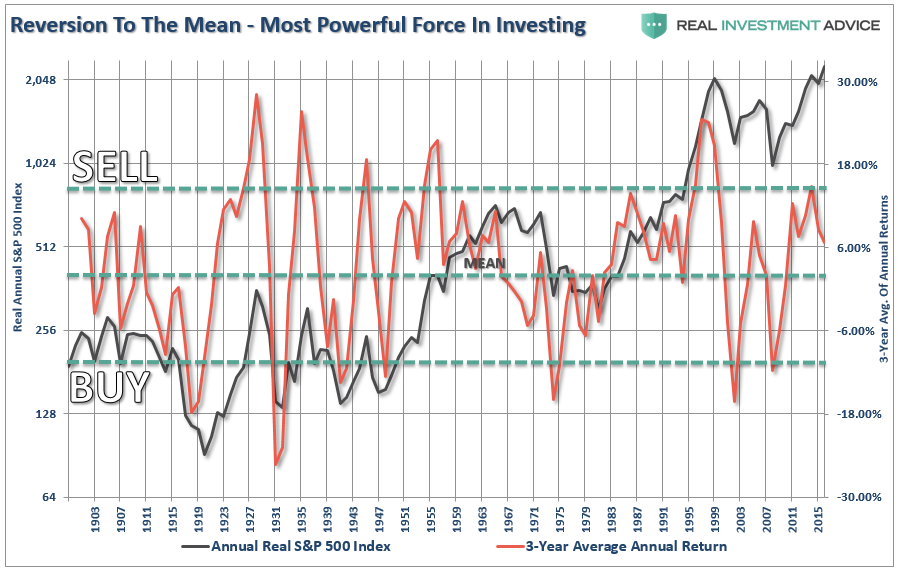

The chart below brings this idea of reversion into a bit clearer focus. I have overlaid the 3-year average annual real return of the S&P 500 against the inflation-adjusted price index itself.

Historically, we find that when price extensions have exceeded a 12% deviation from the 3-year average return of the index, the majority of the market cycle had been completed. Following the large spike in 3-year annualized returns in 2014, returns have begun to revert and will likely continue to do so into the next bear market cycle.

While this analysis does NOT mean the market is set to crash, it does suggest that a reversion in returns is likely. Unfortunately, a historical reversion in returns has often coincided, at some juncture, with a rather sharp decline in prices.

I Bought It For The Dividend

This brings me to the “I Bought It For The Dividend” investing problem.

I previously posted an article discussing the “Fatal Flaws In Your Financial Plan” which, as you can imagine, generated much debate. One of the more interesting rebuttals was the following:

“‘The single biggest mistake made in financial planning is NOT to include variable rates of return in your planning process.’

This statement puzzles me. If a retired person has a portfolio of high-quality dividend growth stocks, the dividends will most likely increase every single year. Even during the stock market crashes of 2002 and 2008, my dividends continued to increase. It is true that the total value of the portfolio will fluctuate every year, but that is irrelevant since the retired person is living off his dividends and never selling any shares of stock.

Dividends are a wonderful thing, Lance. Dividends usually go up even when the stock market goes down.”

This comment drives to the heart of the “buy and hold” mentality and, along with it, many of the most common investing misconceptions.

Dividends Always Increase, Right?

Let’s start with the notion that “dividends always increase.”

First, his statement is incorrect because during market reversion “cash dividends” DO NOT increase – but the YIELD does because of the collapse in prices.

But, more to the point, the notion is true, until it isn’t.

During the 2008 financial crisis, more than 140 companies decreased or eliminated their dividends to shareholders. Yes, many of those companies were major banks, however, leading up to the financial crisis there were many individuals holding large allocations to banks for the income stream their dividends generated. In hindsight, that was not such a good idea.

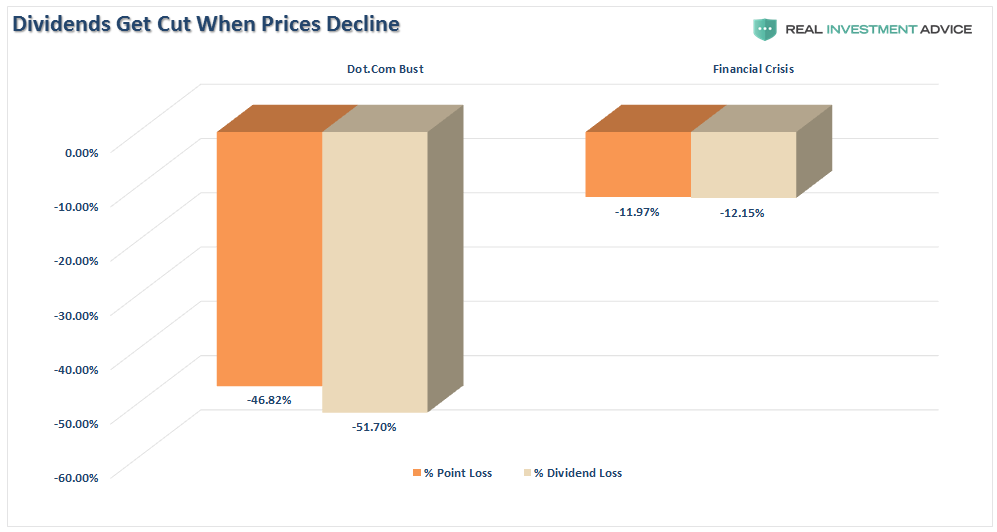

But it wasn’t just 2008. It also occurred dot.com bust in 2000. In both periods, while investors lost roughly 50% of their capital, dividends were also cut on average of 12%.

Of course, it wasn’t EVERY company cutting dividends by 12%. Some didn’t. Many did and some even eliminated their dividends entirely to protect creditors.

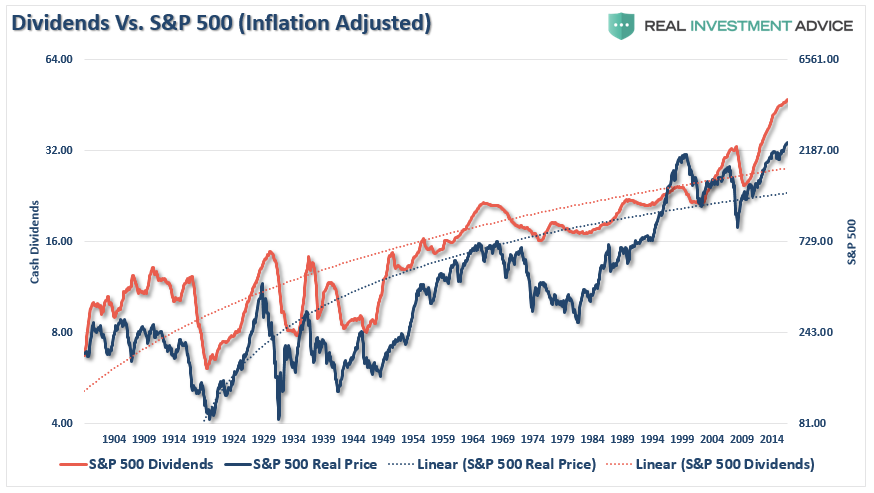

Due to the Federal Reserve’s suppression of interest rates since 2009, investors have piled into dividend yielding equities, regardless of fundamentals, due to the belief “there is no alternative.” The resulting “dividend chase” has pushed valuations dividend yielding companies to excessive levels disregarding underlying fundamental weakness.

As with the “Nifty Fifty” heading into the 1970’s, the resulting outcome for investors was less than favorable. These periods are not isolated events. There is a high correlation between declines in asset prices and the actual dividends being paid out throughout history.

While I completely agree that investors should own companies that pay dividends (as it is a significant portion of long-term total returns), it is also crucial to understand that companies can, and will, cut dividends during periods of financial stress. During the next major market reversion, we will see much of the same happen again.

It is during these times when prices collapse, and dividends are slashed, the “I bought it for the dividend plan” doesn’t work out.

EVERY investor has a point, when prices fall far enough, that regardless of the dividend being paid they WILL capitulate and sell the position. This point generally comes when dividends have been cut and capital destruction has been maximized.

Psychology

Of course, while individuals suggest they will remain steadfast to their discipline over the long-term, repeated studies show that few individuals actually do. This was shown clearly in the 2016 Dalbar study that I discussed in “You Still Suck At Investing:”

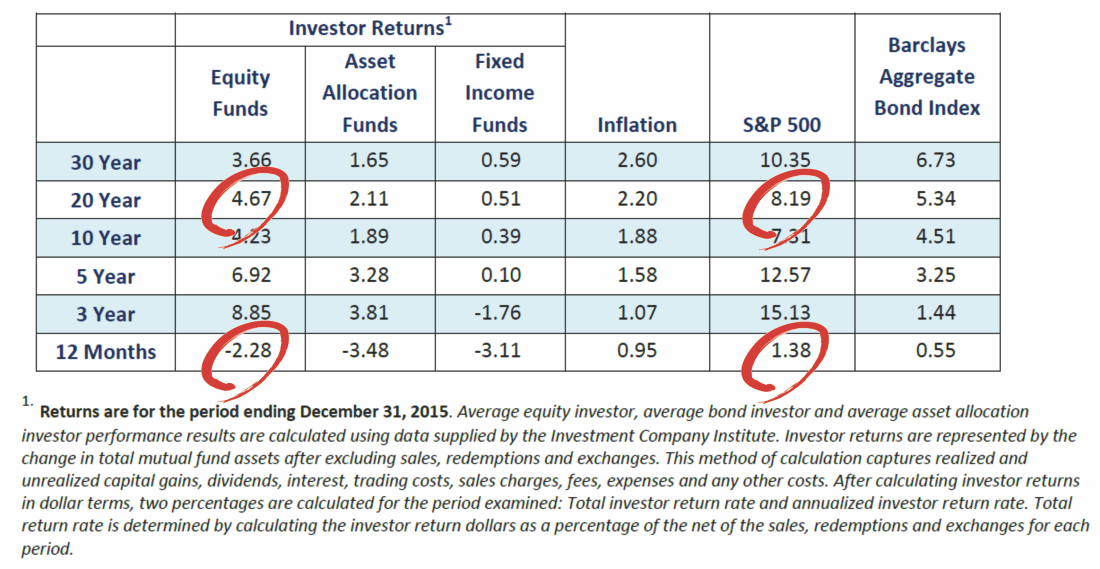

“However, even the issues shown above do not fully account for the underperformance of investors over time. The key findings of the study show that:

- In 2015, the average equity mutual fund investor underperformed the S&P 500 by a margin of 3.66%. While the broader market made incremental gains of 1.38%, the average equity investor suffered a more-than-incremental loss of -2.28%.

- In 2015, the average fixed income mutual fund investor underperformed the SPDR Barclays Aggregate Bond Index (NYSE:BNDS) by a margin of 3.66%. The broader bond market realized a slight return of 0.55% while the average fixed income fund investor lost -3.11%.

- In 2015, the 20-year annualized S&P return was 8.19% while the 20-year annualized return for the average equity mutual fund investor was only 4.67%, a gap of 3.52%.”

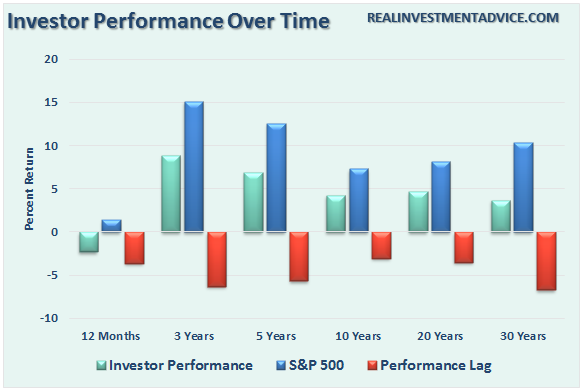

“Here is a visual of the lag between expectations and reality.”

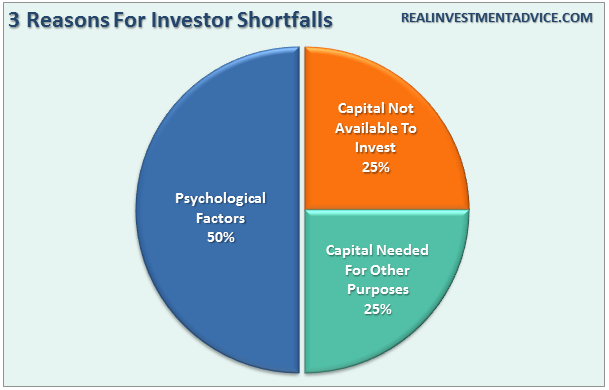

“Accordingly to the Dalbar study, the three primary causes for the chronic shortfall for both equity and fixed income investors is shown in the chart below.”

Notice that while “fees” are important to overall returns, “fees” are not a key issue to the majority of underperformance by individual investors. As shown above, the key issues come down to primarily a lack of capital to invest and psychology.

Despite the logic behind “buying and holding” dividend yielding stocks over the long term the biggest single impediment to the success of that strategy over time is psychology. Behavioral biases, specifically the “herding effect” and “loss aversion,” repeatedly lead to poor investment decision-making.

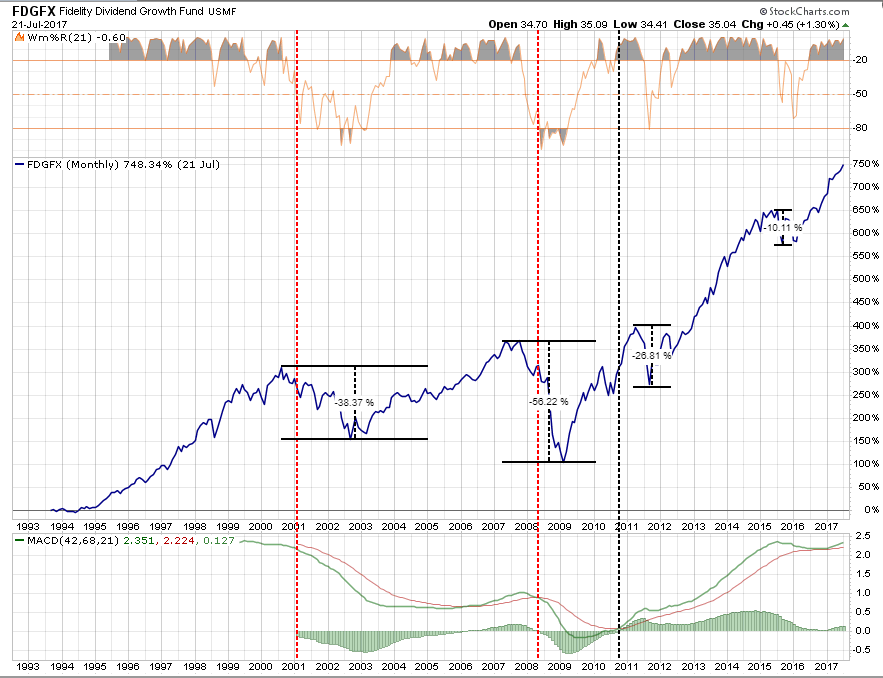

Ultimately, when markets decline, there is a slow realization “this decline” is something more than a “buy the dip” opportunity. As losses mount, so does the related anxiety until individuals seek to “avert further loss” by selling. It is generally believed that dividend yielding stocks offer protection during bear market declines. The chart below is the Fidelity Dividend Growth Fund (most ETF’s didn’t exist prior to 2000), as an example, suggests this is not the case.

As you can see, there is little relative “safety” during a major market reversion. The pain of a 38% loss, or a 56% loss, is devastating particularly when the prevailing market sentiment is one of a “can’t lose” environment. Furthermore, when it comes to dividend yielding stocks, the psychology is no different – a 3-5% yield and a 30-50% loss of capital are two VERY different issues.

In the end, we are just human. Despite the best of our intentions, it is nearly impossible for an individual to be devoid of the emotional biases that inevitably lead to poor investment decision-making over time. This is why all great investors have strict investment disciplines that they follow to reduce the impact of human emotions.

While many studies show that “buy and hold,” and “dividend” strategies do indeed work over very long periods of time; the reality is that few will ever survive the downturns in order to see the benefits. Furthermore, with valuations and market correlations at extremely elevated levels, the next major market correction will be equally unkind to all investors. But then again, since the majority of American’s have little or no money with which to invest, maybe that is the bigger problem to begin with.