In this past weekend’s newsletter, I addressed three of my concerns for the markets going forward.

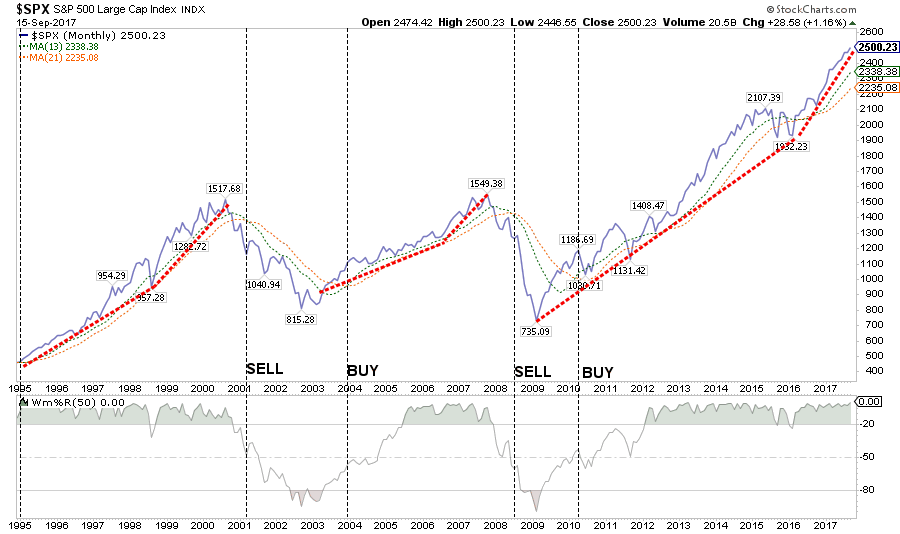

Chart 2) One of the hallmarks of a late-stage bull market cycle is the acceleration in price as investors capitulate by “jumping in” as prices accelerate. While the long-term moving averages currently suggest the bull cycle is intact, we will watch for the crossover to give us an indication of when to leave.

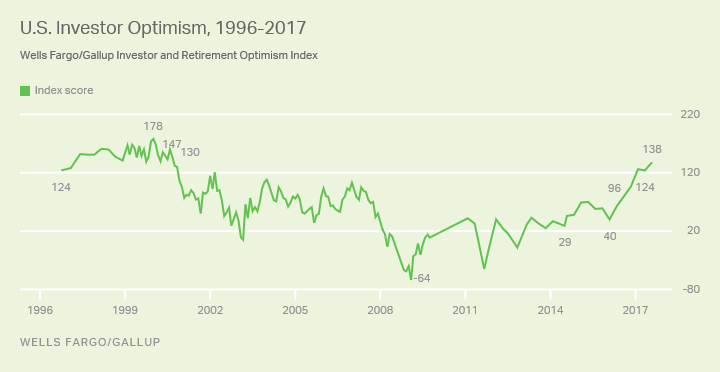

The acceleration in the increase of prices is a hallmark of “exuberance” in the markets. Not surprisingly, the sharp increase in asset prices, as the markets broke through successive barriers of 2200, 2300, 2400 and 2500, has spurred investor optimism to the highest levels in 17-years as noted last week:

The latest boost in optimism pushes the index almost 100 points higher than the +40 score measured in February 2016. The 98-point hike over the past 18 months is the largest increase in the 20-year history of the index that is not a rebound immediately after a major drop in optimism.

After more than 8-years of a surging bull market, often declared the ‘most hated in history,’

- Sixty-eight percent now say they are optimistic about the stock market’s performance during the next year, matching the record high for the question from December 1999 and January 2000.

- At least 61% have expressed optimism about the stock market in each of the three surveys this year, a percentage matched or exceeded only four other times in the 132 times the question has been asked since April 2000.

- Twenty-five percent say they are ‘very optimistic,’ topping the previous record high of 24% from the first quarter of this year. Only 11% were very optimistic a year ago.

- Sixty-one percent of investors now say it is a good time to invest in the stock market, up from 53% two years ago. Among those saying it’s a good time to invest, the main reason is their belief that the market will continue to increase, mentioned by 47%.”

As Robert Shiller penned for the NYT, that surge in optimism is symptomatic of a bigger issue:

Canny stock investors are like judges in a quirky beauty contest. They aren’t looking for real beauty but for qualities that other people believe still other people will find beautiful.

That was the observation of John Maynard Keynes, who suggested that investors do not actually make money by picking the best companies, but by picking stocks that waves of other traders will want to buy.

Investing, in other words, is an exercise in mass psychology.

The belief that Central Banks have the markets under control is a dangerous one. While many believe that just a few Central Bankers have the foresight and capability to control a market driven by human emotion and frailties, such is unlikely to be the case. This was a point John Mauldin clearly made this past weekend:

This time is different are the four most dangerous words any economist or money manager can utter. We learn new things and invent new technologies. Players come and go. But in the big picture, this time is usually not fundamentally different, because fallible humans are still in charge. (Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart wrote an important book called This Time Is Different on the 260-odd times that governments have defaulted on their debts; and on each occasion, up until the moment of collapse, investors kept telling themselves ‘This time is different.’ It never was.)

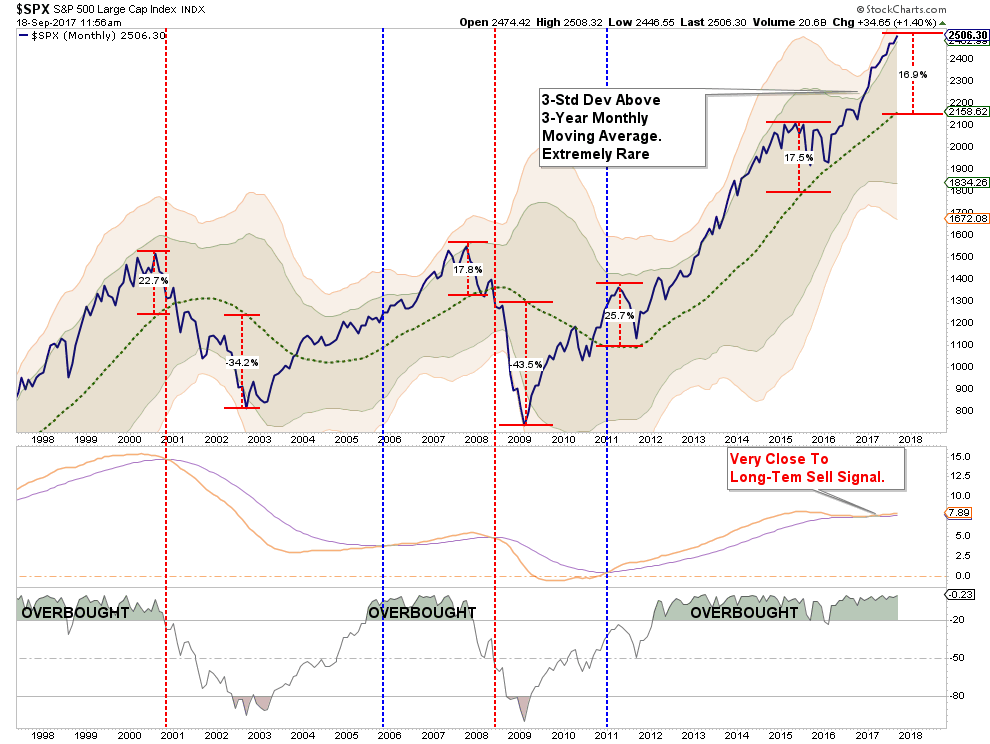

As shown in the chart below, which is monthly price data, the market is trading 3-standard deviations and nearly 17% above its 3-YEAR moving average. Such extensions and deviations have generally not lasted long, but are evidence of the bullish psychology driving the market.

I agree with Dr. Shiller that such does NOT mean there is a crash coming tomorrow:

But the result is that while valuations remain very high there just doesn’t seem to be much evidence that many investors in the United States stock market are actively worrying today that other investors are on the verge of selling. Mass opinions may well change, but for now, in the critical psychological dimension, the stock market does not closely resemble the market in the dangerous years of 1929 or 2000.

That doesn’t mean that there is no danger of a crash. But at the moment, the psychological preconditions for a spiraling downturn don’t appear to be in place.

As is always the case in late-stage bull market advances, the need to chase performance overrides the logic of investing for the long-term. More importantly, mass opinions can change extremely quickly. Like a slow leak in the hull of a ship, it will begin slowly, but the eventual rupture will send participants scrambling for the lifeboats.

You can’t blame individuals really. They are inundated daily by media-driven commentary that pushes them to “jump in because they are missing out.” This sense of urgency to be invested leads to performance chasing of things that have already done well. As I have shown previously, there is substantial evidence that buying last year’s “winners,” more often than not, turn out to be this year’s “losers.”

Rob Arnott, Vitali Kalesnik and Lillian Wu of Research Affiliates made a brilliant point about the danger of performance chasing:

Joe Kennedy famously said on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash: ‘When shoeshine boys have tips, the stock market is too popular for its own good.‘

The negative relationship between a manager’s past and future simple returns means that when your cab driver or bartender (shoeshine boys are less common these days) tells you about an investment with recent double- or triple-digit returns—beware! That may just be the signal to stay away from the market, and most particularly, from the winningest funds. Reciprocally (from repeated personal experience in 1974, 1982, 1987, 2002, and 2009), when you hear reasonably savvy people saying they’ll never invest in stocks again, chances are stocks are at extremely low valuations and are a bargain.

In other words, investing successfully is, in part, learning to do what is uncomfortable in the short-term.

As Research Affiliates concludes:

Because it’s impossible to know where the top is, and we don’t want to sell too soon, ‘selling high’ is not easy. When we sell high, and the asset moves higher, we feel foolish. ‘Buying low’ is even harder. Anything that’s newly cheap has inflicted pain and losses in its path to low prices. It’s impossible to know where the bottom is, so buying low inevitably leaves us looking and feeling foolish until the turn. ‘Buy low, sell high’ is therefore a painful path to success.

Nevertheless, we hope our findings encourage investors to consider joining us in moving out of our respective comfort zones. The capital markets do not reward comfort. In investing, we generally find our best rewards in our discomfort zone.

Holding higher levels of cash than normal, trimming back winning positions, and selling losing ones are all steps which “go against the grain” in the current market. As noted, it’s hard to think you are “missing out” as others may be getting ahead of you.

But, investing isn’t a competition. There are no winners, just losers when you get it wrong.

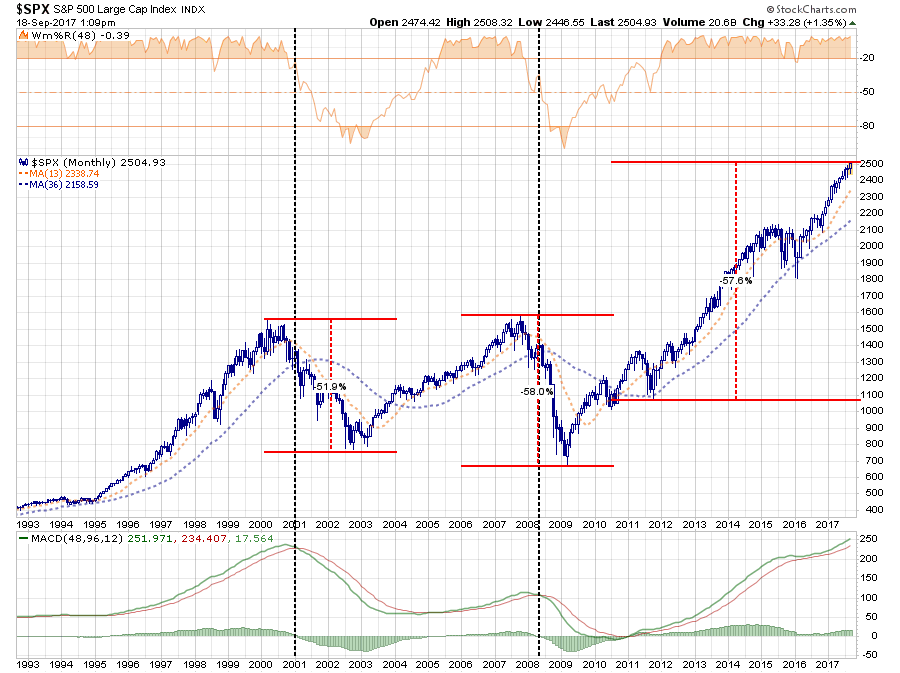

Just remember the one final chart below.

From the current levels of over valuation, excess extension and extreme bullishness which currently exists, the coming reversion “beyond” the mean will wipe out the majority of any gains made over the last several years. Such is the case with all reversions throughout history.

Worrying about “missing out” on the current bull market should probably not be at the top of your list.