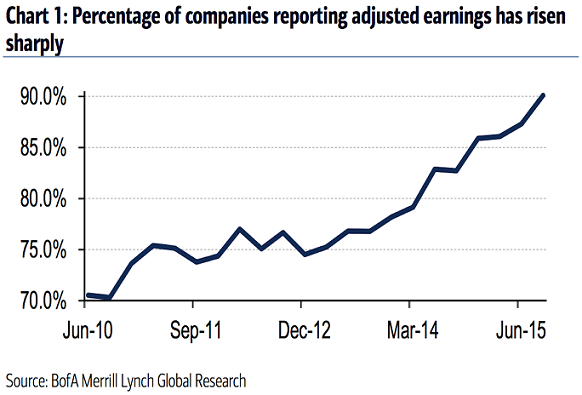

The times they are a changin’. In the ’80s as well as the ’90s, corporations reported quarterly results that corresponded to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). These days, the vast majority of companies report “pro-forma” earnings that adjust for unusual, special or one-time circumstances.

Take a look at the dramatic rise in the percentage of companies serving up adjusted profits per share rather than GAAP-based results. In June of 2010, 70% provided adjusted earnings. However, as the pressure to engineer gains in bottom-line profitability has mounted, more and more corporations have resorted to non-GAAP reporting. Roughly 90% of companies felt the need to manipulate their presentations to the public by June of 2015.

Not a big deal, you say? The S&P 500 SPDR Trust (N:SPY) trading at 193.75 represents a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of roughly 16.5 only if you incorporate pro-forma earnings. If you are inclined to employ GAAP earnings – the less manipulated version of reported earnings – the P/E moves up to approximately 21.5. In other words, even with the S&P 500 close to 200 points below its high-water mark, stocks are not exactly the cellar-dwelling bargain that a value investor craves.

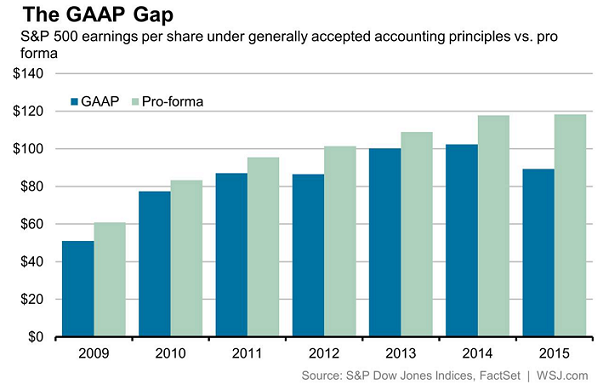

In truth, S&P 500 earnings peaked in 2014. You wouldn’t know it from a year-by-year presentation of pro forma/adjusted results alone. You might have believed that S&P 500 earnings rose form $60 per share in 2009 to $120 per share in 2014, and that they merely took a breather in 2015 by holding steady near $120 per share.

Unfortunately, you’d have been misinformed. A side-by-side visual comparison with GAAP S&P 500 earnings demonstrates how earnings hit their pinnacle near $100 per share in 2014; meanwhile, there has been a 12.7% erosion to nearly $90 per share in 2015. Earnings per share haven’t fallen that hard since the systemic financial collapse year of 2008.

And that’s not all. There is always a discrepancy between GAAP and adjusted pro forma where adjusted results are going to look better than GAAP. And if the discrepancy is not so egregious, maybe one might be willing to overlook it. In fact, studies conducted with chief financial officers will tell you that the magnitude of chicanery is in the realm of 10% of earnings per share. That is about the average spread across the five year period between 2009 and 2013. In 2014, it’s closer to 20%. In 2015? GAAP is now about 25% lower than adjusted pro forma results. That 25% differential is the widest discrepancy since… well, you guessed it… 2008.

The earnings contraction that began in the 3rd quarter of 2014 is unlikely to turn around quickly. One question that an investor who is allocating his assets in the current environment – economic, fundamental, technical, interest rate policy – is whether or not lower interest rates alone justify paying exorbitant stock premiums. Since earnings peaked on 9/30/2014, low yielding iShares 7-10 Year Treasury (N:IEF) has outperformed the S&P 500 SPDR Trust (N:SPY). The deterioration in earnings has coincided with the relative strength of IEF over SPY. And at present, IEF is in a technical uptrend whereas SPY is in a technical downtrend. Earnings contraction, then, is dovetailing with technical price movement – price movement that has not supported the notion of acquiring expensive stocks on the basis of low rates alone.

Perhaps an extremely bullish stock advocate should look for a tailwind from economic data. Sadly, he/she is unlikely to find it. Wednesday’s reading for February’s U.S. service sector came it at its lowest level in two-and-a-half years. In fact, the flash PMI services index came it at 49.8; a reading below 50 represents is indicative of contraction, not expansion.

What we may be seeing, then, is the high probability that U.S. consumption is not immune to the domestic manufacturing recession or economic woes the world over. In spite of gasoline and energy price savings, Americans have been bolstering their rainy day funds with higher U.S. savings rates. And that rarely fits the narrative for hearty personal consumption expenditures.

In fact, the simplistic notion that cheap energy is a net positive for the consumer-driven U.S. economy has been turned upside down. The primary tailwind for stocks at the present moment are higher oil prices, not lower ones, where the correlation between oil and stocks hovers near 90%. Oil up, stocks up. Oil down, stocks down… and sometimes violently.

In sum, the fundamental picture may not matter much in the near-term when risk taking is indiscriminate. It matters more, however, when there is less demand for a wide range of individual securities, industries, yield-producers and debt instruments of varying credit quality. The latter is what has been transpiring since the spring of 2015.

Not so ironically, the bear market rally that began February 11 has not been accompanied by a diminished demand for “risk-off” assets like SPDR Gold Trust (N:GLD), iShares 20-Plus Year Treasury (N:TLT) and CurrencyShares Yen Trust (N:FXY). These risk-off asset types have essentially held up, even with 5.5% upturn for the S&P 500 SPDR Trust (N:SPY) since 2/11. The fact that shelter-seekers still like precious metals, long-term treasuries and carry trade reversal currencies implies that the worst is not in the rear-view mirror. (Note: Many of these asset types are present in the FTSE Multi-Asset Stock Hedge Index.)