US recession risk continues to fade after running moderately higher in recent months. But a variety of business-cycle metrics have only hinted at trouble without crossing the Rubicon. The main concern was linked to higher market volatility. But the economic data merely wobbled without actually falling down. The lesson, once again, is that mastering the art/science of monitoring and evaluating the business cycle requires a methodology that’s based on a spectrum of data that minimizes the potential for confusing market noise with robust macroeconomic signals.

Last week’s news of a strong rebound in US employment in October is among the latest factors that suggest that the imminent threat of a new recession is low. But the notion that a growth bias continues to prevail has been clear all along. A markets-based view of business-cycle risk has popped recently, as I’ve discussed previously. But the increase in Mr. Market’s implied forecast of trouble never reached the tipping point (see here and here, for instance). More importantly, a broad review of economic numbers routinely advised that there was minimal support for the market’s worries.

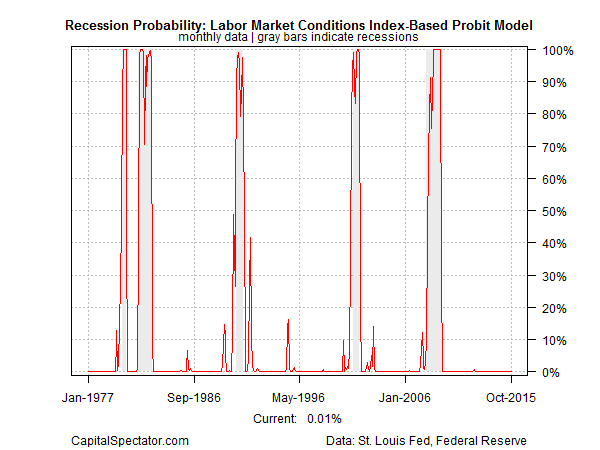

The low-risk outlook for economic risk endures with the current data set. Consider yesterday’s monthly update of the Federal Reserve’s Labor Market Conditions Index, which ticked up to a three-month high in October. Running these numbers through a probit model tells us that the implied risk of a recession for last month was virtually nil.

The econometric case for seeing US macro risk as low extends beyond the employment data. Despite the warnings from the usual suspects in recent weeks that a new recession was assured, my monthly economic profile consistently told us that the recent slowdown in growth was never a clear threat that historically marks the start of downturns (see last month’s update, link above, for instance).

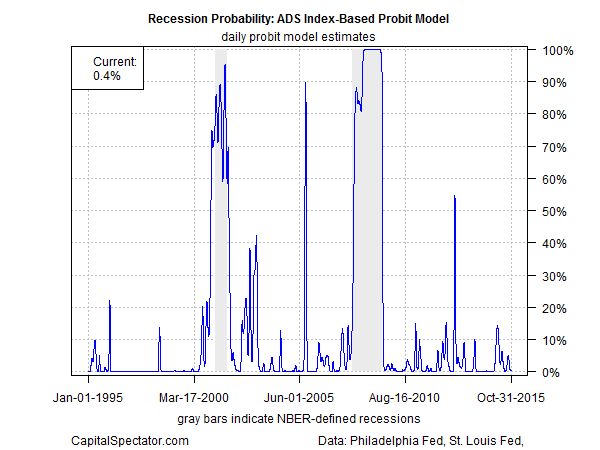

Business-cycle indexes from other sources have dispensed similar messages. The Chicago Fed National Activity Index, for instance, has betrayed minimal signs of heightened business-cycle risk. Ditto for the ADS Index that’s updated throughout each month by the Philadelphia Fed. Note in the chart below that the ADS Index through the end of last month aligns with recession risk at roughly zero percent, based analyzing the data with a probit model.

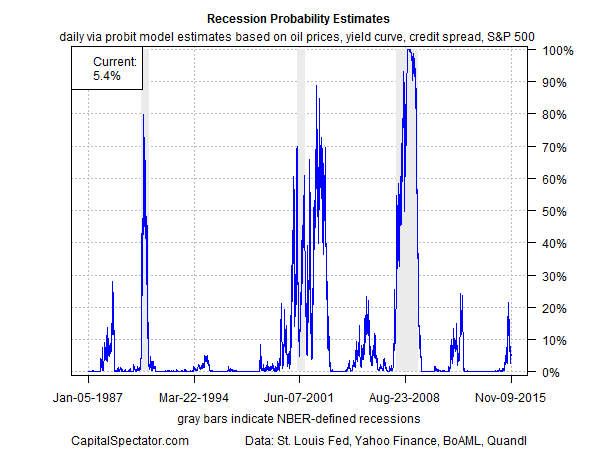

Even a markets-based estimate of US recession risk has faded lately. This real-time approximation of economic conditions via a probit model analyzes four data sets on a daily basis: the US stock market (S&P 500); the Treasury yield curve (10-year yield less the 3-month T-bill yield); the credit spread (BAA-rated bond yield less AAA yield); and spot crude oil prices (based on the US benchmark, West Texas Intermediate). The current estimate has fallen lately, dipping to around 5% as of yesterday (Nov. 9). Even during the height of the recent market correction this measure of recession never topped much above the low-20% range—well below the levels in the early stages of the last two NBER-defined recessions.

Meanwhile, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model is currently (Nov. 4) projecting that fourth-quarter GDP is headed for a modest rebound of 2.3% after Q3’s sluggish 1.5% rise.

Surprising? Not really. The US economic trend has wobbled lately, but the case for expecting the worst was less about the data vs. letting emotion and a selective view of indicators dictate the analysis. A superior methodology, and one that’s been proven valuable once again, is applying a relatively objective analytical lens to a diversified data set. The drama factor is low, compared with the usual suspects. But what you lose in terms of theatrical excitement you more than make up via a higher level of reliability.