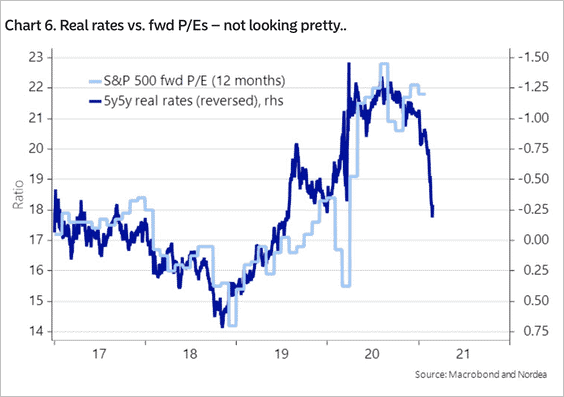

There is a belief on Wall Street that future corporate earnings can only grow in an environment where borrowing is so cheap. Indeed, inflation-adjusted interest rates (a.k.a. “real rates”) are negative, and that means companies are effectively being paid to borrow.

Recently, however, real rates have been on the rise. They’ve nearly flipped from negative to positive.

When real rates are trending in an unfavorable direction, history suggests that investors value stocks at much lower P/E multiples. Five years ago, inflation-adjusted rates were associated with Forward P/Es of 18. That alone might require stocks to reprice 15%-20% lower from the 3900 level on the S&P 500, or 3120-3315.

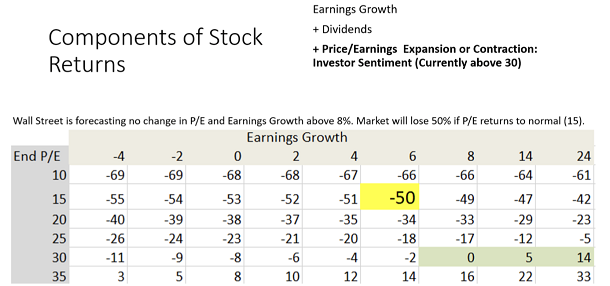

Forward 12-month earnings ‘guestimates’ of how companies may fare are not the only cause for concern. Should actual earnings be adversely affected by rate trends, or should investors be unwilling to pay 30x trailing 12-month earnings due to those rate trends, the stock market repricing could be quite severe.

Consider the math. Even if earnings managed to grow 6%-8% in 2021, P/Es (trailing) that reverted to their mean of 15 could see stocks plummet 49%-50%.

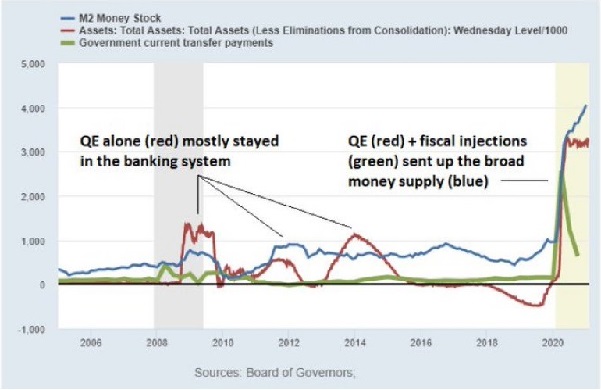

The problem, of course, is the amount of money creation by both the Federal Reserve and the Federal government. When you increase the money supply (M2) by 25% in a single year (blue line below), the printing activity can lead to a loss of purchasing power á la inflation. The financial markets, if left to their own devices, will push interest rates higher to compensate.

It follows that the Fed may choose to intervene, by switching its bond buying of shorter maturities to bond buys of 10-year Treasuries and above. Bringing down 10-year yields would be a preferred method of reigning in borrowing costs.

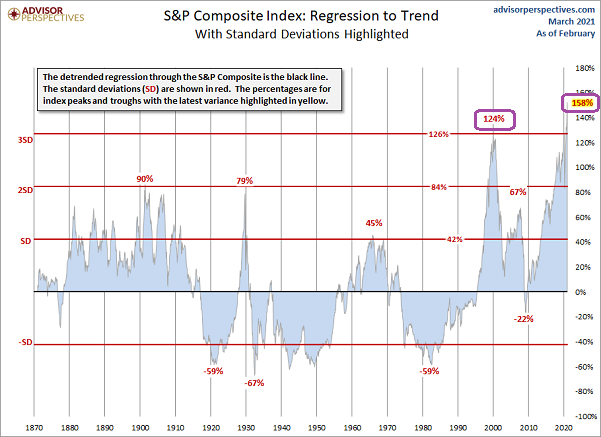

Is it likely to calm volatility in the market? Probably. On the other hand, with the S&P Composite more than 3 standard deviations above trend, any additional scratches on the stock balloon may result in a painful regression to the mean.