In recent decades financial bubbles have been plentiful. From the US housing to the global uranium markets, bubbles seem to be simply inevitable (and generally can not be prevented by regulation or other government interference). In fact bubbles occur even in simulated (experimental) markets (see this paper). Most major asset classes experience a bubble periodically. The tech bubble of the late 90s for example has been one of the better known ones in the equity markets.

Very few have been as spectacular as the one in the so-called rare earth metals that are used to manufacture all sorts of equipment, including LEDs, smartphones, and motors. The rise in prices was triggered by China's policy of limiting exports, creating a perceived shortage. From there hoarding and speculation took hold. And as often happens in commodity markets, the bubble burst almost as violently as it inflated.

Reuters (Scott Barber): As prices soared, new mining projects made it on to the front burner, and some of these are likely to come onstream before the end of the year, including an expansion to Molycorp’s (MCP.N) California operations. China remains by far the world’s largest producer of these materials, but as new supplies elsewhere hit the market while demand remains little changed, China itself also is changing its tune and has announced a higher export quota.

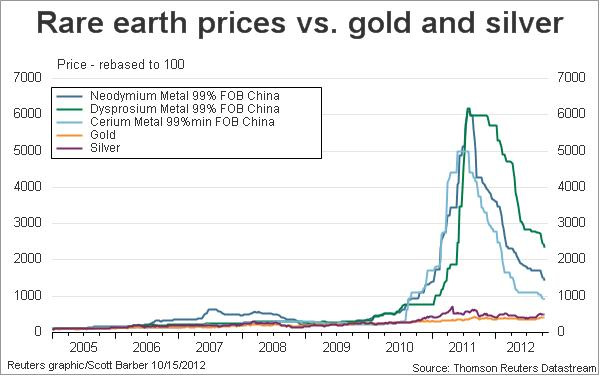

To put the magnitude of this bubble in perspective, the chart below compares the price action of 3 rare earths with gold and silver, which have also appreciated materially over over the same period.

And price declines are continuing. Nations and companies are simply figuring out how to reduce dependence on many of these materials - for example Dysprosium, a metal highly valued for its ability maintain magnetic properties under high temperatures (such as in motors). Japan in particular has been under pressure to adjust because of its loss of supply due to recent tensions with China, the largest producer.

The Asahi Shimbun: TDK Corp., which supplies magnets for motors, has developed a magnet where dysprosium is painted on its surface alone rather than being mixed into the entire magnet body, reducing dysprosium use by half. The company plans to start producing the magnet for automobiles in October.

In February, Panasonic Corp. introduced equipment to extract magnets made of neodymium, another rare earth element, from used home electric appliances at its home appliance recycling plant in Kato, Hyogo Prefecture. The neodymium will be reused in air conditioner compressors and in motors for drum washers and other products, Panasonic officials said.

Honda Motor Co. plans by year-end to start extracting rare earths from nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) batteries used in hybrid vehicles. The automaker's dealerships will collect NiMH batteries from disused hybrid vehicles, and a plant belonging to ferroalloy manufacturer Japan Metals and Chemicals Co. will dismantle them to extract rare earths. Honda will then use the collected material in new hybrid vehicles.

The industry ministry estimates domestic demand for rare earths dropped from 31,000 tons in 2010 to 23,000 tons in 2011.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Popping The Rare Earths Bubble

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.