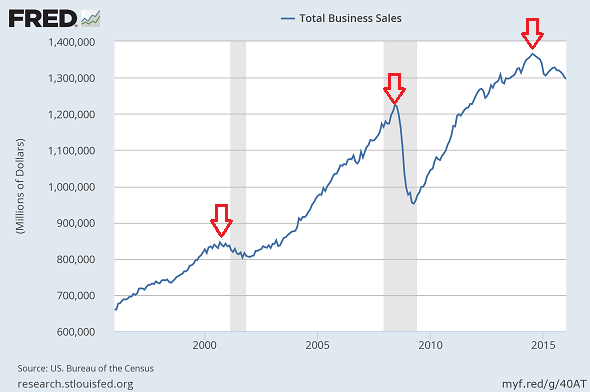

Total business sales – sales by wholesalers, manufacturers and retailers – have fallen 5% from their July 2014 peak of $1.365 trillion. At $1.296 trillion for January 2016, total business sales have dropped back to where they were in January of 2013 ($1.293 trillion). In fact, the erosion of total sales by American businesses are even uglier when one takes inflation into account.

Over the last 20 years, whenever total business sales continued on an upward trajectory, the U.S. economy steered clear of recession. The tech wreck of 2000 and the attacks in September of 2001 resulted in a downward move for business revenue; economic contraction was not far behind. The financial crisis slammed the brakes on business sales in 2008, ushering in The Great Recession; it ended around the same time that businesses began to increase their revenue streams.

Might the year-and-a-half long downturn in revenue generation through January of 2016 be an anomaly? Yes and no. Yes, it is certainly possible that we did not hit “peak sales” in July of 2014; rather, the U.S. economy may still find solid footing in the months ahead. On the other hand, take a look what happened to the U.S. dollar via PowerShares DB US Dollar Bullish (NYSE:UUP) beginning in July of 2014. After years of trading near decade lows, the greenback rocketed 25% against major world currencies. The result? U.S. exporters struggled to sell their wares, commodity prices collapsed and foreign stocks never quite recovered.

The dollar’s vertical move adversely impacted earnings as well. Consider earnings-per-share (EPS) for the S&P 500. More than half of the profits at S&P 500 corporations emanate from overseas, where significantly devalued currencies hindered the proverbial “bottom line.” Specifically, earnings hit a high water mark in Q3 2014 (July-September). Earnings have been falling ever since.

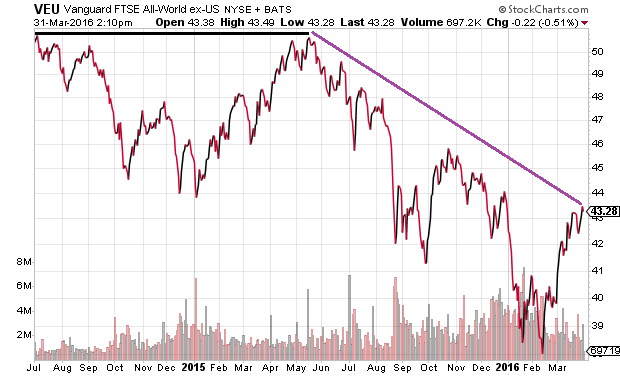

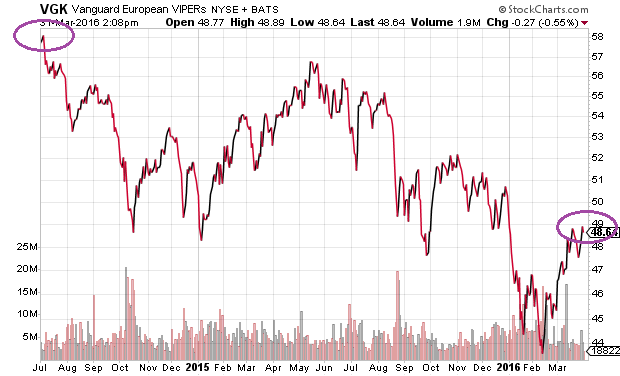

Everything comes back to the dollar’s epic ascent in the 3rd quarter of 2014. Slumping sales. Slumping earnings. Even the top for non-U.S. equities.

Take a look at Vanguard FTSE All World ex US (NYSE:VEU). Between July 1, 2014 and May 21, 2015, the exchange-traded tracker plummeted and recovered. However, it was unable to claim higher ground. Worse yet, VEU has depreciated substantially since the S&P 500 set a record high in May of last year.

The effect becomes even more noticeable when we isolate a region like Vanguard FTSE Europe (NYSE:VGK) or a sovereign like the United Kingdom via iShares MSCI United Kingdom (NYSE:EWU). Whereas U.S. market highs can be traced back to ten-and-a-half months ago (May 21), VGK and EWU have never recovered their July 2014 glory.

A cynic might say, “Who cares if most of the world’s equities have been declining for 21 months?” After all, the S&P 500 is within a stone’s throw of recapturing its all-time record (2130) at 2060. Yet one of the reasons for the violent 14% correction of the S&P 500 in January through mid-February was the threat that the dollar would soar to new heights if the Federal Reserve kept its pledge to hike rates four times in 2016. It has since lowered the bar to two, and many believe they’d be lucky to get away with one.

Unfortunately, the Fed may be caught in a pickle. Former Dallas Fed president Richard Fisher acknowledges that the institution deliberately created a wealth effect by front-loading a rally in stocks and real estate. The problem with doing so? Wealth effects eventually reverse themselves on the back-end, and the back-end typically begins at valuation extremes.

Make no mistake about it. We are sitting on valuation extremes. Based on estimates of as-reported earnings for the S&P 500’s first quarter of 2016 ($89.4), the current price-to-earnings ratio is at 23. Even the non-GAAP, adjusted operating earnings ($100.6) is a lofty 20.5. And low interest rates alone are not a panacea for exorbitant valuation levels.

Business sales stagnation. Prolonged profit weakness. And an economy that has been growing at a much slower pace over the last six months (1% or less) – far more lethargic than the 2% growth since the end of the Great Recession? Central banks have the power to prop up asset prices. Nevertheless, asset price reflation can quickly shift to deflation, particularly when revenue and earnings subside.

Disclosure: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc, and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert web site. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationships.