Pippa Stevens via CNBC recently had some advice:

“Panic selling not only locks in losses, but also puts investors at risk for missing the market’s best days.

Looking at data going back to 1930, Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) found that if an investor missed the S&P 500′s 10 best days in each decade, total returns would be just 91%, significantly below the 14,962% return for investors who held steady through the downturns.”

But here was her key point, which ultimately invalidates her entire premise:“The firm noted this eye-popping stat while urging investors to ‘avoid panic selling,’ pointing out that the ‘best days generally follow the worst days for stocks.’”

Think about that for a moment.

“The best days generally follow the worst days.“

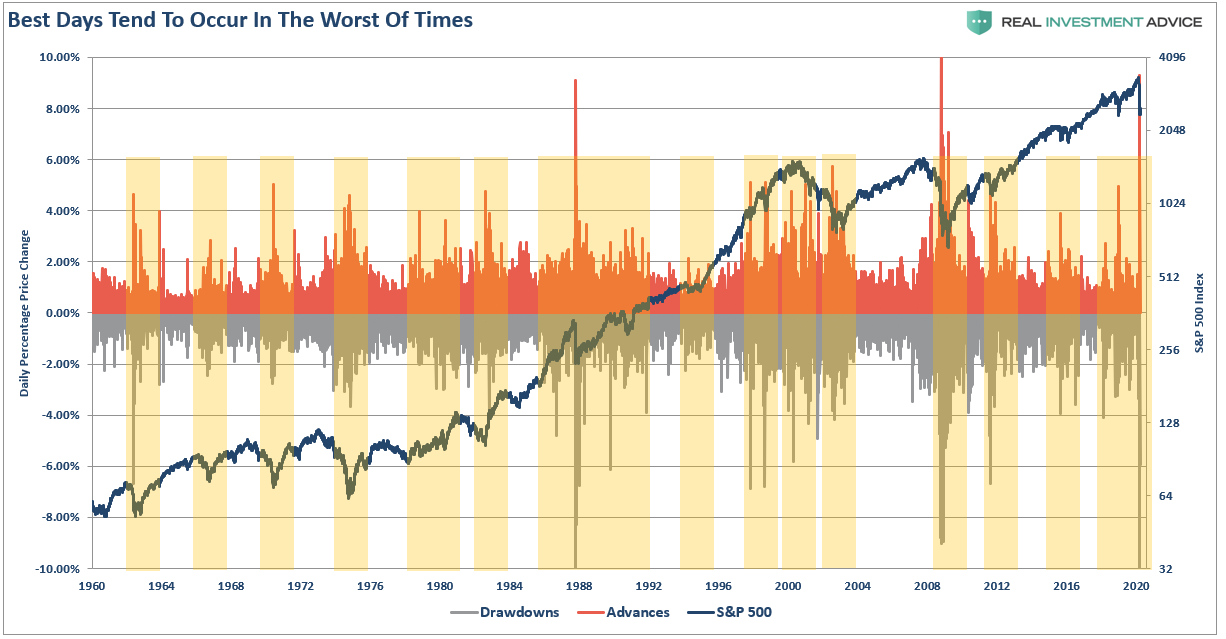

The statement is correct, as the S&P 500’s largest percentage gain days, tend to occur in clusters during the worst of times for investors.

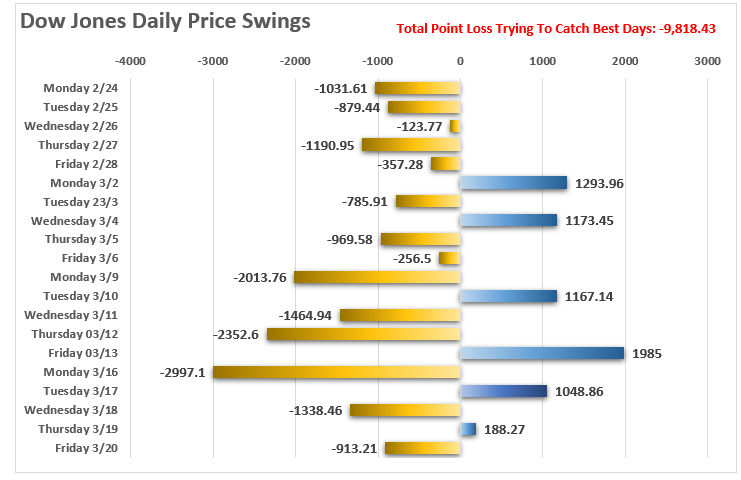

Here is another way to look at this through Wednesday's close. For an investor trying to catch the markets best 10-days, they wound up losing almost 30% of their portfolio, an astounding -9,254 points over the span of 3 weeks.

The analysis of “missing out on the 10-best days” of the market is steeped in the myth of the benefits of “buy and hold” investing. Buy and hold, as a strategy works great in a long-term rising bull market. It fails as a strategy during a bear market for one simple reason: Psychology.

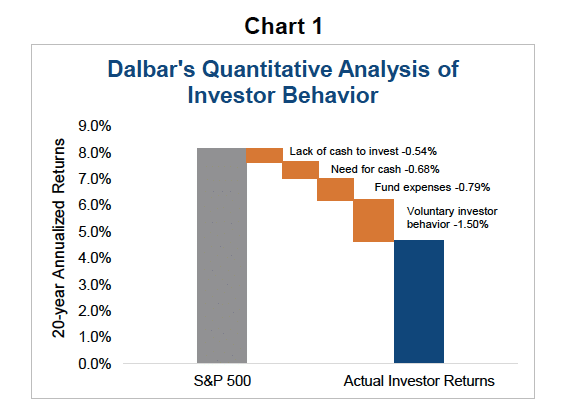

I absolutely agree investors should never “panic sell,” as such “emotional” decisions are always made at the worst possible times. As Dalbar regularly points out, individuals always underperform the benchmark index over time by allowing “behaviors” to interfere with their investment discipline.

In other words, investors regularly suffer from “buy high/sell low” syndrome.

Such is why investors should follow an investment discipline or strategy which mitigates volatility in order to avoid being put into a situation where “panic selling” becomes an issue.

Let me be clear, an investment disciple does NOT ensure your portfolio against losses if the market declines. This is particularly the case when it plummets as we’ve seen in the last couple of weeks. However, in any event, it will work to minimize the damage to a recoverable state.

The Market Timing Myth

We previously stated, that when the “crash” came, the mainstream media’s response would be: “Well, no one could have seen it coming.”

Simply always being “bullish,” like Mr. Santolli, is what leads investors into being blindsided by rising risks in the market.

Yes, you can see, and predict, when risks exceed the grasp of rationality.

This brings us to the basic argument from the financial media which is simply you are smart enough to manage your investments, so your only option is to “buy and hold.”

In 2010, Brett Arends wrote an excellent commentary entitled:“The Market Timing Myth” which primarily focused on several points we have made over the years. Brett really hits home with the following statement:

“For years, the investment industry has tried to scare clients into staying fully invested in the stock market at all times, no matter how high stocks go or what’s going on in the economy. ‘You can’t time the market,’ they warn. ‘Studies show that market timing doesn’t work.’

He goes on:

“They’ll cite studies showing that over the long-term investors made most of their money from just a handful of big one-day gains. In other words, if you miss those days, you’ll earn bupkis. And as no one can predict when those few, big jumps are going to occur, it’s best to stay fully invested at all times. So just give them your money… lie back, and think of the efficient market hypothesis. You’ll hear this in broker’s offices everywhere. And it sounds very compelling.

There’s just one problem. It’s hooey.

They’re leaving out more than half the story.

And what they’re not telling you makes a real difference to whether you should invest, when and how.”

The best long-term study relating to this topic was conducted a few years ago by Javier Estrada, a finance professor at the IESE Business School at the University of Navarra in Spain. To find out how important those few “big days” are, he looked at nearly a century’s worth of day-to-day moves on Wall Street and 14 other stock markets around the world, from England to Japan to Australia.

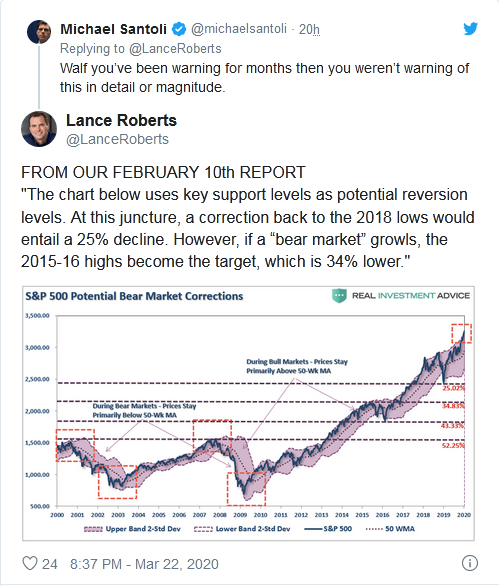

Correctly, the study did find that if you missed the 10-best days of the market, you did indeed give up much of the gains. What he also found is that by missing the 10-worst days, you did remarkably better.

(The blue highlight shows, as of Friday’s close, investors will need a more than 40% return just to get back to even.)

Clearly, avoiding major drawdowns in the market is key to long-term investment success. If I am not spending the bulk of my time making up previous losses in my portfolio, I spend more time compounding my invested dollars towards my long term goals.

Over an investing period of about 40 years, just missing the 10-best days would have cost you about half your capital gains. But successfully avoiding the 10-worst days would have had an even bigger positive impact on your portfolio. Someone who avoided the 10 biggest slumps would have ended up with two and a half times the capital gains of someone who simply stayed in all the time.

As Brett concluded:

“In other words, it’s something of a wash. The cost of being in the market just before a crash, are at least as great as being out of the market just before a big jump, and may be greater. Funny how the finance industry doesn’t bother to tell you that.”

The reason that the finance industry doesn’t tell you the other half of the story is because it is NOT PROFITABLE for them. The finance industry makes money when you are invested – not when you are in cash. Since a vast majority of financial advisors can’t actually successfully manage money, they just tell you to “stay the course.”

However, you DO have options.

A Simple Method

Now, let me clarify. I do not strictly endorse “market timing” which is specifically being “all-in” or “all-out” of the market at any given time. The problem with market timing is consistency.

You cannot, over the long term, effectively time the market. Being all in, or out, of the market will eventually put you on the wrong side of the ‘trade’ which will lead to a host of other problems.

However, there are also no great investors in history who employed “buy and hold” as an investment strategy. Even the great Warren Buffett occasionally sells investments. True investors buy when they see the value, and sell when value no longer exists.

While there are many sophisticated methods of handling risk within a portfolio, even using a basic method of price analysis, such as a moving average crossover, can be a valuable tool over the long term holding periods. Will such a method ALWAYS be right? Absolutely not. However, will such a method keep you from losing large amounts of capital? Absolutely.

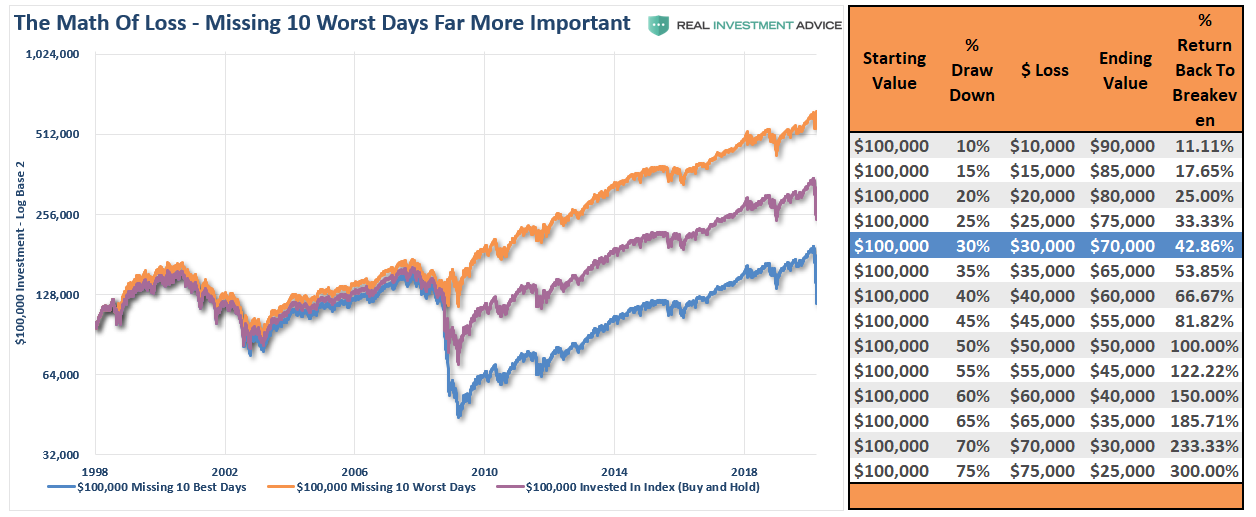

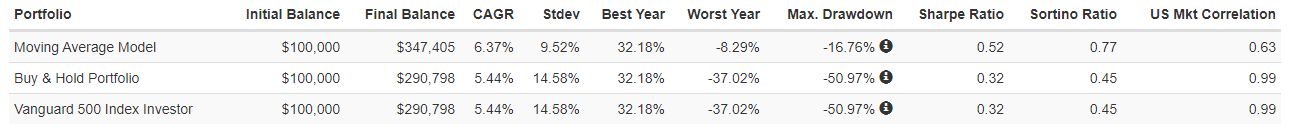

The chart below shows a simple 12-month moving average crossover study. (via Portfolio Visualizer)

What should be obvious is that using a basic form of price movement analysis can provide a useful identification of periods when portfolio risk should be REDUCED. Importantly, I did not say risk should be eliminated; just reduced.

Here are the comparative results.

Again, I am not implying, suggesting or stating that such signals mean going 100% to cash. What I am suggesting is that when “sell signals” are given that is the time when individuals should perform some basic portfolio risk management such as:

- Trim back winning positions to original portfolio weights: Investment Rule: Let Winners Run

- Sell positions that simply are not working (if the position was not working in a rising market, it likely won’t in a declining market.) Investment Rule: Cut Losers Short

- Hold the cash raised from these activities until the next buying opportunity occurs. Investment Rule: Buy Low

By using some measures, fundamental or technical, to reduce portfolio risk by taking profits as prices/valuations rise, or vice versa, the long-term results of avoiding periods of severe capital loss will outweigh missed short term gains.

Small adjustments can have a significant impact over the long run.

As Brett continues:

Let’s be clear what it doesn’t mean. It still doesn’t mean you should try to ‘time’ the market day to day. Mr. Estrada’s conclusion is that a small number of big days, in both directions, account for most of the stock market’s price performance. Trying to catch the 10 biggest jumps, or avoid the 10 big tumbles, is almost certainly a fool’s errand. Hardly anyone can do this sort of thing successfully. Even most professionals can’t.

But, second, it does mean you that you shouldn’t let scare stories dominate your approach to investing. Don’t let yourself be bullied. Least of all by someone who isn’t telling you the full story.”

There is little point in trying to catch each twist and turn of the market. But that also doesn’t mean you simply have to be passive and let it wash all over you. It may not be possible to “time” the market, but it is possible to reach intelligent conclusions about whether the market offers good value for investors.

There is a clear advantage of providing risk management to portfolios over time. The problem, as I have discussed many times previously, is that most individuals cannot manage their own money because of “short-termism.”

Despite their inherent belief that they are long-term investors, they are consistently swept up in the short-term movements of the market. Of course, with the media and Wall Street pushing the “you are missing it” mantra as the market rises – who can really blame the average investor “panic” buying market tops, and selling out at market bottoms.

Yet, despite two major bear market declines, and working its third, it never ceases to amaze me that investors still believe they can invest their savings into a risk-based market, without suffering the eventual consequences of risk itself.

Despite being a totally unrealistic objective, this “fantasy” leads to excessive speculation in portfolios which ultimately results in catastrophic losses. Aligning expectations with reality is the key to building a successful portfolio. Implementing a strong investment discipline, and applying risk management, is what leads to the achievement of those expectations.