In its 57-year history, the S&P 500 Index has become the center of the investment universe. In many cases, investors would be wise to resist its gravitational pull. The index has become the default mechanism for gauging market performance. Its ubiquity has also caused many investors and investment professionals to mistakenly apply the index as a mental benchmark for relative performance, even though the strategy it is compared with may invest in entirely different markets or securities.

The reasons for quick, default comparisons date back to our brain’s evolution. Financial markets are complex, and a growing number of asset classes and strategies within a portfolio make understanding (and coalescing) performance all-the-more difficult. To navigate complexity, our brain instinctually seeks “cognitive ease,” and reverts to heuristics, or well-known reference points to guide thinking. For investors, this means summing up relative performance of any element within a portfolio by simply asking “how did it compare to the S&P 500?”

This is particularly true for less experienced or knowledgeable investors who may meet with their financial advisor only a few times a year. But even some sophisticated investors who know a particular investment strategy may have a different benchmark (and ultimately use that appropriate benchmark for measuring relative performance), can’t help but ask how a strategy did against the go-to index.

While comparing performance to the S&P 500 is easy, investors should limit those comparisons to the select strategies that use it as their stated benchmark. This is particularly true today, when the S&P 500 is on a divergent path from many global indices. Below, are four reasons investors should avoid such faulty comparisons. They serve as reminders to keep performance comparisons realistic and on track.

1. Think Globally, Compare Locally

Even though the largest companies have a global footprint, U.S.-based companies are still tied closest to the domestic economy, and international companies tied closest to the economies of their respective host countries or regions. And the economic backdrop within these countries can vary considerably.

Presently, the U.S. economy has been growing at a more robust clip than Europe or many other parts of the world. Japan was previously an economic powerhouse, and emerging markets have experienced bouts of much stronger growth than the developed world. Given the varied economic environments, performance for domestic and international stock indices can differ considerably. Comparing an international fund or strategy to the S&P 500 makes little sense when the U.S. economy is stronger or weaker than other parts of the world. The more relevant question is whether that international fund is performing well relative to an international benchmark that is also tied to similar overseas economies.

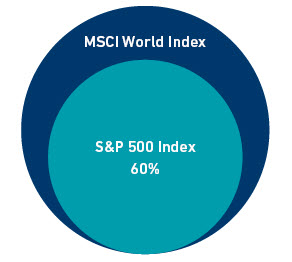

While allocators and investors frequently distinguish between international and U.S. benchmarks, they more often compare combined global strategies to the S&P 500. This is because there is more overlap between the U.S. and global stock indices. For example, the stocks in the S&P 500 are a subset of the MSCI World Index, making up approximately 60% of the weighting. That still leaves a lot of room for differences, however, as the diagram to the left shows.

2. Currency Differences Count A Lot

Currency fluctuations also have a big impact on the performance of different indices. This has been particularly true in the past year, as the Federal Reserve has gradually raised interest rates and the U.S. dollar strengthened against most currencies.

The table below displays the performance of the MSCI World Index in both U.S. dollars and the performance in local currencies. For the one-year period ending Jan. 31, the MSCI World Index in local currency lost -7.38%, but losses were steeper after currency translation with the MSCI World USD losing -8.71%. A significant portion of the index’s loss (in dollar terms) was due to currency effects.

Annual Performance (%)

| Year | MSCI World (USD) | MSCI World (Local) | S&P 500 |

| 2018 | -8.71 | -7.38 | -4.38 |

| 2017 | 22.40 | 18.48 | 21.83 |

| 2016 | 7.51 | 9.00 | 11.96 |

| 2015 | -0.87 | 2.08 | 1.38 |

| 2014 | 4.94 | 9.81 | 13.69 |

| 2013 | 26.68 | 28.87 | 32.39 |

| 2012 | 15.83 | 15.71 | 16.00 |

| 2011 | -5.54 | -5.49 | 2.11 |

| 2010 | 11.76 | 10.01 | 15.06 |

| 2009 | 29.99 | 25.73 | 26.46 |

| 2008 | -40.71 | -38.69 | -37.00 |

| 2007 | 9.04 | 4.69 | 5.49 |

| 2006 | 20.07 | 15.55 | 15.80 |

| 2005 | 9.49 | 15.77 | 4.91 |

Source: MSCI and S&P

3. Investment Styles Go In And Out Of Favor, Causing Varied Index Performance

Another factor making it dangerous to compare the wrong index is the varied performance of different investment styles. Growth stocks have outperformed value stocks considerably in recent years. The S&P 500 includes both value and growth stocks. If one inappropriately used the S&P to evaluate a growth fund’s performance, the growth fund would look exceptional. Conversely, if one were to use the index to evaluate a value manager’s relative performance, that manager’s performance would look poor due to the growth-oriented stocks in the S&P 500.

Growth of $100

Growth vs. Value

Source: S&P 2008-2018

4. Using The Wrong Benchmark Undermines The Basic Tenets Of Modern Portfolio Theory

Above all, a fixation on the S&P 500 subconsciously chips away at the foundation of modern portfolio theory. For decades, financial theory has espoused diversification to create efficient portfolios that maximize returns for a given level of risk. Different asset classes under- and outperform at different times, creating a steadier return profile. The investment community at large spends countless hours and resources teaching new investors about the benefits of portfolio diversification. Comparing a portfolio to the wrong benchmark may serve our interests when it comes to cognitive ease but undermines those important lessons.

Conclusion: While the S&P 500 can be a quick barometer for U.S. equity market performance, allocators and investors should avoid comparing strategies to the popular index when it is not the stated benchmark. The comparison can be particularly misleading in the current market climate, given the divergent paths of the U.S. and international economies, the disparity between growth and value performance and wide currency fluctuations. Beyond these near-term differences, faulty benchmark comparisons undermine the long-term value of portfolio diversification. This basic investment principle is one the investment community should strive to preserve.