The US stock market entered a complacent phase after our post-Brexit entry. Although we benefited significantly from being contrarians and buying the dip immediately after the UK referendum, we were cautious about underlying conditions and monitored the market closely during the summer months. Low trading volume was likely a contributor to the less-than-1% range of market daily movement for more than 40 consecutive sessions. But we viewed the two-month-long period of low volatility as the calm before the storm. Whether the cause was fear of a September rate hike or investors harvesting profit, on September 9 the stock market experienced its biggest falloff since the Brexit vote.

Buy The Dips?

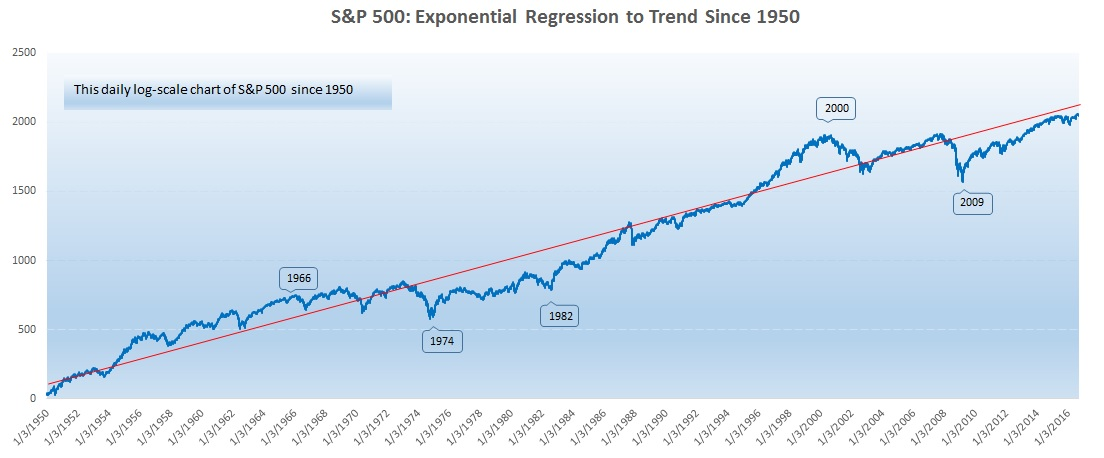

As contrarians, we are often asked by our clients and friends if they should buy market dips. While we cannot recommend catching every falling knife, there are well-documented benefits from being a contrarian. One persistent market anomaly is the price momentum, demonstrated by the positive auto-correlation in stock returns. However, drastic short-term movements can cause deep momentum and market overreaction. As research in the 1980s and ’90s showed, a portfolio that sells “winners” and buys “losers” can produce positive returns. This pattern is also important in cross-sectional auto-correlations. For a better understanding of the argument, we can refer to the market’s long-run movement in the following chart.

As we see in Figure 1, the stock market is on a long-term upward trend correlated with economic development. However, there are sometimes violent downward drags, which technicians refer to as corrections. Although the duration of each overreaction varies, regression to the long-term mean of the market eventually brings price adjustments to the upside. A typical contrarian strategy is to identify these overreactions and profit from the mean reversal process.

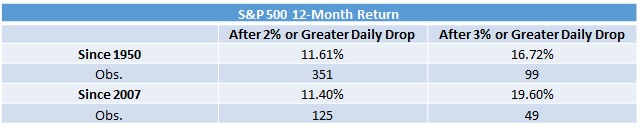

So when is the best time to buy the market dip? While there are numerous methods, one rule of thumb never ceases to amaze: the harder you fall, the higher you bounce. Table 1 summarizes 12-month returns following radical one-day downturns in the S&P 500. Since 1950, the market has averaged an 11.6% one-year return after a 2% or greater daily change and a 16.7% return following a one-day drop of 3% or more. The effect has been even more pronounced in the past decade, but not driven by the crisis period.

Investors should not expect the market to behave in a monotonic fashion. Don’t be afraid to be different.