Looking at the 10/31/22 return data for the major indices, what struck me this morning was that the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (NYSE:AGG) is down almost as much as the S&P 500 year to date (ytd). It’s not quite there, but given the proximity in negative returns, it was still surprising since the worst year for the bond market(s) prior to 2022, was 1994 and I thought the AGG wound up finishing 1994 down roughly 2%.

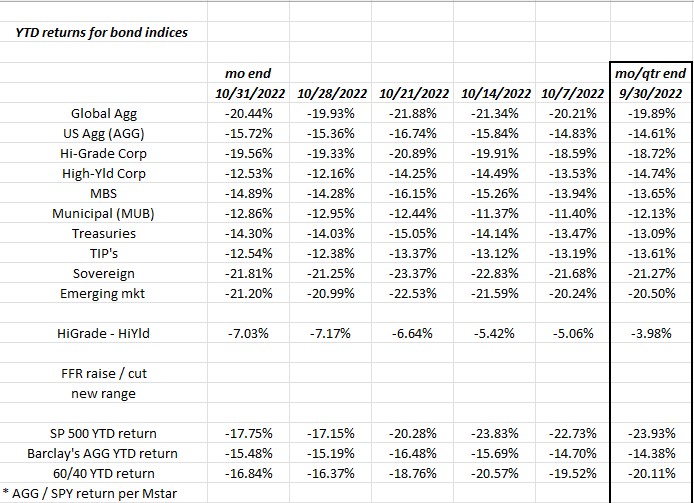

10/31/2022 Year To Date returns:

- SPY: -17.75%

- AGG: -15.48%

- 60/40: -16.84%

YTD returns across major bond asset classes:

Here’s a table that was started in March – April 2020 in the depths of the pandemic to force me to track the various returns across fixed-income asset classes. This data is put out by Bloomberg every day and it’s usually updated weekly and then again at month end. Morningstar gives very good return data, but for practical purposes it’s just easier to track the Bloomberg data.

However readers should note the line “HiGrade – HiYield” on the spreadsheet. For some bizarre reason I started tracking the difference in returns during the pandemic and as of 10/31/22, the ytd return on high yield is far better than the return on corporate high-grade, and most readers are astute enough to attribute this to the duration on high-grade and intermediate bond funds versus the duration on high-yield ETFs and high-yield bond funds.

At the end of 2020, after the 10-year Treasury printed a 55 basis point yield-to-maturity (ytm) in late August, 2020, I thought I read the duration on your average intermediate or investment-grade bond fund was between 9 – 10 years, while the duration on your average high-yield fund was still around 6 years.

The point is, for readers, that high-grade or investment-grade corporates are looking cheap with average spreads between 150 – 175 basis points (bp) over equivalent Treasuries, while high-yield corporate has traded well in the second half of 2022, and has not traded below it’s June 2022 lows.

How has the Treasury curve behaved since June 30 2022?

1-year Treasury yield change:

- rose 18 bp to 2.98% in July 2022;

- rose 54 bp to 3.52% in August 2022;

- rose 53 bp to 4.05% in September 2022;

- rose 70 bp to 4.75% in October 2022;

2-year Treasury yield change:

- fell 3 bp to 2.89% in July 2022

- rose 61 bp to 3.50% in August 2022

- rose 72 bp to 4.22% in September 2022

- rose 29 bp to 4.51% in October 2022

5-year Treasury yield change:

- fell 31 bp to 2.70% in July 2022

- rose 75 bp to 3.45% in Aug 2022

- rose 61 bp to 4.06% in Sept 2022

- rose 21 bp to 4.27% in Oct 2022

Readers can see that August and September 2022 were significant curve-flattening in the front of the curve and then once that eased both in July and October 2022, the S&P rallied.

Do we repeat this Treasury action now in November and December 2022? The change in yields and Powell’s comments after the FOMC announcement today will be a good indicator.

Conclusion

@NickTimaraos is the Wall Street Journal reporter that’s otherwise known as the “Fed Whisperer” i.e. he seems to have the inside track on what policy changes the Fed is contemplating, and how they are leaning. It appears that 75 bp is baked in to today’s announcement, which would leave the fed funds rate at a mid-range of 3.875% and then the Fed is expected to do 50 bp in December 2022 and then 25 bp at the two meetings after that.

And this is all data dependent and it’s still just a guess.

Remember in 2018, Jay Powell stayed hard on the brakes through December 2018 and then the S&P and the US equity markets reversed course in the last week of the year and that turned out to be the turning point for both the markets and monetary policy.

However, in 2022, inflation still hasn’t capitulated, and that’s a problem.

So far, nothing has really changed although the pundits still talk about “Fed pivots” and other reasons for Powell to back off the fad funds rate increases.

However, there is relative value being created in the various bond market asset classes. Sovereign debt and Emerging Market bond asset classes are down 20% in 2022, and this was after years of zero rates. Client’s don’t own either asset class in any size, but a change in the dollar’s strength would have me watching the price reaction(s).

A more rapid deterioration in the economic data – such as a bad Friday October payrolls number – would certainly drive interest in the 10-year Treasury and even high-grade bond ETF’s or funds, although economic deterioration that is too rapid, will cause further spread-widening in high-grade corporates.

Something will give at some point. Something will break to change the bond market’s direction.

Be patient.