The average economic expansion since the 1940s is roughly five years. The current recovery? We are now at the six-year mark. Yet there’s a problem with today's environment that few are willing to talk about; that is, historically, the Federal Reserve raises overnight lending rates to slow economic growth and suppress inflationary tensions. This time around, however, the U.S. economy is already growing at a lethargic pace and inflation is negligible.

How does one reconcile the notion that there is no need to curb economic growth or subdue inflationary pressure with the Fed’s intent to raise borrowing costs? Some believe that committee members wish to deflate asset prices before they get out of hand. By most valuation measures, though, prices are already distorted. Others explain that the Fed is not really tightening borrowing costs, but rather, transitioning from ultra-easy monetary policy to extremely easy monetary policy. This explanation amounts to little more than word play.

Perhaps there is a more legitimate justification for why the central bank hopes to begin a series of modest rate hikes in 2015. Could it be that the Fed needs to provide itself with greater firepower before the onset of the next recession? Again, the time horizon for the current recovery is already longer than the typical expansionary period. It follows that if the Fed fails to leave the 0% level in 2015, it would find itself introducing a fourth iteration of quantitative easing (QE4) without ever having claimed a higher ground first.

The Fed’s prayers notwithstanding, we may not see meaningfully higher borrowing costs for decades to come. Consider Japan’s quandary. Its central bank, the Bank of Japan (BOJ), has attempted to stimulate its humdrum economy for 15 years, employing unconventional asset purchases as well as ultra-low lending rates. Today, the BOJ’s overnight “call” rate is at the 0% level. The BOJ’s highest overnight rate this century? A paltry 0.5%.

Granted, the U.S. may not be as dependent on exports as Japan. And the Japanese people are bigger savers than we are. Nevertheless, why would anyone expect the Fed to push rates to meaningfully higher levels? Even if the Fed managed to get rates up to 1% by the end of 2016 – even if overnight borrowing costs peaked at 1.5% in 2017 – wouldn’t rates head back down to the “zero bound” when the next recession arrives? Recognizing the history of economic cycles, we are closer to the end of the expansion than the beginning of it.

There are two instances (1948, 1980) when the U.S. economy had been growing at a sub-par clip and the Fed acted to raise its target lending rate. In both cases, a new recession occurred in less than a year’s time. Put another way, if the Fed lifts its rate target in 2015, one should anticipate an exceptionally high likelihood of economic contraction in 2016.

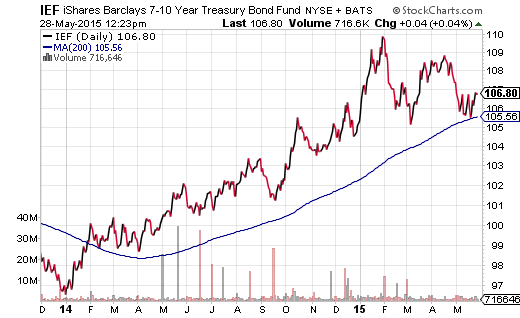

There are several implications for market-based asset classes. First, intermediate-term treasuries still provide safety in progressively uncertain economic surroundings. The Fed can talk about pushing borrowing costs up marginally; journalists can squawk about rising bond yields. In reality, however, the 10-year yield at 2.14% is approximately where it began the year and the iShares 7-10 Year Treasury (ARCA:IEF) remains in a long-term technical uptrend.

One might also want to remember that the 2.14% yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury note is a far better value than the Japanese 10-year at 0.40% or the German 10-year at 0.53%. Why wouldn’t foreign dollars flow into U.S. sovereign debt that represents a substantially higher yield at equivalent quality? Add to the equation that U.S. government obligations come in U.S. dollars that are likely to rise in value or maintain their value against the yen or the euro going forward.

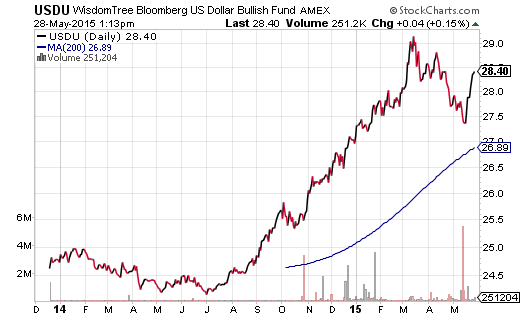

Second, safer-haven currencies like the dollar and the Swiss franc still have the wind at their back. Specifically, virtually all of the world’s central banks are aggressively easing borrowing costs and/or seeking to devalue. The yen continues to hit new multi-year lows; the euro is within shouting distance from revisiting its bottom in March. While it is true that most of the damage to currencies across the globe may already be “priced in” – while it is likely that financial markets anticipated dollar and franc strength in advance of present-day government actions – the greenback still gets the nod during periods of economic uncertainty. Other than “carry trade” reversals when those who borrowed the euro to invest in U.S. assets are forced to repay those loans, investing in the dollar remains fundamentally and technically sensible. PowerShares Dollar Bullish (NYSE:UUP) and WisdomTree Dollar Bullish (USDU) should be a consideration as long as the respective up-trends hold.

Third, and perhaps most critically, what can investors expect from stock assets in the weeks and months ahead? A whole lot of sideways movement. The tailwinds? Stock buybacks and dividends remain a robust area of support; strong technical uptrends are in force and economic uncertainty may push the Fed’s plans for lift-off further out into the future. Unfortunately, the headwinds are equally venerable. Nearly every valuation metric in existence indicate over-inflated pricing. Corporate profitability has been waning, sales have been stalling and complacency is festering. One study demonstrated that the year-to-date trading range for the Dow Jones Industrials is the 4th lowest in 115 years.

It follows that client stock exposure has not changed much since January 1. Long-time readers recognize the list of many of our top positions including, but not necessarily limited to: iShares S&P 100 (NYSE:OEF), SPDR Select Health Care (ARCA:XLV), PureFunds ISE CyberSecurity ETF (HACK), iShares USA Minimum Volatility (NYSE:USMV), iShares MSCI Currency Hedged EAFE (HEFA) and Vanguard Europe Pacific (NYSE:VEA). We also maintain an average client cash level of 10%-15% for opportunistic purchases in the next meaningful market pullback.