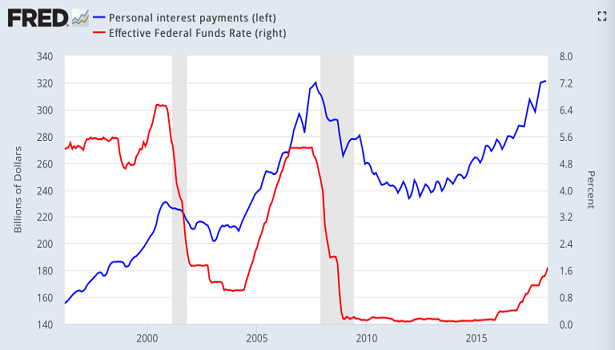

Mortgage interest payments as well as non-mortgage interest payments are costing consumers more and more of their disposable income. Consider the non-mortgage variety. Personal-interest payments have already recovered levels not seen since the financial crisis.

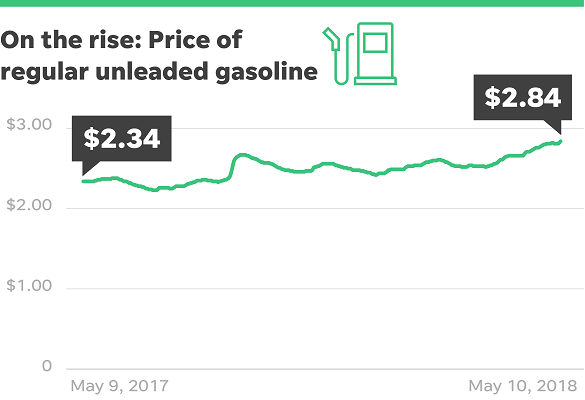

To be sure, interest payments are not the only thing taking a bite out of the cost of living. Oil prices have moved meaningfully higher. According to a 2005 study by the Federal Reserve, oil-price increases adversely affect aggregate consumer spending.

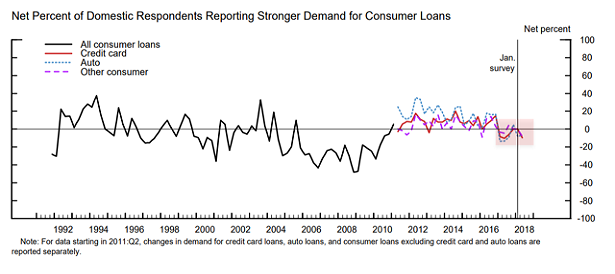

Is it possible that consumers will ratchet up borrowing to keep up the brisk pace of consumption? Perhaps. Yet loan growth is not only slowing, it’s rolling over.

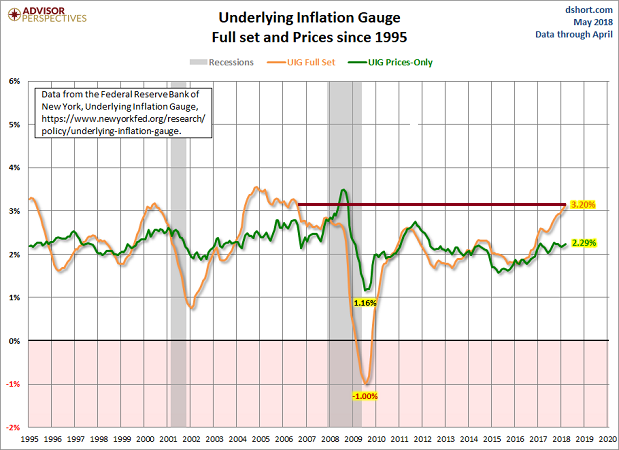

Granted, recent tax cuts place more dollars in the pockets of Americans. Higher wages do the same. On the flip side, there is plenty of evidence to show that inflation is eroding the purchasing power of those dollars.

For example, the New York Fed’s Underlying Inflation Gauge (UIG) hit 3.2% in April. UIG has not been this high since the summer of 2006.

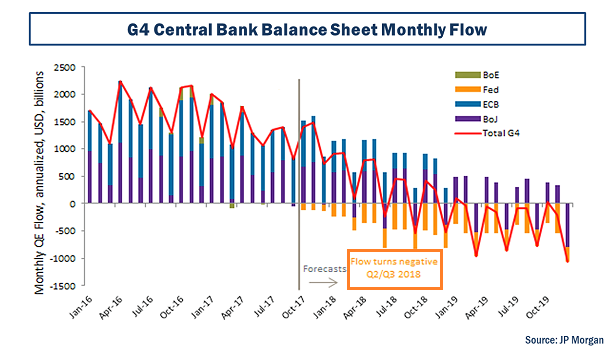

When Federal Reserve monetary policy is stimulative, it may be reasonable to ignore signs of economic wear and tear. Right now, however, the Fed is doggedly determined to push borrowing costs higher. The central bank of the United States is simultaneously raising its overnight lending rate and reducing its balance sheet via quantitative tightening (QT).

If central banks around the world were electronically creating credits to buy assets (a.k.a. “quantitative easing” or “QE”) at the same rate as they had in the past, then tightening stateside might not be so precarious. Yet foreign central banks are slowing down their stimulus trains as well.

In fact, developed market central banks shifted from an annualized pace of $2 trillion in monetary support in Q2 of 2016 down to roughly $1 trillion by October of 2017. By July of 2018, monthly monetary support will likely turn negative.

Will our stimulus addicted world actually be able to stand on its own? We are about to find out.

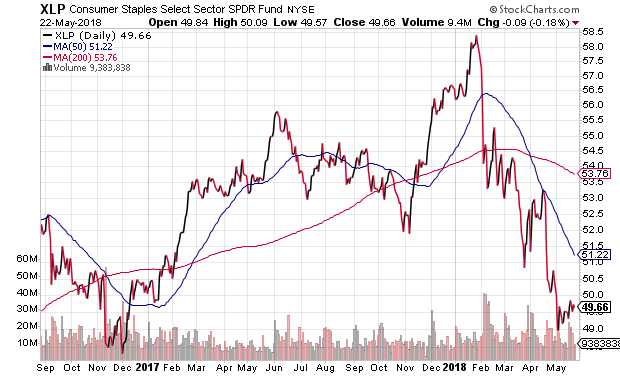

One way or another, investors are starting to recognize that stocks and higher-yielding bonds are risk-bearing assets. Not only is the emergence of a premium for risk visiting center stage, but market participants are reacquainting themselves with alternatives.

For instance, many are currently questioning dividend yields of 3% in exchange-traded funds like SPDR Select Sector Consumer Staples (NYSE:XLP) and/or 3.5% in exchange-traded funds like SPDR Select Sector Utilities (NYSE:XLU). After all, safer cash equivalents yield as much as 2% in exchange-traded funds like Pimco Enhanced Short Maturity Active (NYSE:MINT).

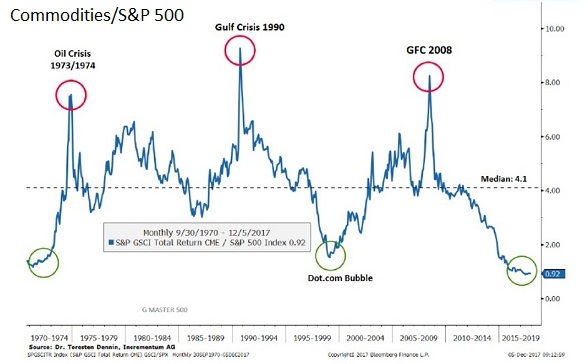

Similarly, risk assets that had previously been out of favor may become more desirable. The iPath Bloomberg Commodity Index Total Return ETN (NYSE:DJP) just notched a fresh 52-week high, even as the dollar continues to strengthen.

And why not? The relative attractiveness of commodities over the S&P 500 is difficult to refute.

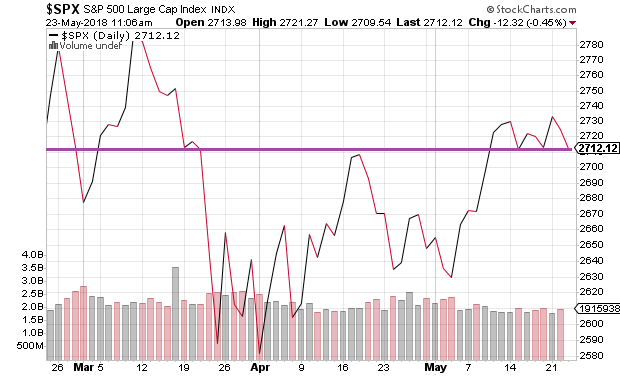

“Wait just one minute there,” you protest. “Aren’t forward earnings-per-share estimates in the area of 20%?” Why yes, they are. Yet the S&P 500 failed to make meaningful progress in the tax-cut-inspired earnings season.

So stocks barely benefited from one of the strongest showings for earnings in this century. Heck, it was one of the best performances on first quarter results and on forward guidance ever. Yet the best the stock market could do was hold its ground?

There is a primary reason for underwhelming price movement in equities today. Consider the reality that when traditional easing and QE force borrowing costs into the basement, every aspect of society (e.g., households, corporations, governments, etc.) borrows a whole lot of “dough.” On the flip side, when traditional tightening and QT push borrowing costs higher, some borrow less and others borrow at higher interest rates. Either way, the massive debt that helped to lever up asset prices begins to leave asset prices susceptible.

It’s not that one should abandon all exposure to risk assets or to stocks. Nevertheless, the notion that there is no alternative (T.I.N.A.) to equities can be tossed out of a single casement window. Cash equivalents provide value for the near term. Commodities may provide value over the next 10-year period. Even investment-grade convertible bonds with 6% yield-to-maturities are likely to outperform equities with less risk.

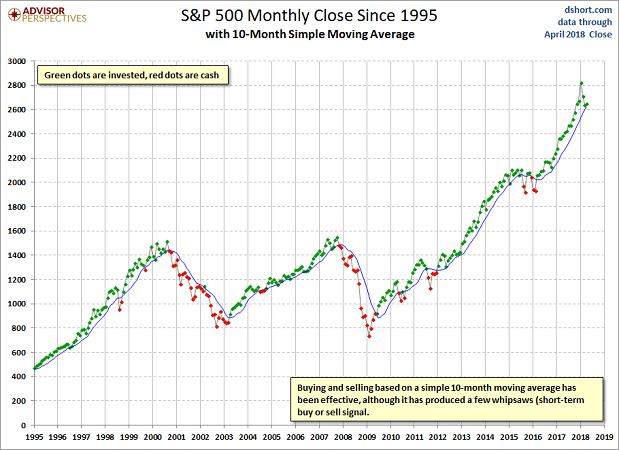

In spite of mounting evidence that stocks will have a rough go of it over the next three years, we still maintain a healthy allocation for our near-retiree and retiree client base. The reason? We have a time-tested exit strategy. When the MONTHLY close of the 10-month moving average falls below its trendline, we significantly reduce our stock market footprint.