The inability of the crowd to earn anything close to Mr. Market’s performance is a hardy perennial. Although replicating market betas via low-cost index products has become child’s play, the persistent failure by most investors on this front is striking, as a recent study by Dalbar reminds.

The consultancy’s current annual study of how investor results stack up vs. markets is shocking, but it remains shocking year after year. Analyzing data for mutual funds and market benchmarks, Dalbar’s “23rd Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior”, which reviews returns through the end of 2016, is a recurring study of how individuals generally are their own worst enemy when it comes to earning healthy returns.

“No matter what the state of the mutual fund industry, boom or bust,” Dalbar advises, “investment results are more dependent on investor behavior than on fund performance. Mutual fund investors who hold on to their investments have been more successful than those who try to time the market.”

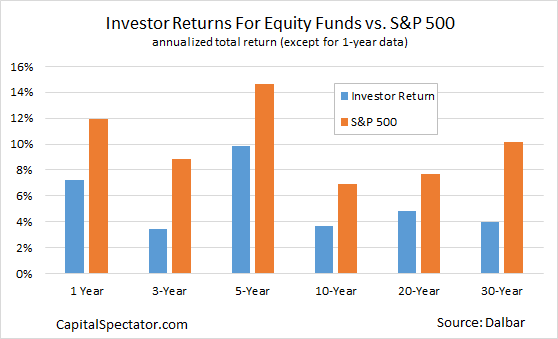

Consider how the average equity fund investor has fared against the S&P 500 Index. For the trailing ten-year period through last year’s close, for instance, the US stock market earned an annualized 6.95%, or nearly double the investor return of 3.64%. Hefty gaps for other time periods are the norm as well, as the chart below shows.

The difference is especially striking over the trailing 30-year period: The average equity investor earned a hair below 4.0% a year while the S&P deliver a bit more than 10%.

The numbers aren’t any better for bonds. Measuring investor returns for fixed-income funds vs. the Bloomberg Barclays (LON:BARC) Aggregate Bond Index also reveals a dramatic mismatch in favor of the benchmark. For the past decade through the end of last year, for instance, the bond index was ahead by an annual 3.97%, a huge edge over the weak 0.40% earned by the average fund investor.

“Investors so often cost themselves money because the behaviors elicited by short-term focus are almost always irrational,” the Dalbar study explains. “While many investors set a course of action that is based on a well-planned rationale and considers the full time horizon, those plans can take a back seat when fear or exuberance sets in.”

Perhaps the most compelling lesson in the data is that investors are in desperate need of informed investment counsel. Although some folks are earning reasonable, perhaps stellar, returns, the vast majority are wallowing in various degrees of subpar results.

The real tragedy is that satisfactory returns are easily obtained with simple asset allocation strategies via index funds. The inability of most investors to exploit these opportunities speaks volumes about how the human mind works when it comes to finance.

The good news is that the crowd’s failure lays the foundation for alluring possibilities for the elite. Consider, for instance, opportunistic rebalancing strategies that focus on adjusting a portfolio’s asset mix based on changes in expected return. The natural inclination for most market participants is to sell when ex ante performance rises (i.e., prices decline) and buy when ex ante return falls (prices rise). This may be rational if you’re managing a short-term momentum-based strategy with a tightly controlled risk-management process. But for investors with longer-term horizons it’s a recipe for disaster, as the Dalbar data shows.

Taking a more philosophical view suggests that there’s nothing unusual here and that the results are merely part of the natural order of finance. Recall that Professor Bill Sharpe advised that the search for alpha is a zero sum game. “Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs,” he wrote.

If you think of any advantages for portfolios (higher return and/or lower risk) via rebalancing vs. an unmanaged bencharmk as alpha, a Sharpe-inspired view of strategy results implies that the ability to enhance risk-adjusted performance faces capacity limits. In short, there’s only so much rebalancing-related alpha to go around. To the extent that it exists at all, most of it (all of it?) is created by poor decisions via the majority of investors.

By that standard, a select group of investors will have no problem harvesting rebalancing-linked alpha for decades to come for a simple reason: The average investor shows little if any ability to learn from past mistakes.