Summary: The macro data from the past month continues to mostly point to positive growth. On balance, the evidence suggests the imminent onset of a recession is unlikely.

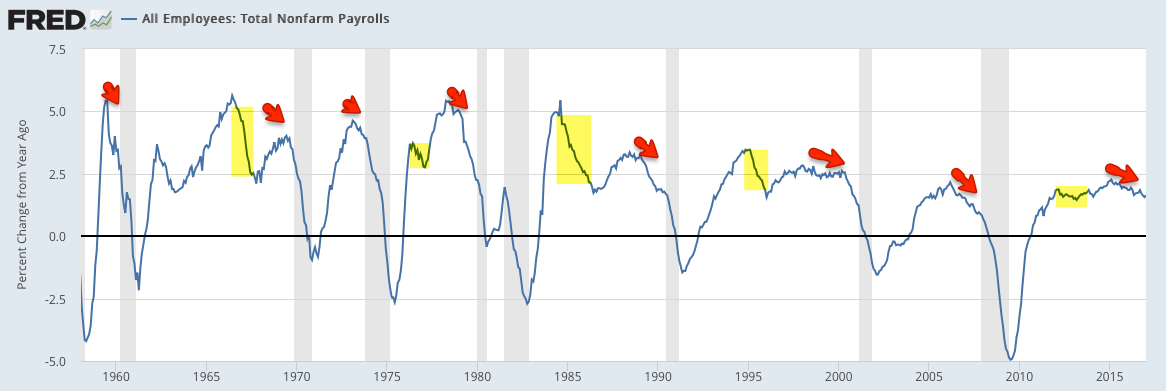

That said, there are some signs of weakness creeping into the data. Employment growth is decelerating, from over 2% last year to 1.6% now. Housing starts and permits have flattened over the past 1-2 years. There is nothing alarming in any of this but it is noteworthy that expansions weaken before they end, and these are signs of some weakening that bear monitoring closely.

Overall, the main positives from the recent data are in employment, consumption growth and housing:

- Monthly employment gains have averaged 195,000 during the past year, with annual growth of 1.6% yoy. Full-time employment is leading.

- Recent compensation growth is the highest in 7-1/2 years: 2.8% yoy in December, falling to 2.5% in January.

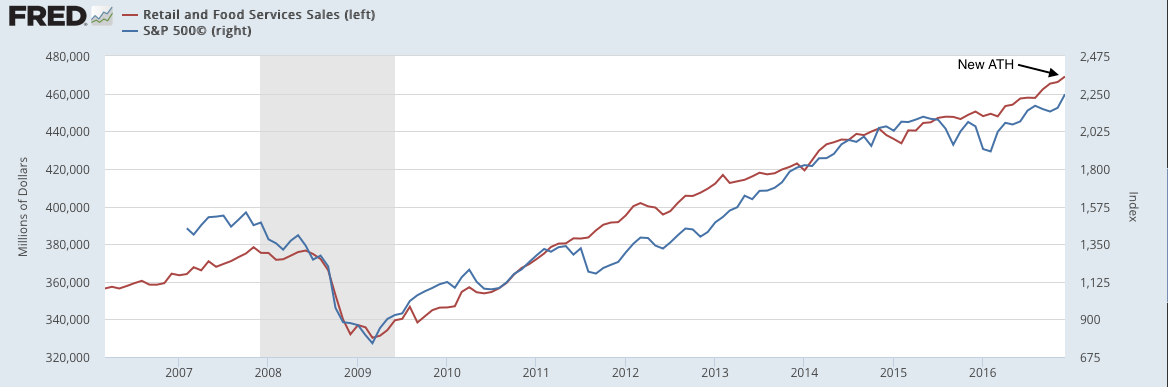

- Most measures of demand show 3-4% nominal growth. Real personal consumption growth in 4Q16 was 2.8%. Retail sales reached a new all-time high in December, growing 2.0% yoy.

- Housing sales grew 12% yoy in 2016. Starts made a new 9-year high in October.

- The core inflation rate has remained near 2% since November 2015.

The main negatives are concentrated in the manufacturing sector (which accounts for less than 10% of employment):

- Core durable goods growth rose 3.4% yoy in December, it's best growth since April 2015. It was weak during the winter of 2015 and is slowly rebounding in recent months.

- Industrial production has also been weak, rising by just 0.5% yoy due to weakness in mining (oil and coal). The manufacturing component grew 0.4% yoy.

Prior macro posts are here.

* * *

Our key message over the past 4 years has been that (a) growth is positive but slow, in the range of ~3-4% (nominal), and; (b) current growth is lower than in prior periods of economic expansion and a return to 1980s or 1990s style growth does not appear likely.

Modest growth should not be a surprise. This is the typical pattern in the years following a financial crisis like the one experienced in 2008-09.

This is germane to equity markets in that macro growth drives corporate revenue, profit expansion and valuation levels. The saying that "the stock market is not the economy" is true on a day to day or even month to month basis, but over time these two move together. When they diverge, it is normally a function of emotion, whether measured in valuation premiums/discounts or sentiment extremes (enlarge any image by clicking on it).

A valuable post on using macro data to improve trend following investment strategies can be found here.

Let's review each of these points in turn. We'll focus on four macro categories: labor market, inflation, end-demand and housing.

Employment and Wages

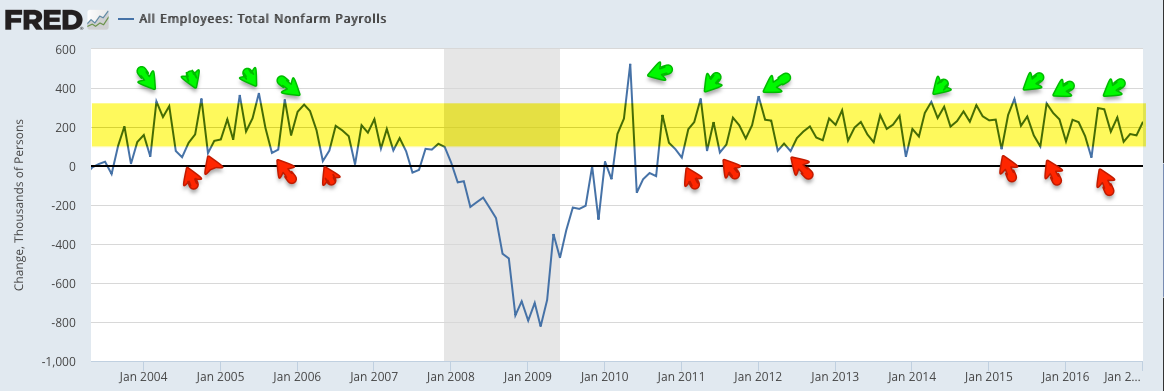

The January non-farm payroll was 227,000 new employees minus 39,000 in revisions.

In the past 12 months, the average monthly gain in employment was 195,000.

Monthly NFP prints are normally volatile. Since 2004, NFP prints near 300,000 have been followed by ones near or under 100,000. That has been a pattern during every bull market; NFP was negative in 1993, 1995, 1996 and 1997. The low prints of 84,000 in March 2015 and 24,000 in May 2016 fit the historical pattern. This is normal, not unusual or unexpected.

Why is there so much volatility? Leave aside the data collection, seasonal adjustment and weather issues; appreciate that a "beat" or a "miss" of 80,000 workers in a monthly NFP report is equal to just 0.05% of the US workforce.

For this reason, it's better to look at the trend; in January, trend employment growth was 1.6% yoy. Until last spring, annual growth had been over 2%, the highest since the 1990s. Ahead of a recession, employment growth will likely markedly fall (arrows). Continued deceleration in employment growth in the coming months is therefore a critical watch out.

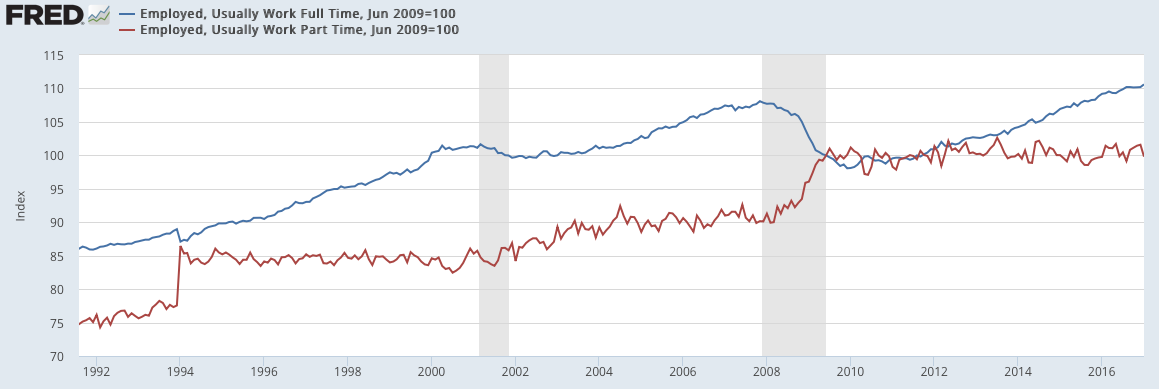

Employment has been been driven by full-time jobs, which are at a new all-time high (blue line), not part-time jobs (red line).

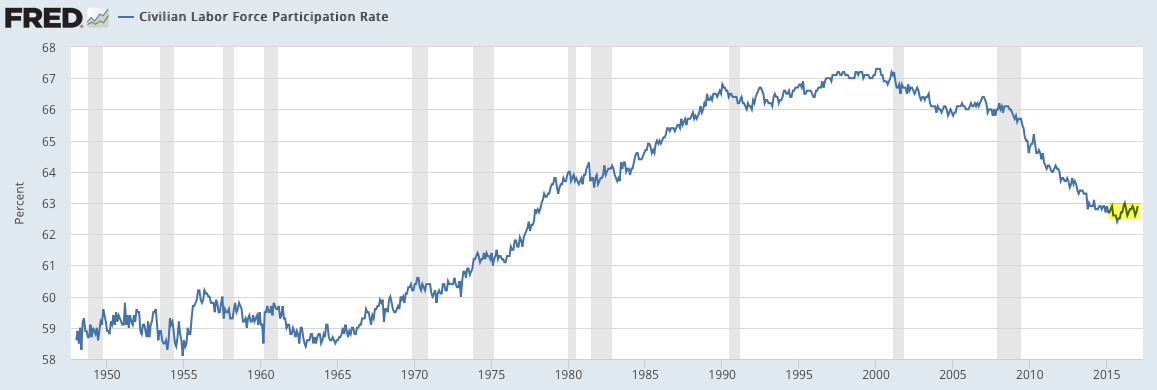

The labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population over 16 that is either working or looking for work) has been falling. This has little to do with the current recovery; the participation rate has been falling for more than 16 years. Participation is falling as baby boomers retire, exactly as participation started to rise in the mid-1960s as this group entered the workforce. Another driver is women, whose participation rate increased from about 30% in the 1950s to a peak of 60% in 1999.

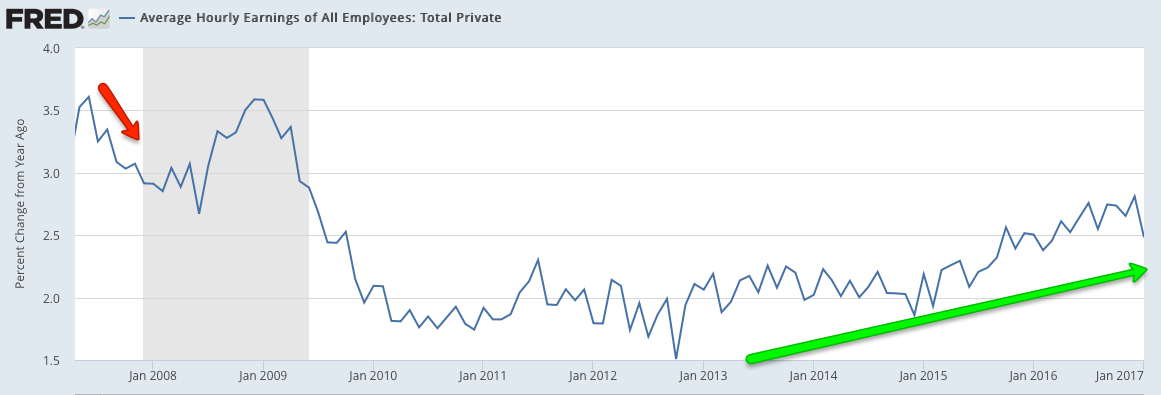

Average hourly earnings growth was 2.8% yoy in December, the highest growth rate in 7-1/2 years. That dropped to 2.5% in January. This is a positive trend, showing demand for more workers. Sustained acceleration in wages would be a big positive for consumption and investment that would further fuel employment.

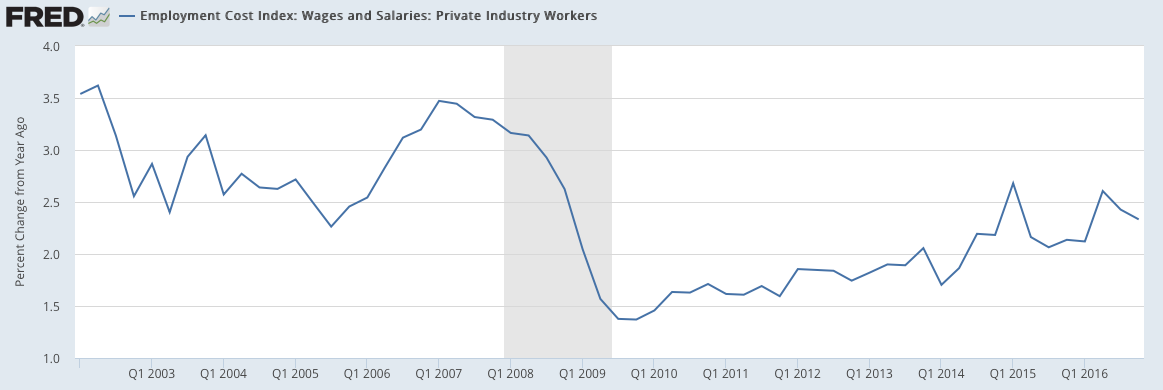

Similarly, 4Q16 employment cost index shows compensation growth was 2.3% yoy. This is near the highest growth rate since the recession.

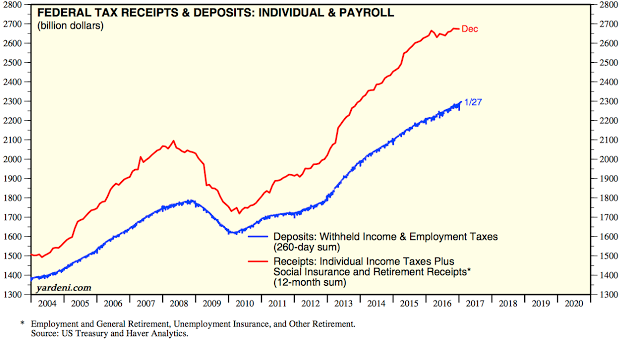

For those who doubt the accuracy of the BLS employment data, federal tax receipts have also been rising to a new high (red line), a sign of better employment and wages (from Yardeni).

Inflation

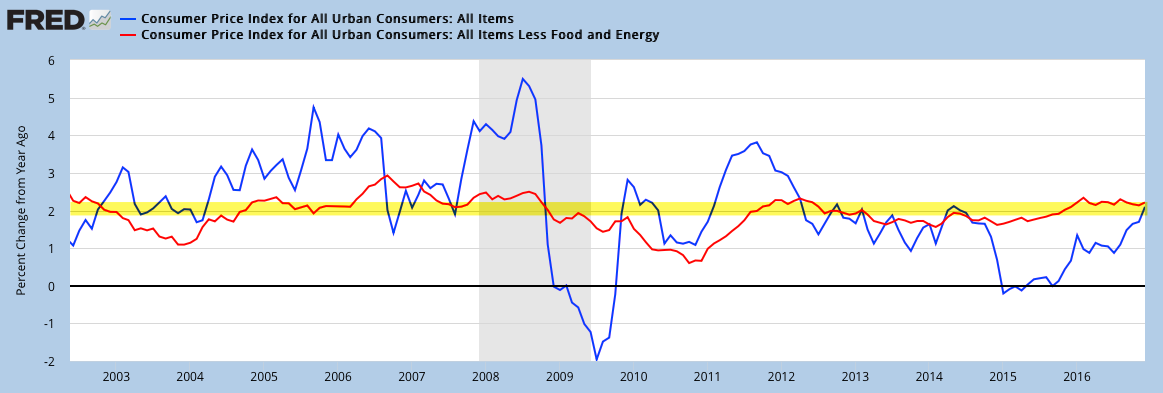

Despite steady employment growth, inflation remains stuck near the Fed's target of 2%. But note: CPI and PCE are finally ticking higher.

CPI (blue line) was 2.1% last month, the first time it has been over 2% since June 2014. The more important core CPI (excluding volatile food and energy; red line) grew 2.2%, among the highest levels since 2008 although still just oscillating near 2%.

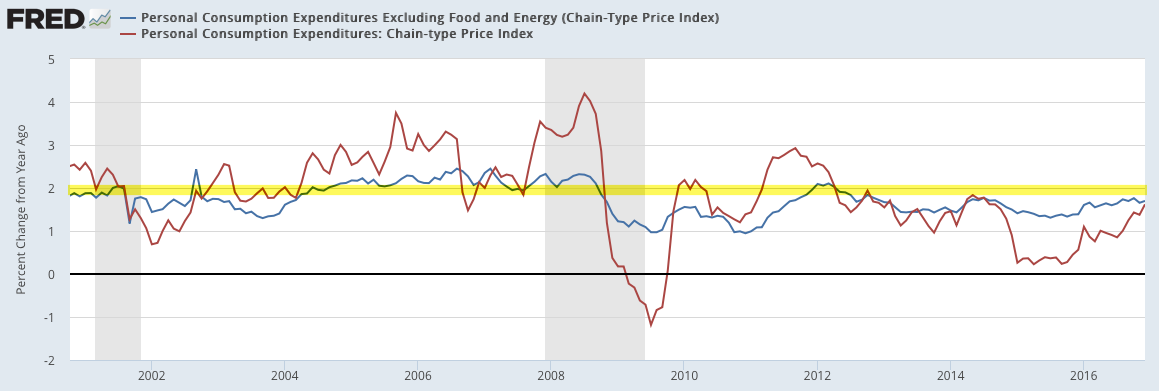

The Fed prefers to use personal consumption expenditures (PCE) to measure inflation; total and core PCE were 1.6% and 1.7% yoy, respectively, last month. Neither has been above 2% since 2Q 2012.

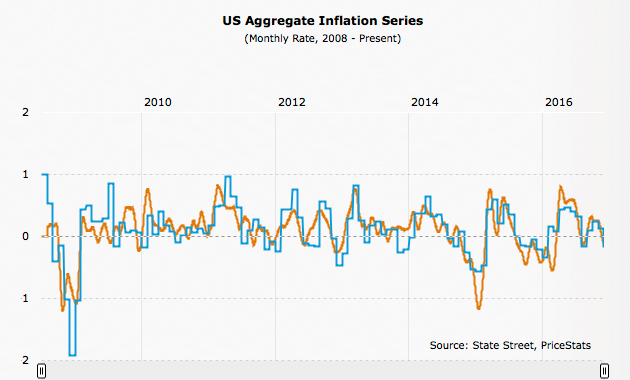

For some reason, many mistrust CPI and PCE. MIT publishes an independent price index (called the billion prices index; yellow line). It has tracked both CPI (blue line) and PCE closely.

Demand

Regardless of which data is used, real demand has been growing at about 1.5-3%, equal to about 3-4% nominal.

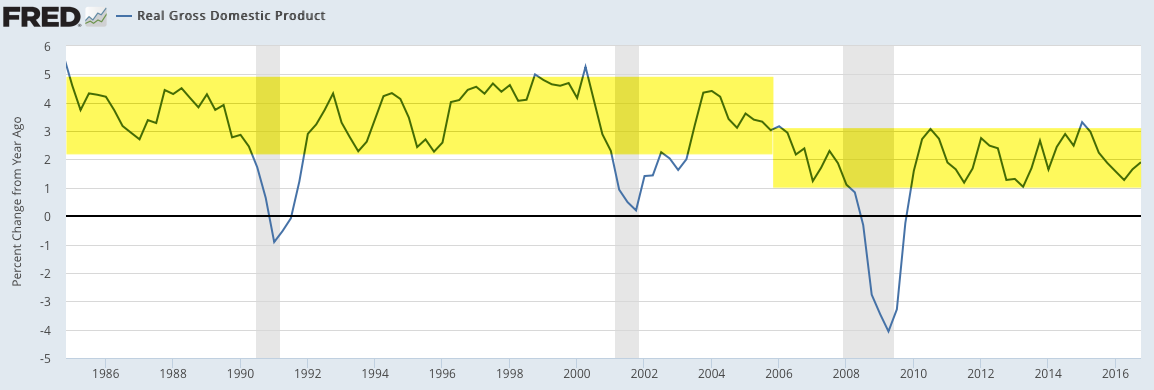

Real (inflation adjusted) GDP growth through 4Q16 was 1.9% yoy. 2.5-5% was common during prior expansionary periods prior to 2006.

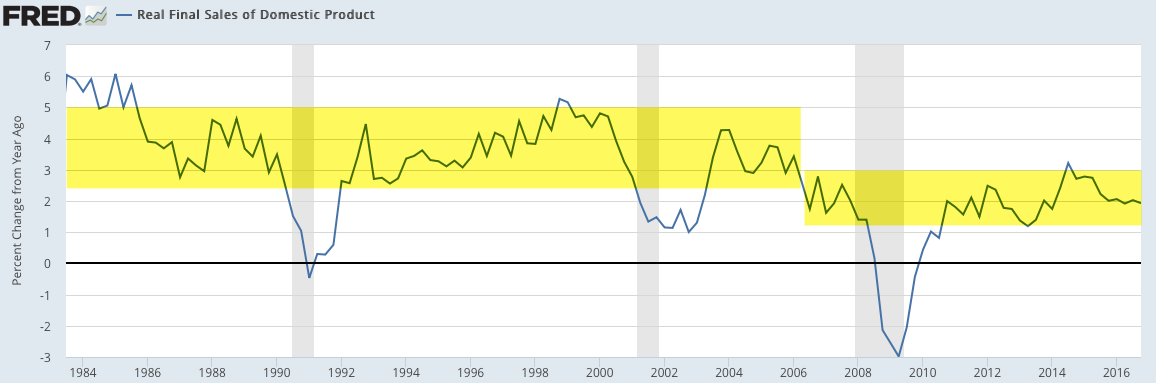

Stripping out the changes in GDP due to inventory produces "real final sales". This is a better measure of consumption growth than total GDP. In 4Q16, this grew 1.9% yoy. A sustained break above 2.5% would be noteworthy.

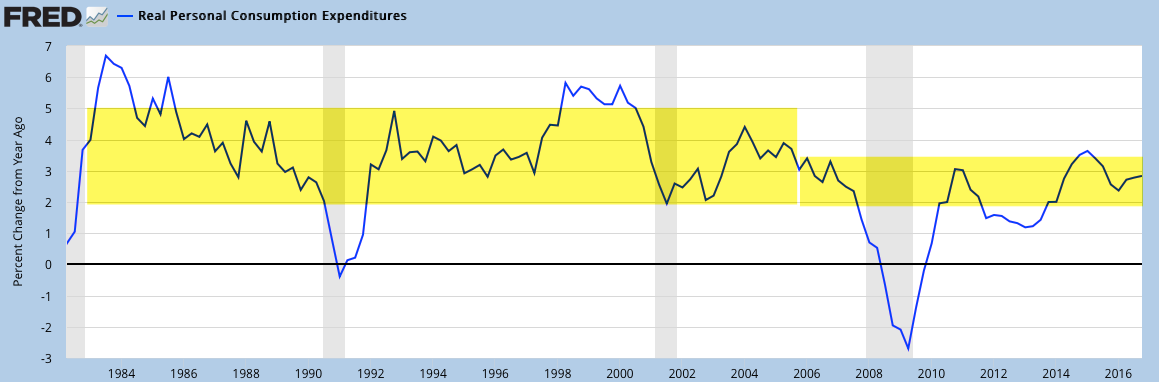

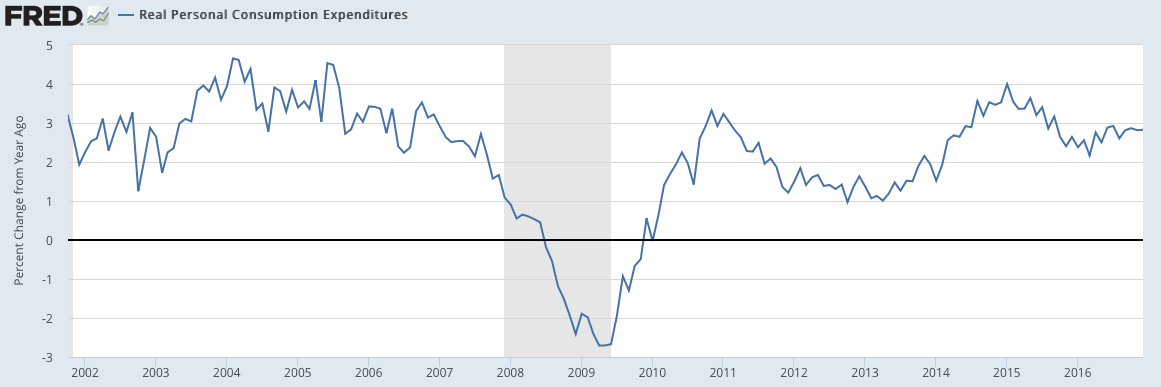

Similarly, the "real personal consumption expenditures" component of GDP (defined), which accounts for about 70% of GDP, grew at 2.8% yoy in 4Q16. The last 11 quarters have seen the highest persistent growth rate since 2006. This is approaching the 3-5% that was common in prior expansionary periods after 1980.

On a monthly basis, the growth in real personal consumption expenditures was 2.8% yoy in December. For FY2016, growth was 2.7% yoy.

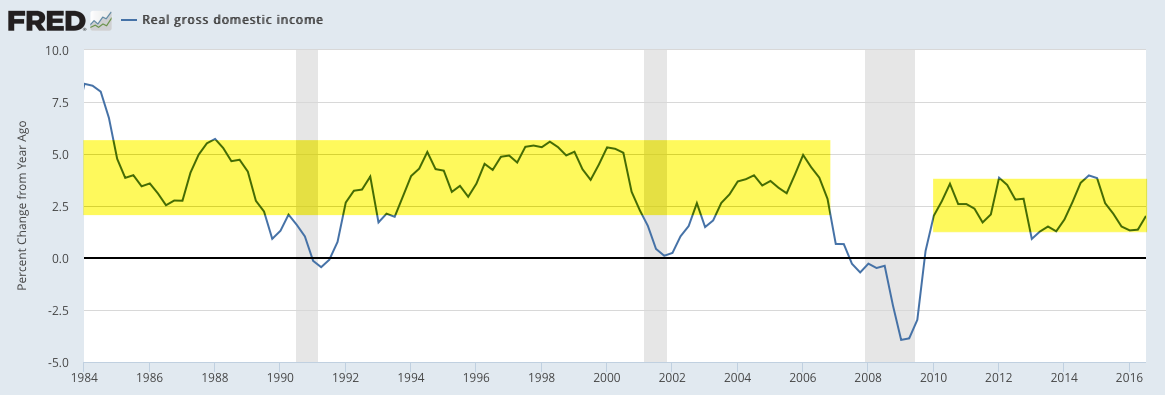

GDP measures the total expenditures in the economy. An alternative measure is GDI (gross domestic income), which measures the total income in the economy. Since every expenditure produces income, these are equivalent measurements of the economy. A growing body of research suggests that GDI might be more accurate than GDP (here).

Real GDI growth in 3Q16 was 1.9% yoy.

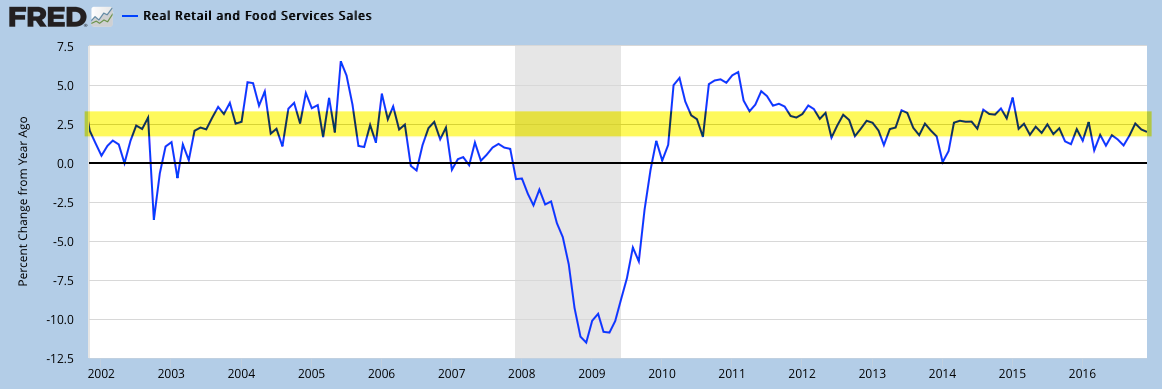

Real retail sales reached a new all-time high in December, with annual growth of 2.0% yoy. The range has generally been centered around 2.5% yoy for most of the past 20 years.

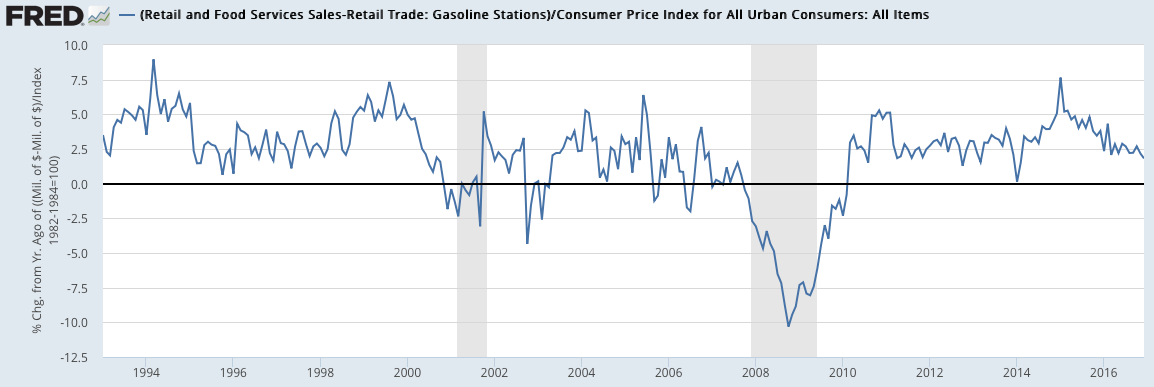

Retail sales in the past two years have been strongly affected by the large fall in the price of gasoline. In December, real retail sales at gasoline stations rose by 4% yoy after having fallen more than 20% yoy earlier in 2016. Real retail sales excluding gas stations grew 1.8% in December.

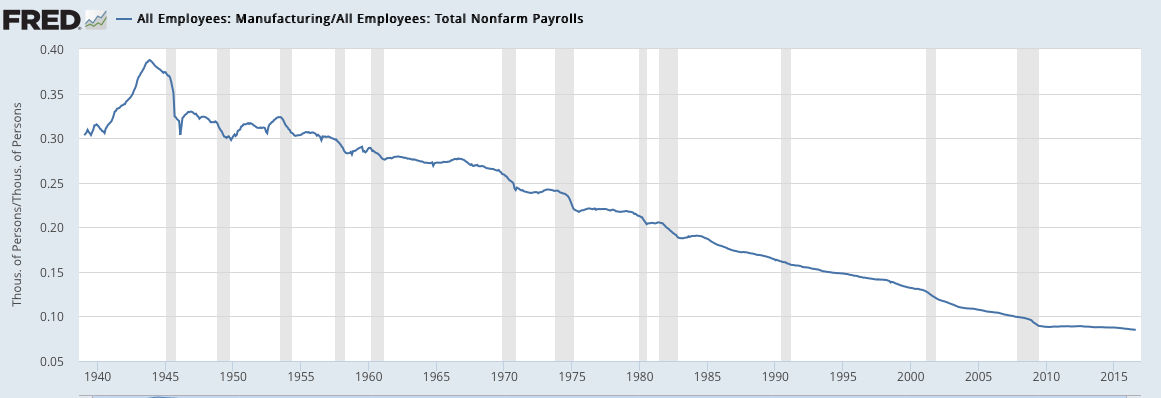

The main negatives in the macro data are concentrated in the manufacturing sector, as the next several slides show. It's important to note that manufacturing accounts for less than 10% of US employment, so these measures are of lesser importance. Even within manufacturing, the weakness is concentrated; most sectors are not contracting (more on this here).

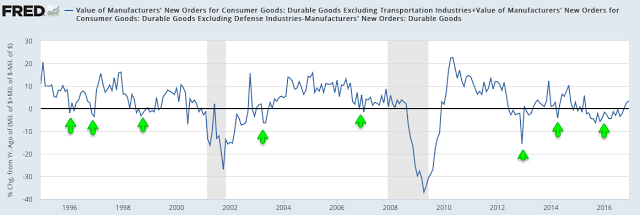

Core durable goods orders (excluding military, so that it measures consumption, and transportation, which is highly volatile) rose 3.4% yoy (nominal) in December. This is the best growth since April 2015. Weakness in durable goods has not been a useful predictor of broader economic weakness in the past (arrows).

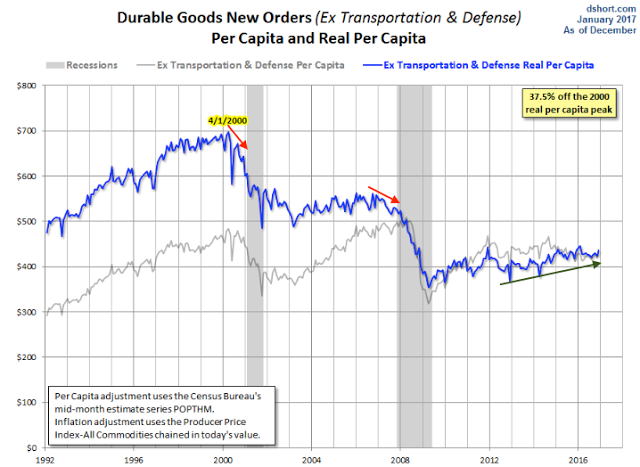

This is a nominal measure and thus negatively impacted by the weak inflation rate. On a real basis, growth continues to trend weakly higher (blue line is real; gray line is nominal; chart from Doug Short).

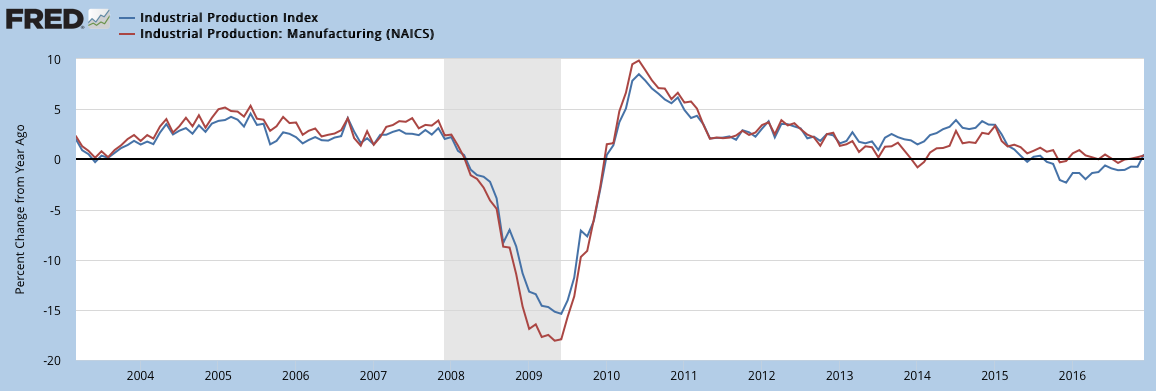

Industrial production growth grew 0.5% in December. The more important manufacturing component (excluding mining and oil/gas extraction; red line) rose 0.4% yoy. This is a volatile series: manufacturing growth was lower at points in both 2013 and 2014 before rebounding strongly.

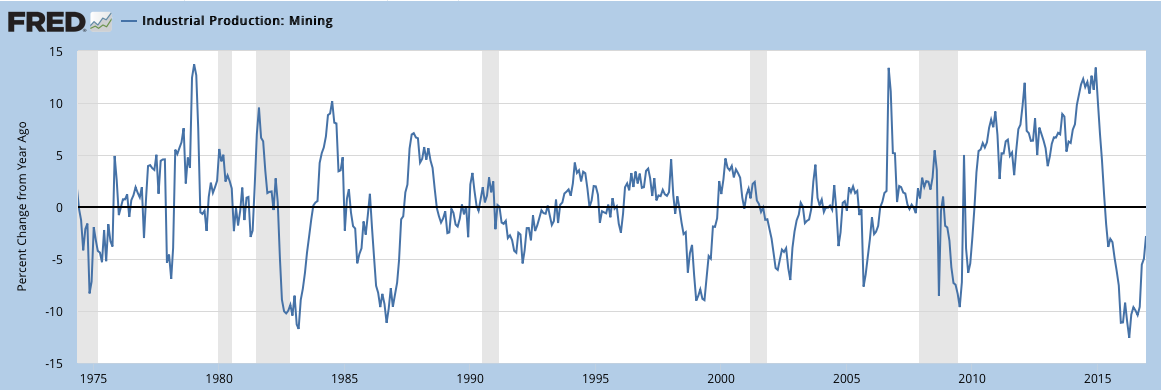

Weakness in total industrial production has been concentrated in the mining sector, which fell 4% yoy in December; the past two years have had the worst annual fall in more than 40 years. It is not unusual for this part of industrial production to plummet outside of recessions.

Housing

Housing sales grew 12% yoy in 2016. Housing starts made a 9 year high in October. Overall levels of construction and sales are small relative to prior bull markets but the trend is higher.

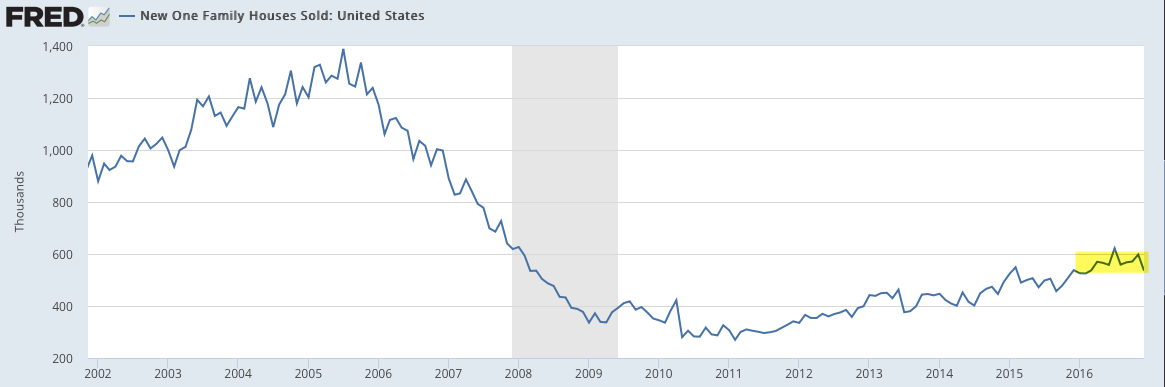

First, new houses sold was 536,000 in December. Growth was 0% over the past year after rising 9% yoy in December 2015. For all of 2016, growth in new houses sold was 12% yoy.

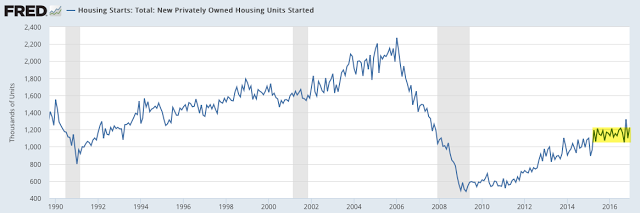

Second, overall starts made a 9 year high in October. Overall growth in starts has flattened over the previous 2 years.

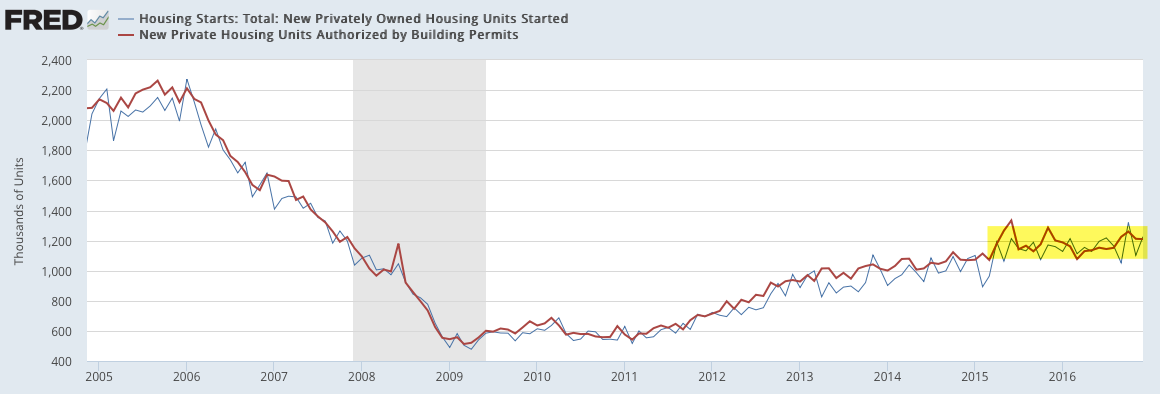

Building permits increased every month from March to October, but the overall trend in growth has been flattening since April 2015 (red line).

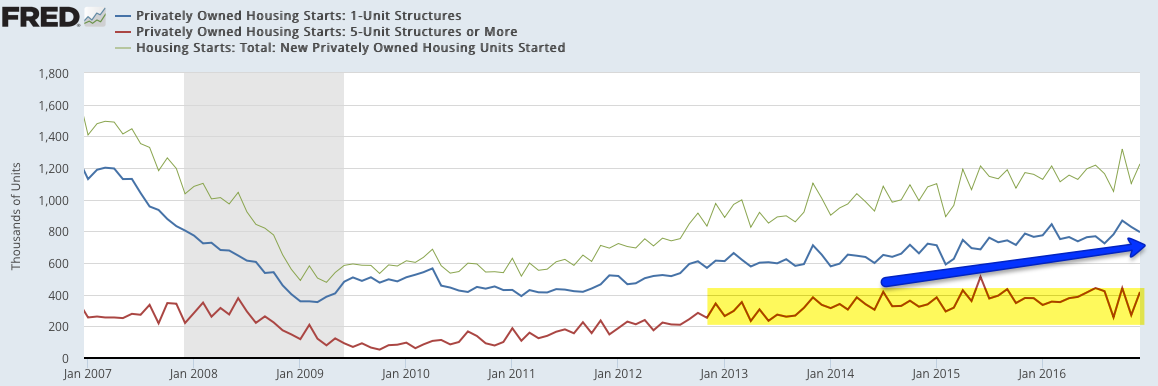

Single family housing starts (blue line) were the highest since the recession in October. Multi-unit housing starts (red line) are flat over the past four years; this has been a drag on overall starts.

Summary

In summary, the major macro data so far suggest positive, but slow, growth. This is consistent with corporate sales growth. SPX sales growth the past year has been positive but only about 2% (nominal).

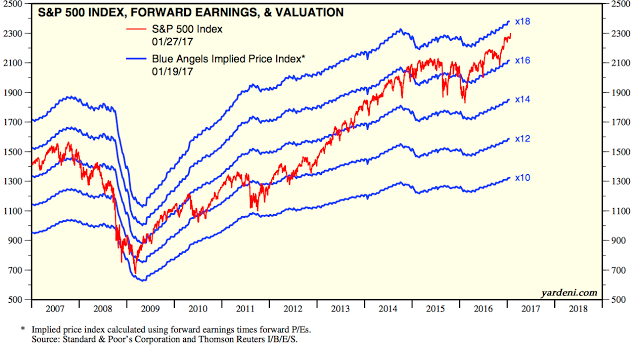

With valuations now well above average, the current pace of growth is likely to be the limiting factor for equity appreciation. This is important, as the consensus expects earnings to grow about 10% in 2017 (chart from Yardeni).

Modest growth should not be a surprise. This is the classic pattern in the years following a financial crisis like the one experienced in 2008-09. Unlike typical cyclical expansions, consumers have reduced their relative debt, and this has constrained their consumption.

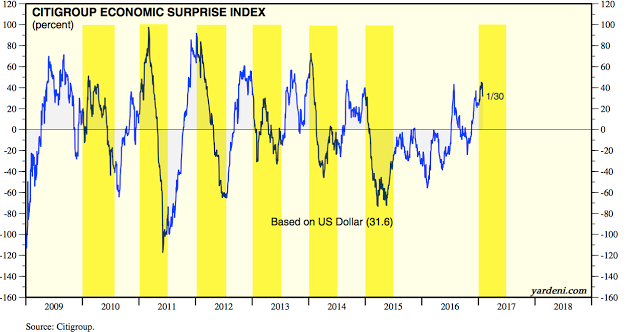

Macro data is ahead of expectations to start the year. During the current expansion, that has led to underperformance of macro data relative to expectations as the year progresses.