The economy has largely recovered from the 2020 recession. And the Federal Reserve is finally thinking about slowing down its money printing stimulus.

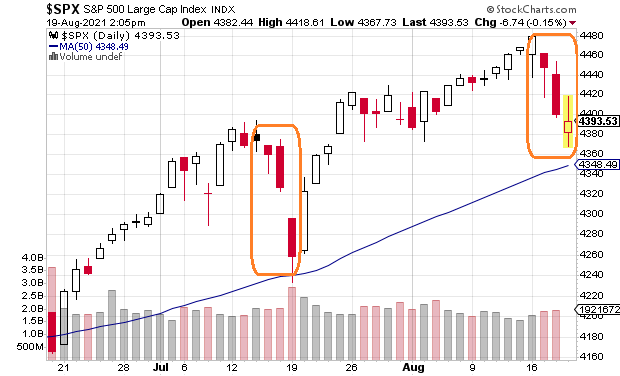

Perhaps ironically, the stock market is not too happy about it. The S&P 500 has dropped about 2% from recent highwater marks.

Is it time to insure against a significant bearish retreat? Maybe.

Then again, the current uncertainty may turn out to be no different than the correction and the subsequent buy-the-dip behavior that occurred in July. Additionally, the 50-day moving average tends to behave as a strong area for price support.

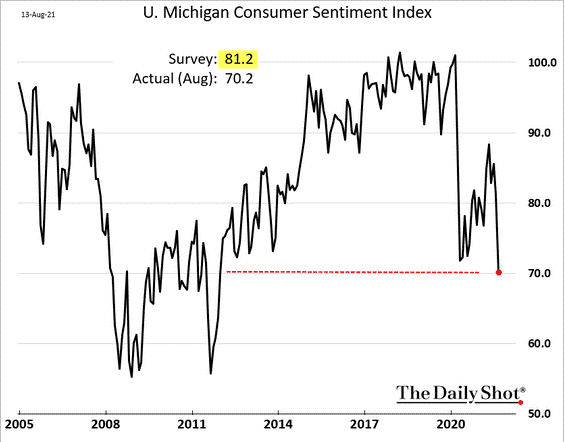

On the flip side, the stock bubble could continue to deflate if consumer sentiment fails to improve. The most recent reading was the lowest in a decade.

Why are consumers so gloomy? Shouldn’t they be excited by the free money that they received from the federal government as well as by record-breaking highs in 401k accounts?

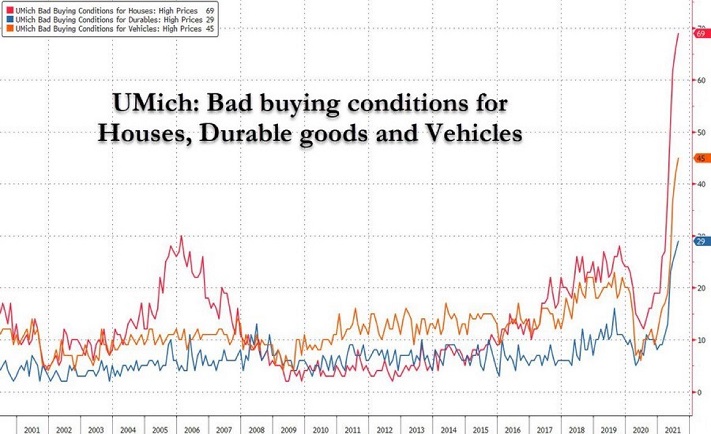

Unfortunately, many are fretting inflation (a.k.a. higher prices) in everything from refrigerators to air conditioning units, cars to trucks, home furnishings to residences themselves. Indeed, pessimism is literally leaping off the chart.

This leaves the Federal Reserve in a quandary. Reining in money printing stimulus, either by slowing the pace of bond purchasing activity or by raising the overnight lending rate, could curtail inflationary pressure. Doing so, though, sends a psychological signal to investors that the Fed may be less inclined to pump stocks up through direct or indirect support.

In a nut shell, the Fed has made the near-term wonderful for stocks, at the expense of longer-term outcomes. The minute the Fed shifts its attention to longer-term concerns, like “inflation gone wild” and/or “asset bubbles,” the shorter-term for stocks can get ugly. Perhaps very ugly.

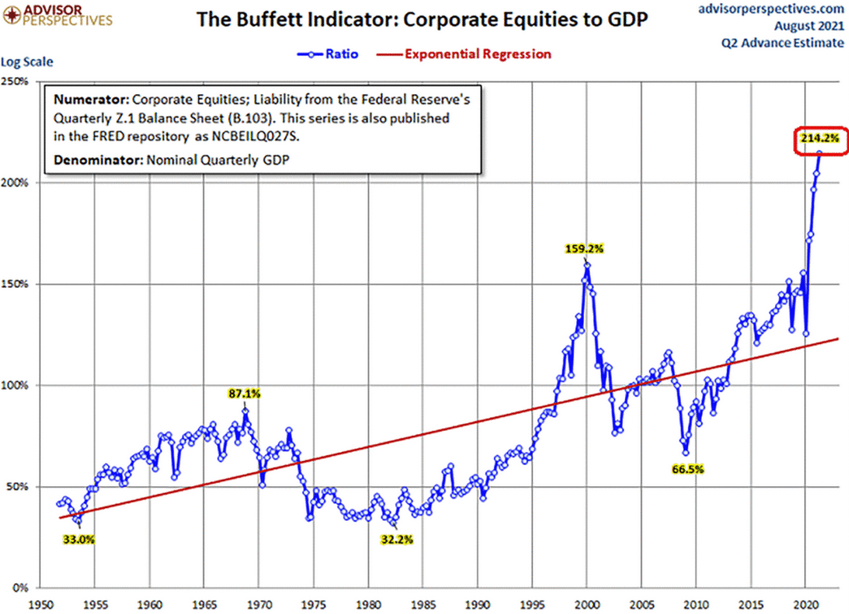

Consider the stock valuation metric that compares market capitalization (i.e., the total value of all stock shares) to the economy (GDP). The measure is also known as the Warren Buffett indicator. Corporate equities have never been so out of line with the underlying economy than they are right now.

The implication? Stocks could get whacked in ways that made the tech bubble of 2000 look tame.

Obviously, the Federal Reserve would do everything in its power to prevent prices from reverting to mean/median pricing. Yet the central bank may be willing to let milder bear markets develop — 20%-25% drawdowns — if committee members see a definitive need to fight longer-lasting inflation.

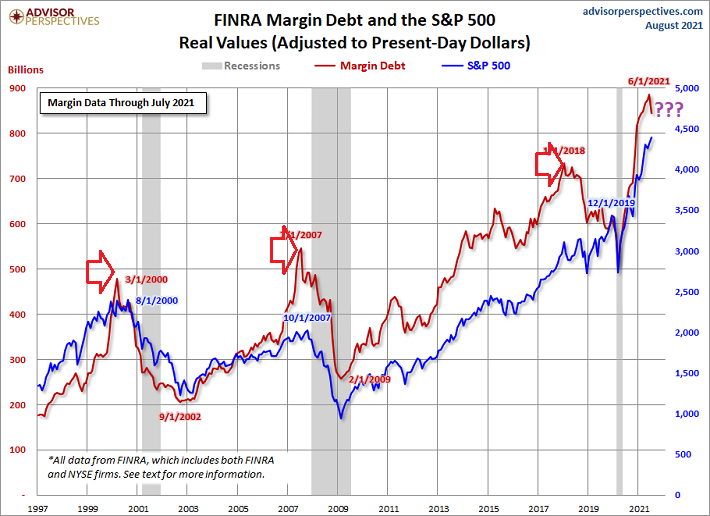

In truth, some folks may already be unwinding their “bets.” The use of margin debt to juice stock gains declined meaningfully since peaking in June. (Note: Margin debt tops have preceded significant 21st century sell-offs.)

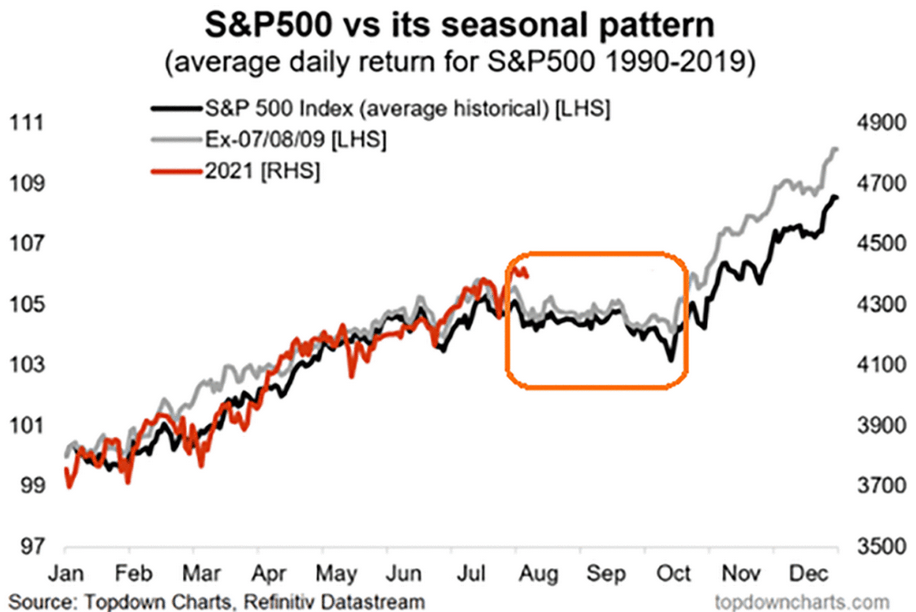

Even the seasonal trends may be unfavorable for stocks at S&P 4400-4475.

It is fair to question what can happen if the Fed slows down its money creation sooner rather than later. It would mean the Fed would be creating less money to buy bonds from others in the economy. And the person/government/institution that does not receive cash from selling its bonds to the Fed will not have that additional cash to put to work in stocks.

In other words, stock bubble participants have benefited tremendously from a whole lot of buyers of stock pressuring very few sellers. (The dynamics in residential real estate has been eerily similar.) This is what happens when the Fed entices bondholders to accept cash and invest the proceeds elsewhere.

With the Fed backing off, however, there may be significantly fewer buyers of stock shares. And if participants fear the top is in, there could be a mad rush for a narrow exit door.