My grandfather was never rich. He did have some money in the 1920s, but he lost most of it at the tail end of the decade. Some of it disappeared in the stock market crash in October of 1929. The rest of his deposits fell victim to the collapse of New York’s Bank of the United States in December of 1931.

I wish I could say that my grandfather recovered from the wrath of the stock market disaster and subsequent bank failures. For the most part, however, living above the poverty line was about the best that he could do financially, as he buckled down to raise two children in Queens.

There was one financial feature of my grandfather’s life that provided him with greater self-worth. Specifically, he refused to take on significant debt because he remained skeptical of credit. And with good reason. The siren’s song of “you-can-pay-me-Tuesday-for-a-hamburger-today” only created an illusion of wealth in the Roaring Twenties; in fact, unchecked access to favorable borrowing terms as well as speculative excess in the use of debt contributed mightily to the country’s eventual descent into the Great Depression. G-Pops wanted no part of the next debt-fueled crisis.

Here’s something few people know about the past: Consumer debt more than doubled during the ten year-period of the Roaring 1920s (1/1/1920-12/31/1929). And while you may often hear the debt apologist explain how the only thing that matters about debt is the ability to service it, the reckless dismissal ignores the reality of virtually all financial catastrophes.

During the Asian Currency Crisis and the bailout of Long-Term Capital Management (1997-1998), fast-growing emerging economies (e.g., South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, etc.) experienced extraordinary capital inflows. Most of the inflows? Speculative borrowed dollars. When those economies showed signs of strain, “hot money” quickly shifted to outflows, depreciating local currencies and leaving over-leveraged hedge funds on the wrong side of currency trades. The Fed-orchestrated bailout of Long-Term Capital coupled with rate cutting activity prevented the 19% S&P 500 declines and 35% NASDAQ depreciation from charting a full-fledged stock bear.

Did we see similar debt-fueled excess leading into the 2000-2002 S&P 500 bear (50%-plus)? Absolutely. How long could margin debt extremes prosper in the so-called New-Economy? How many dot-com day-traders would find themselves destitute toward the end of the tech bubble?

Bring it forward to 2007-2009 when housing prices began to plummet in earnest. How many “no-doc” loans and “negative am” mortgages came with a promise of real estate riches? Instead, subprime credit abuse brought down the households that lied to get their loans, destroyed the financial institutions that had these “toxic assets” on their books, and overwhelmed the government’s ability to manage the inevitable reversal of fortune in stocks and the overall economy. Just like 1929-1932. Just like 1997-1998. Just like 2000-2002.

Maybe investors have already forgotten the sovereign debt crisis from the summer of 2011. They were called the “PIGS” – Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain had borrowed insane amounts to prop up their respective economies. The easy access to debt combined with the remarkably favorable terms – a benefit of being a member of the euro zone – started to come undone. Investors rightly doubted the ability of the PIGS to repay their respective government obligations. Yields soared. Global stocks plunged. And central banks around the world had to come to rescue to head off the disastrous declines in global stock assets.

Throughout history, when financing is cheap and when debt is ubiquitous, someone or something will over-indulge. Today? Households may be stretched in their use of cheap credit, and they have not truly deleveraged form the Great Recession. Yet the average Joe and Josephine have not acted as recklessly as governments around the globe. In the last few weeks alone, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced an increase in its bond-buying activity as well as the type of bonds it is going to acquire, Japan has sold nearly $20 billion in negatively-yielding bonds and the U.S. has downgraded its rate hike path from four in 2016 to two in 2016. Add it up? The world is going to keep right on going with its debt binge.

Are we really that bad her in the U.S.? Over the last seven years, the national debt has jumped from $10.6 trillion to $19 trillion. In 7 years! If interest rates ever meaningfully moved higher, there would be no chance of servicing our country obligations. We would likely be facing the kind of doubt that occurred with the PIGS in 2011, as we looked for bailouts, write-downs, dollar printing and/or methods to push borrowing costs even lower than they are today.

That’s not the end of it either. The biggest abusers of leverage and credit since the end of the Great Recession? Corporations. There are several indications that companies are already seeing less bang for the borrowed buck. For instance, low financial leverage companies in iShares MSCI Quality Factor (QUAL) have noticeably outperformed high financial leverage companies in the PowerShares Dynamic Buyback Achievers Portfolio (NYSE:PKW) since the May 21, 2015 bull market peak.

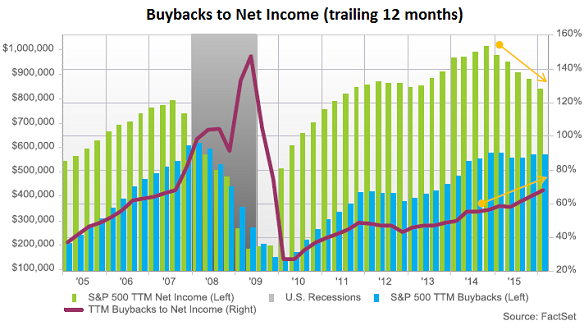

It gets more ominous. The enormous influence of stock buybacks by corporations – where companies borrow on the ultra-cheap and acquire shares of their own stock to boost profitability perceptions as well as decrease share availability – may be fading. For one thing, buyback activity has not stopped profits-per-share declines across S&P 500 companies for 4 consecutive quarters (Q2 2015, Q3 2015, Q4 2015, Q1 2016 est).

Equally worthy of note, when the bottom line net income of S&P 500 corporations began to decline in earnest in 2007, buybacks began to decline in earnest in 2008. Bottom-line net income has been deteriorating since 2014, but favorable corporate credit borrowing terms has kept buybacks at a stable level into 2016. Nevertheless, once corporations begin recognizing that the buyback game no longer produces enhanced returns (per the chart above) – that stock prices falter in spite of the buyback manipulation efforts, they could begin to reduce their buyback activity. When that happened in 2008, the lack of support went hand in hand with a 50%-plus decimation of the S&P 500.

The ratio of buybacks to net income in the above chart can become problematic when companies spend a whole lot more of their bottom-line net income on share acquisition. Maybe it’s a positive thing as long as stock prices are going higher. Yet FactSet already reports that 130 of the 500 S&P corporations had a buyback-to-net-income ratio higher than 100%. Spending more than you earn on acquiring shares of stock? That means zero dollars are going toward productive use, including human resources, research/development, roll-out of new products and services, equipment, plants and so forth.

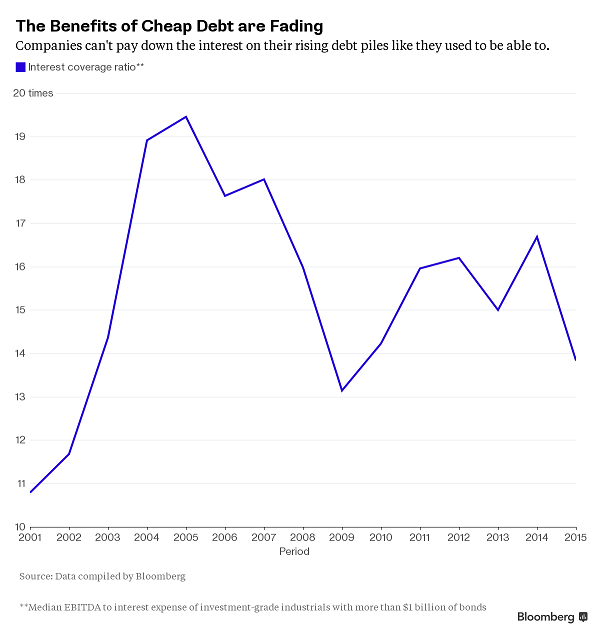

Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if one could forever count on the notion that interest expense would be negligible. Unfortunately, when total debt continues to rise, even rates that stay the same become problematic. Consider the evidence via “interest coverage.” In essence, the higher the interest coverage ratio, the more capable a corporation is at paying down the interest on its debt. Yet if the debt is rising and the interest rates are roughly the same, interest expense increases and the interest coverage ratio decreases. Here’s a chart that shows challenges in the investment grade, top-credit rated universe. You decide.

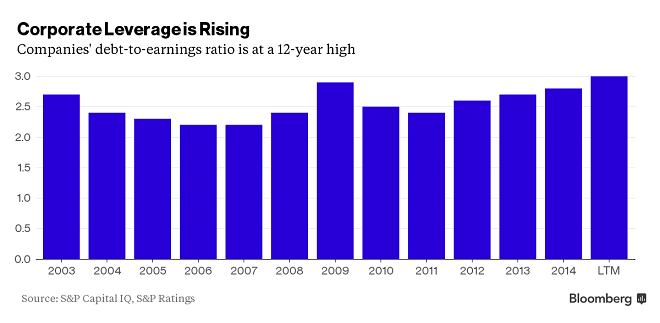

There are still other signs that show a potential “tapping out” for corporations. Corporate leverage around the globe via the debt-to-earnings ratio has hit a 12-year high. Aggressive financing in the expansion of debt alongside additional interest expense is rarely a net positive. On the contrary. Aggressive leveraging typically means a high level of risk. Granted, if corporations were taking on more debt to increase their value via new projects, expansion, new products, growth and so forth, it might represent high risk-high reward. In reality, however, everyone recognizes that the game has been about loading up on debt at the ultra-low costs to acquire stock shares – a short-sighted practice of enhancing earnings-per-share numbers for shareholders.

In sum, low rates alone won’t make it easier for corporations to pay off their substantial obligations. Paying down debt is more challenging in low growth environments – 1.0% GDP in Q4 2015 and 1.4% GDP estimate for Q1 2016. Why might that be so? Corporations did not choose to put borrowed money into capital investments that might ultimately help service interest expense. Stock buybacks? Additional stock shares cannot provide the cash flow necessary for debt servicing the way that capital investments can.

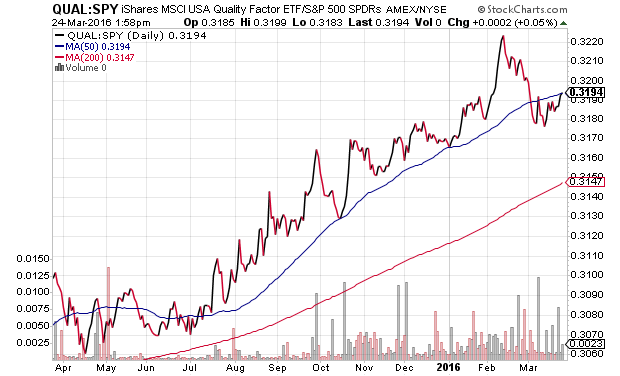

To the extent one has equity exposure, he/she would be wise to limit highly indebted, highly leveraged companies. The steadily rising price ratio between QUAL and the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSE:SPY) Trust (AX:SPY) tells me that investors are wising up. In particular, they’re more concerned by poor credit risks across the stock spectrum. And while QUAL certainly won’t provide bear market protection on its own, it will likely lose less in downturns; it will likely hold its own during up swings.

Disclosure: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc, and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert web site. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationships.