If Mario Draghi was lacking ammunition to initiate an outright quantitative easing program in the Eurozone, he certainly has it now. Even the staunchest opponents will have a tough time arguing against the need for a more aggressive approach to monetary easing. Here are five reasons:

1. The take-up on ECB's TLTRO offering (see post) fell far short of the ECB’s goals. Indeed the demand in the second round of the offering came in at €130 bn, putting the total take-up at €212bn - well below the €400 billion allowance. Since the TLTRO financing is linked to bank lending, the program to some extent relies on demand for credit from businesses and consumers. And that demand has been lackluster in the past couple of years. Therefore the initiatives announced by the ECB last summer, including ABS and covered bond purchases, are simply insufficient for the type of monetary expansion (of about €1 trillion) the central bank would like to see in the Eurozone.

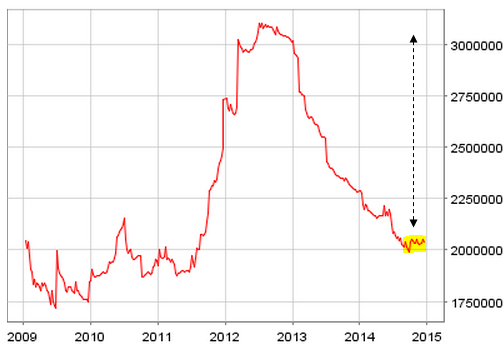

|

| Eurosystem consolidated balance sheet (source: ECB) |

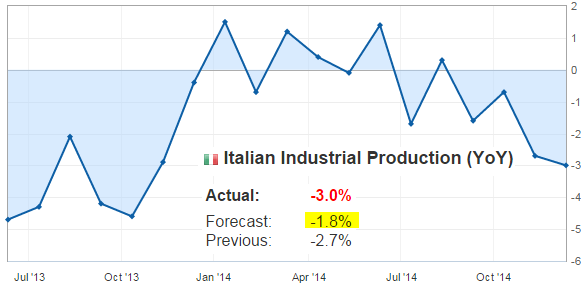

2. Some Economic data out of the Eurozone shows recovery stalling. Italian industrial production and French labor markets are just two examples.

|

| Source: Investing.com |

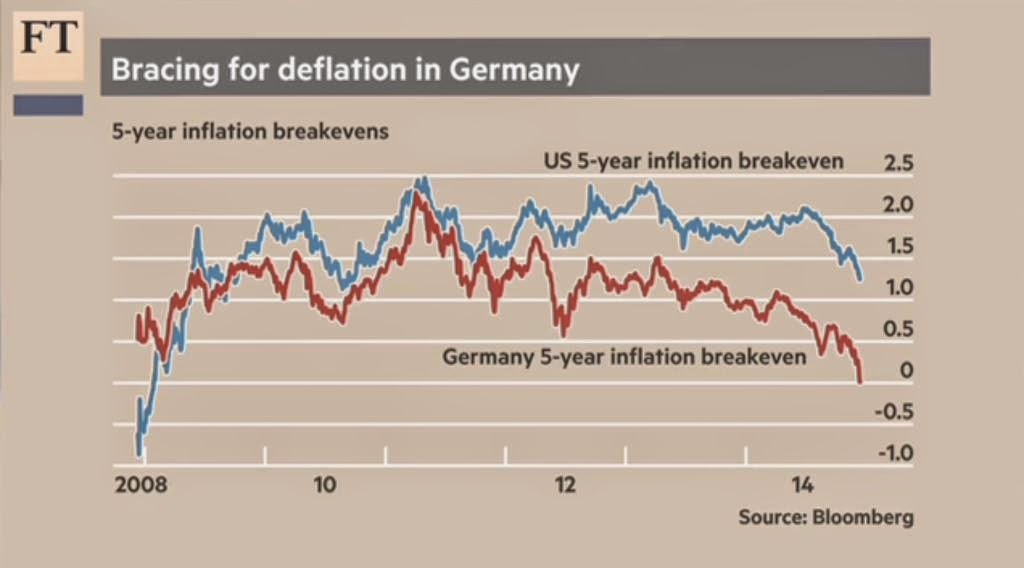

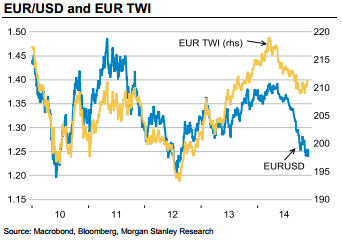

4. While the euro has declined significantly against the dollar, it remains quite strong on a trade-weighted basis. This is putting downward pressure on prices (via cheaper imports) and is disadvantaging some of the Eurozone-based exporters. A more aggressive easing effort would force the euro lower.3. With the collapse of oil prices, the Eurozone is bracing for deflation. Germany 5-Year breakeven inflation expectations are now at zero. And Europe's central bankers are fearful of repeating Japan's decade-long struggle with deflation.

|

| TWI = "trade-weighted index" (source: @TenYearNote) |

5. Finally, the euro area's sovereign risks are resurfacing once again - triggered by new political uncertainty in Greece.

The Guardian: - Mounting concerns over Greece’s ability to weather a presidential election, brought forward in a surprise move by the prime minister, Antonis Samaras, continued to unnerve investors ahead of the first round of the vote in the Greek parliament next week.

Under Greek law failure to elect a new head of state by the ballot’s third round on 29 December could trigger a general election. The stridently anti-bailout main opposition party, Syriza, is tipped to win that poll. The radical leftists have made a debt writedown and the end of austerity their overriding priorities if voted into office.

Although Samaras called the election in a bid to expunge the political uncertainty engulfing Greece, the slim majority held by his government, compounded by the leader’s repeated warnings of Greece leaving the eurozone if Syriza assumes power, has accelerated investor nervousness.

The nation's stock market is down 20% over the past 5 days as investors flee.

|

| red = Euro STOXX 50, blue = Athens Composite |

And Greek sovereign debt sold off sharply. In fact the 3-year government paper yield went from roughly 3.5% in September to 11% now.

Mario Draghi now has five solid reasons to argue for QE and many expect the central bank to announce such an initiative in the next 2-3 months. However, while most economists covering the euro area agree on the need to take a more aggressive monetary action, the problem of implementation remains. Since the Eurosystem's (ECB's) balance sheet is in effect owned by member states, many in the core economies are worried about having to become the proud owners of large quantities of their pro rata share of periphery nations' debt. For the Germans in particular, the ownership of such debt is a major issue. A solution that is even remotely politically palatable across the Eurozone remains elusive. The ECB's independence and the euro area's legal structure is about to be tested once again.