The case for the continuation of the U.S. bull market heavily rests on the shoulders of steady economic growth and low interest rates (on an absolute basis). Many believe that, as long as these circumstances exist, stocks will provide venerable results.

However, market participants might want to consider a similar period in history – a time span when the 10-year treasury offered paltry yields, gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a reasonable clip and the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy. In late 1936, GDP had been growing steadily and the 10-year yield averaged 2.6%. The Fed chose to modestly compress the money supply after years of extraordinary stimulus. Indeed, the 1929-1932 “Great Depression” seemed as though it had been been vanquished.

Unfortunately, by the second quarter of 1937, investors became alerted to signs of economic deceleration. Risky assets began to falter. The Fed quickly reversed course from tightening to easing, even engaging in market-based asset purchases. To no avail. An insipid recession occurred in spite of the central bank’s rapid policy reversal. Before all was said or done – by the time the 1937-1938 bear had finally ended – stocks had already plummeted 51.5%.

Here in 2015, we have experienced steady economic growth for six-plus years with GDP expanding at approximately 2.2% per year. It has been an anemic recovery, but an expansion nonetheless. (Indications of economic deceleration abound.) Meanwhile, the U.S. stock bull has been remarkably robust, both in duration and magnitude. One researcher estimates that the current bull market period has been more powerful (since 3/09) than 90% of the preceding rallies since 1900. (See chart below.)

Similar to the circumstances in late 1936, when the economy appeared relatively healthy, stocks performed admirably, and the Fed started to tighten monetary policy after a long hiatus, the 2015 Fed recently embarked on its first overnight lending rate hike. Those who ignore the similarities say that it is only 25 basis points; they believe that members of today’s Federal Reserve are smarter than their predecessors and that they would not endeavor to normalize borrowing costs unless the economy were strong enough to withstand the shift. Me? I am skeptical.

Here are three additional similarities between 1937 and right this moment:

1. The Last Time Stocks, Bonds, And Cash Did Not Work. Asset allocation is not working. Granted, the iShares S&P 500 (N:IVV) is up 3% through December 2009, with 1% coming on today’s (12/29) price jump and the rest of it coming from dividends. Yet the iShares Mid-Cap ETF (N:IJH) that tracks mid-sized corporations in the S&P 400 logged -0.5% through 12/29 and the iShares Russell 2000 (N:IWM) that tracks small-cap stocks registered -2.3% through 12/29.

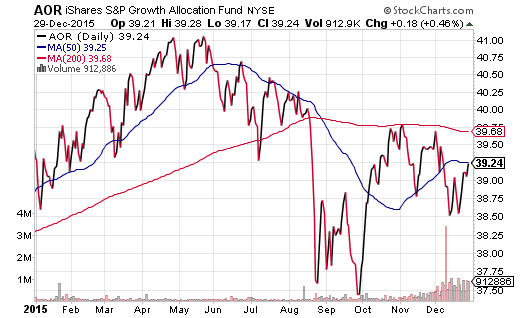

The more that one diversifies, the worse things get. Add foreign stocks via iShares All-World excluding U.S (O:ACWX) for -4.0%. Inject iShares High Yield Corporate Bond (N:HYG) for -5.2%. Dare to emerge with Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets (N:VWO) for -14.7%. In fact, Bloomberg tracked 35 ETFs that invest in different asset types to uncover a median loss (-5.0%). Even the all-in-one solution via iShares Core Growth Allocation (N:AOR), which offers 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds, served up a negative result (-0.7%).

According to research compiled by Bianco Research LLC in conjunction with Bloomberg, you have to go back to 1937 to find a 12-month run where asset allocation performed as poorly. Coincidence? Could be. Or perhaps investors in 1937 struggled with the same concerns about a return OF capital as opposed to a return ON capital.

2. Overvaluation Then, Overvaluation Now. Nobel laureate in economics, James Tobin, proposed that the combined market value of all companies listed on the exchanges should be roughly equal to their replacement costs. He then developed the “Q Ratio,” which divides the total price of U.S. stocks by those replacement costs of corporate assets. Tobin’s Q hit 1.1 earlier this year, suggesting that stocks traded 10% above the value of companies’ assets.

Not so bad? That reading has only been surpassed by the year 2000. Moreover, if one assumes the year 2000 was a moment of ridiculous dot-com euphoria, you’d have to go back to 1937 to find a reading that suggests similar overvaluation.

Keep in mind, this ratio has only surpassed the 1.0 threshold on one-tenth of trading sessions, most of which occurred in the late 1990s. The average (mean) Q ratio is approximately 0.68.

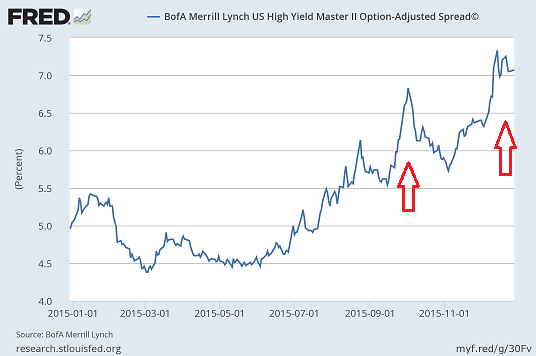

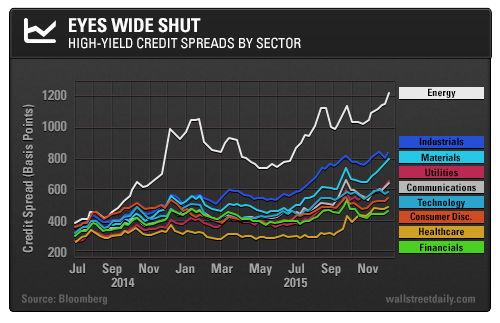

3. “Spread Spike” For High-Yield Bonds. Back in May of 1937, the high-yield bond spread rocketed 85 basis points. Here in 2015? We have two occasions where high yield bond spreads have spiked by more than 1%.

Normal market fluctuations? Hardly. When investors abandon the credit markets, they are concerned about a wave of corporate defaults. And they’re not just worried about energy defaults either. High-yield corporate credit is struggling clear across all sectors of the economy. (See Bloomberg chart below.)

Are the circumstances in 2015 identical to those in 1937? Of course not. Every well-read market participant recognizes that history has a habit of rhyming, not repeating. Nevertheless, keeping a higher allocation to cash than you might otherwise keep is sensible in this late-stage stock bull.