There was a time when hedge funds may have offered something unique in the way of performance. You may have been able to make a case for them alongside a mix of stocks and intermediate-term treasury bonds. Over the last three years, however, hedge funds have been downright abysmal.

Consider the IQ Hedge Multi-Strategy Index ETF (NYSE:QAI). It endeavors to replicate hedge fund performance across a variety of investment styles, including long/short equity, market neutral, fixed-income arbitrage, volatility and event-driven financial gain (e.g., “Brexit,” yuan devaluation, etc.).

Yet QAI has provided very little value relative to the SPDR S&P 500 (NYSE:SPY) and/or iShares 7-10 Year Treasury Bond (NYSE:IEF).

The collective woes of hedge funds notwithstanding, it’s difficult to dismiss some of the titanic personalities in the industry. Stanley Druckenmiller admonished SOHN Investment Conference attendees to “get out of the stock market” back in May. And according to the Wall Street Journal, George Soros began making a series of monstrously bearish bets against equities in May and June. Both men have revealed significant stakes in gold.

Perhaps hedge funds as a group have lost their allure. Still, it is difficult to dismiss Druckenmiller or Soros outright. And they’re hardly the only big time names to warn the investment community. Bill Gross, the former king of bond mutual funds at PIMCO, recently told his followers that he does not like bonds, stocks or private equity. (Note: He likes gold). Jeff Gundlach, the reigning monarch in bond mutual fund investing, growled last Friday, “Sell everything!”

Are all of these famous financial minds out of touch? I doubt it. Each of them believes that central banks around the globe have forced rates lower for far too long; each of them believes that central banks have fostered a credit balloon that has become unmanageable.

Ironically enough, a lesser-known figure in finance, Jerry Haworth of 36 South Capital Advisors, served up the most quotable description of the dilemma. He recently said, “Even a homeless person can service a $1,000,000,000 loan at zero percent.”

Inelegant? Lacking tact? Out of the mouth of the CEO of a hedge fund… sure.

On the other hand, the man has made a valid point. Developed world governments and scores of corporations no longer have an ability to pay back what they have borrowed. Zero percent rate policy (ZIRP) may permit some of them to service their debts for a while, though this does not alter the reality that current borrowing costs must be constrained where they are. (Think QE, ZIRP and NIRP forever).

If borrowing costs move meaningfully higher, default and debt restructuring result. If they do not move meaningfully higher, governments and high-risk corporations will keep borrowing until creditors wake up to the reality that there are no genuine prospects of principal repayment.

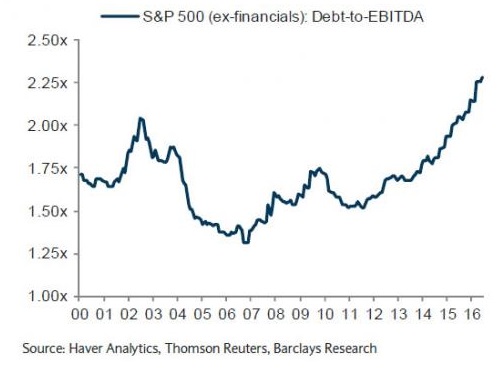

Debt may even be a problem for the best run corporations within the S&P 500 itself. The debt-to-EBITDA ratio for the S&P 500 (ex-financials) – a leverage gauge addressing the number of years it would take for a company to pay back its obligations – has surged to its highest peak in the 21st century.

We can also apply the issue of debt as well as debt servicing to the global economy itself. Central banks around the world implement unconventional quantitative easing/QE/electronic money creation to stimulate economic progress. If the economy improves, stimulus withdrawal results in economic slowdown and financial market mayhem.

If the economy does not respond to initial measures, central bankers feel compelled to provide more “cow bell” so that unqualified borrowers can service interest obligations that will never be paid back. Trapped near zero… any way the world turns.

Bull market devotees will tell you that a stock market climbs a wall of worry. I might buy that cliche with respect to Great Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. You can even sell that to me on three consecutive quarters of economic anemia at 1%.

On the flip side, corporate earnings have declined for five consecutive quarters. Corporate sales have fallen for six. Full-year corporate earnings will be negative for the second consecutive year. And at the present moment, collective corporate earnings at $87.12 are less than what companies served up four years ago (June 2012).

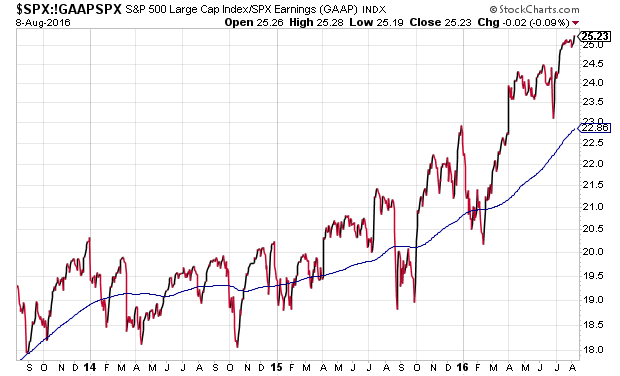

It follows that prices relative to profits (earnings) represent some of the highest valuation levels (P/E) ever. More troubling? The pace at which the P/E is rising as depicted by its 200-day trendline in the chart below.

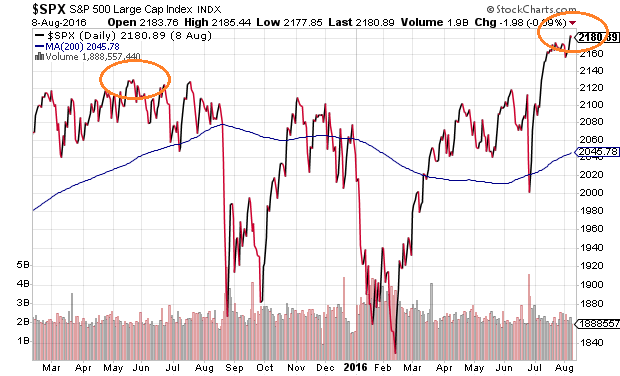

Remember, valuations are skyrocketing. Price gains for the S&P 500? Not so much. In spite of media hoopla, the S&P 500 has only tacked on about 2.4% in 15 months. (And that came with two 10%-plus violent corrections).

Historically speaking, P/Es typically expand when earnings are growing, even if they are growing at a slower pace than stock prices themselves. What’s more, when profits have declined for two consecutive quarters in the past, stock bear markets of 20%-plus materialized in all but one occasion in the 1980s.

Here we are looking at five consecutive quarters that will inevitably become six in Q3. Yet one is supposed to believe that the promise of earnings growth returning in Q4 of 2016 is the reason to maintain a high degree of confidence in stock price appreciation? Please.

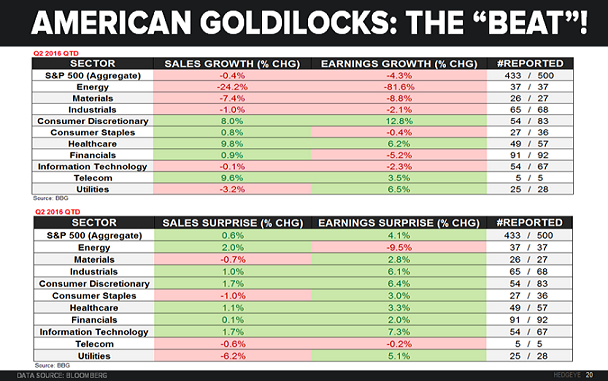

Some believe that one can simply exclude “energy” from the profit picture. Even that silliness does not hold up to scrutiny. There are more S&P 500 segments with declining year-over-year earnings than those where earnings per share are growing.

Here’s the bottom line. Bad news from the “Brexit vote” to oil prices falling from $50 back down to $40 to anemic GDP are driving longer-term interest rates lower. The bad news is also keeping the Federal Reserve on the sideline – an institution that would rather talk about economic progress than raise borrowing costs to back up their statements. Consequently, many participants believe they do not have an alternative to stocks.

From my vantage point, however, a tactical shift toward a more conservative stance has been warranted for 20 some-odd months. Whereas my clients may have had 65%-70% in a wide-range of equity (e.g., large, small, growth, value, foreign, etc.), I have maintained a lower-risk profile of 45%-50% high quality stock.

ETFs like iShares MSCI Quality Factor (NYSE:QUAL), PowerShares S&P 500 Quality Portfolio (NYSE:SPHQ) and Vanguard Dividend Growth (NYSE:VIG) fit the bill.

Similarly, clients used to have 30%-35% in a wide range of income producers (e.g., long, short, investment grade, higher-yielding, convertible, foreign, etc.). Today, 25%-30% in investment grade bonds such as iShares 7-10 Year Treasury (IEF), SPDR Nuveen Muni Bond (NYSE:TFI) and Vanguard Long-Term Corporate (NASDAQ:VCLT) have met our criteria.

The 20%-30% cash component? I regard it as our most important asset class. Not only has it been an important buffer against significant bouts of volatility over the last 15 months, but it remains ready to deploy for future opportunities.

While no person can know the precise moment that market-based securities will get beaten with the incredibly ugly stick, I know that we will be well-positioned to acquire low-priced assets when they become available once again.