If only James Bullard had had his way. The head of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis was the only voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) who wanted to cut the Fed’s benchmark rate by a half-point, instead of the quarter-point decided on by seven other voters.

In fact, the decisions of the policymaking panel, usually driven by consensus, are coming to resemble split decisions at the Supreme Court. Two other voting members, Kansas City Fed Chief Esther George and Boston Fed Chief Eric Rosengren, also dissented from the majority vote, but they wanted to keep rates steady at 2.00 to 2.25 percent instead of cutting to 1.75 to 2.00 percent. They had also dissented in July, voting to keep the rates steady at 2.25-2.50.

Market participants were not happy. They had already priced in the quarter-point cut and wanted at least some indication of where the Fed is headed in the near future.

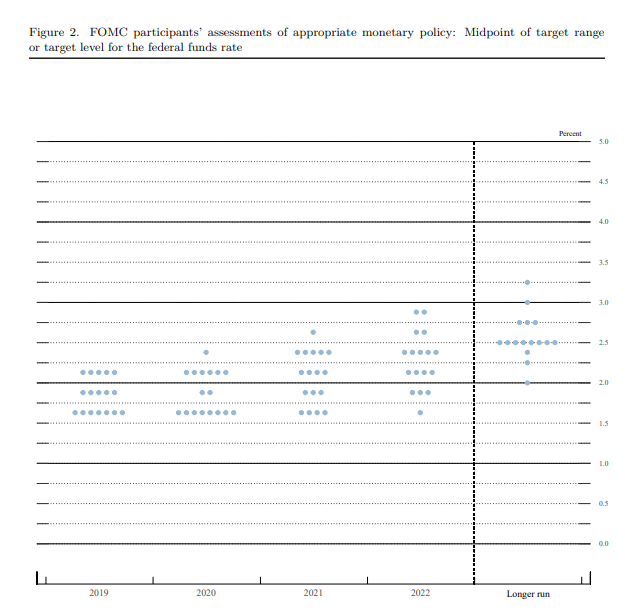

The most they could glean from the dot-plot graph is that seven FOMC members—out of 17 when nonvoters are included—expect one more quarter-point cut this year. Thin gruel indeed, since that leaves 10 policymakers who expect no further cuts.

Stocks plunged, with the Dow shedding 200 points in the wake of the statement.

Equally disheartening is that none of the FOMC members sees rates going below the 1.50-1.75 range through next year. After that, the preponderance shifts to higher rates.

In the vote on Wednesday’s reduction, the board of governors—who all get to vote—fell in line with the chairman’s wishes, as they always do, as did the New York Fed Chief, John Williams, a permanent voter and virtually a member of the board. Fed Chair Jerome Powell got only one other regional bank president, Charles Evans of Chicago, to go along with the Washington consensus.

At the press conference after the decision, Powell responded to a question about a Fed bias toward easing by saying the Fed no longer has a bias. He added that there was no preset course and that policymakers have been willing to shift to a lower path for the Federal funds rate over the course of the year. Nor would it hesitate to shift further to a sequence of rate cuts if the economy went south, but they don’t think it will be necessary.

Coincidentally, overnight markets ran out of money on Monday and the Fed had to inject $128 billion into the markets as the FOMC was meeting so that there was enough to pay taxes and settle bond transactions. It’s the kind of thing that’s not supposed to happen. The last time was in 2008 in the midst of a financial meltdown.

The dates for these transactions were well known in advance. Why, one journalist pointedly asked Powell, didn’t you see this coming. Answer: well, we did see it coming, it was just stronger than we expected.

Powell brushed it off as a technical issue that doesn’t affect the economy or monetary policy, but it’s a type of mishap that lends some credence to President Donald Trump’s constant harping about the Fed’s incompetence.

The New York Fed is responsible for executing monetary policy and the shortage of cash saw rates for Federal funds spike briefly above their 2.25 percent ceiling. No matter how you look at it, the New York bank, under its new head, economist John Williams, dropped the ball in a way it hadn't under his predecessor, Goldman Sachs alum William Dudley.

Powell did say the Fed may have to resume “organic growth” of its balance sheet to make sure there were adequate bank reserves to prevent this type of shortage in the future. He expressly said this would not be quantitative easing, but stocks recovered most of their lost ground because investors view a bigger Fed balance sheet as accommodative no matter how you qualify it.