You know those annoying notifications that chime on your cell phone in the middle of the work day? The ones that sound off to let you know when Kim Kardashian’s daughter sits on a commode? Or when Donald Trump insults a member of the media? I get far too many of those. I’ve tried playing with the notification settings on the apps on my iPhone, but somehow, I still get a ton of unwanted messages.

Last week, I received a notification shortly after the stock market closed shop. The one-liner? “Stocks soar on judgment that Fed will delay rate hike.”

Let that sink in for a moment. Stocks are not rocketing because investors are confident about corporate profitability or sales. They’re not climbing due to jobs optimism or economic acceleration. The Dow moved higher for seven consecutive trading sessions (through Monday 10/12) because – in spite of seven years of 0% overnight lending rates – the U.S. economy is still too weak for a token tightening gesture.

No doubt about it. This is not the 80s or the 90s anymore.

Years ago, money managers, institutional traders and the overall investment community owned stock assets because public corporations were likely to grow their businesses in a strong U.S. expansion. Now? Investors own equities because the “no-go” economy still requires unimaginably cheap credit.

So what’s the big deal about leaving interest rates so low for so long? One reason is excess speculation. For example, plenty of folks own Netflix (O:NFLX) and they have enjoyed a number of years of extraordinary price gains. More recently, however, folks have leveraged account values in order to own even more shares of NFLX. Just as homeowners in 2005 used cash-out refinancing to acquire additional properties with negligible down payments, NFLX shareholders have used rising account values in margin accounts to buy more NFLX stock. As shares of the media giant rise – as NFLX begins looking like a no-lose proposition – speculators employ more leverage to acquire even more shares of NFLX. And why the heck wouldn’t you borrow to buy more? The Fed’s going to make sure that stocks won’t fall, right?

Borrowing money for the purpose of leveraging a stock position is known as margin debt. It has been a profitable venture for anyone who arrived early at the reflated asset price party.

Of course, parties eventually end. Those who overstay their welcome or who arrive late will will find themselves nursing monstrous losses.

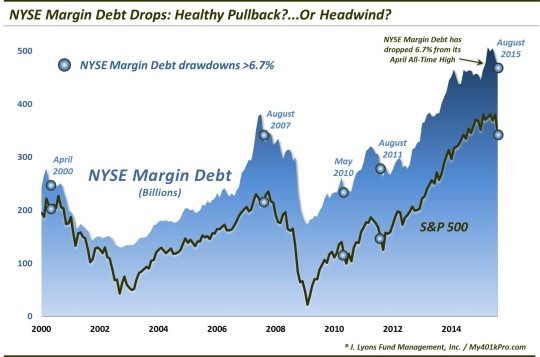

Consider the fact that NYSE margin debt cracked at an all-time high near the $500 billion mark in April. By September, margin debt sank 6.7%, down to $473 billion. Why might this matter? There have only been four times since the turn of the century when margin debt pulled back by 6.7% or more – April 2000, August 2007, May 2010 and August 2011. Those are some relatively inauspicious dates.

Granted, 2010 turned out to be a short-lived correction in the early stages of the current bull market. The other three occasions – the dot-come tech wreck, the worldwide financial collapse and the euro-zone crisis – resulted in massive drawdowns for world stock benchmarks.

Margin debt deterioration is, of course, deleveraging within the stock market. Not only does it signal a lack of confidence that the borrowing-to-buy game can continue indefinitely, but significant declines in markets themselves trigger margin calls that, ultimately, force the sale of the underlying assets.

Now let’s revisit shares of Netflix. Margin debt is a function of the underlying “collateral.” Forced liquidation subsequently reduces the value of the collateral (NFLX), which triggers still more margin calls and additional liquidation. The exact forces that push a high-flyer to incredible heights can send it plummeting 20,000 leagues beneath sea level. (Note: My intent is not to pick on Netflix; rather, I am highlighting how leverage often destroys the best laid plans.)

How enthusiastic have speculators been relative to actual economic activity here in the fall of 2015? Margin debt as a percentage of GDP is close to 3%; in the fall of 2000 and in the fall of 2007, margin debt-to-GDP hit 2.4% and 2.3% respectively.

And it’s not just margin debt that suggests leverage is hitting obscene levels. According to recent research conducted by McKinsey, total debt (consumer, business, government, financial) as a percentage of GDP has surpassed the extremes of 2007: 286% versus 269%. $57 trillion of fresh debt across 7 years at a rate of 5.3%, far outpacing the 2.2% growth in GDP. As my daughter might inquire, “Who’s gonna pay for that?”

Optimists say that when consumers use their credit cards at H&M, when drivers take out auto loans for Audis, when students acquire loans for their $40,000-per-year education, the activity shows confidence in the future. And after all, they tell us, the ability to service the debt is all that matters.

On the other hand, if debt is expanding at a faster rate than economic activity, will the day not come when the expansion of that debt surpasses the ability to service it? If consumer credit as a percentage of GDP was insanely high at 17.5% leading into the financial meltdown circa 2007, how are people better off when it is at 19.5%? Or should we simply assume the Federal Reserve will be able to keep borrowing costs near historic lows forever?

Debt cannot increase indefinitely. Like an economy itself, expansion gives way to contraction. There are credit cycles just as sure as their are business cycles.

We should not be surprised, then, that the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the German finance minister have all warned about extremely high debt ratios the world over. Each have used terms like “dangerous over-leveraging” and “credit panic,” while simultaneously fretting a global financial system that would be vulnerable to any amount of monetary tightening by the U.S. Federal Reserve. Can you say, “Catch 22?”

One way or another, debt extremes eventually give way to deleveraging. And while it is certainly possible that the Fed can deftly maneuver in the near-term – prompting the federal government as well as American businesses, consumers and market speculators to keep borrowing freely – longer-term investors need to be more vigilant.

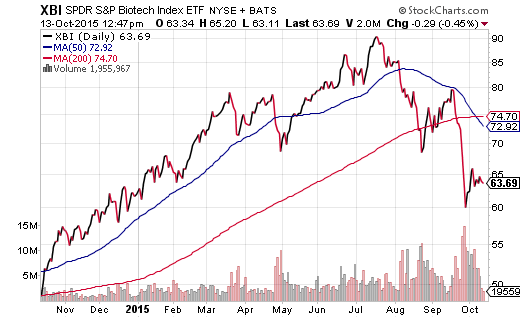

In essence, one’s equity component should focus on low volatility and quality at this juncture. Consider iShares MSCI USA Quality Factor (N:QUAL) and/or iShares USA Minimum Volatility (N:USMV). If you’re going to own individual securities, even in a downturn, you will want to think in terms of low leverage companies like Costco (O:COST) and less volatile corporations like Pepsico (N:PEP). What’s more, you may want to resist the temptation in thinking that the worst is over for previous momentum standouts like the SPDR S&P Biotech (N:XBI).

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (”blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at he ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.