As our editor said last week, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, an apt phrase for the events unfolding in China this week.

Regulators were obliged last year to relax tight controls over the currency in order to qualify for Reserve Currency status from the International Monetary Fund for the yuan/renminbi but had probably not foreseen the consequences. Indeed, many are still not seeing the collapse of share prices on the Shanghai Stock Exchange this week as a currency-related issue.

If You’re an Investor, It’s YOUR Money Getting Purposely Devalued

Anyone holding shares or a pension will be painfully aware that some $2.5 trillion has been wiped off the value of global equities this week, in just four days, events starting in China have rippled around the world causing one of the worst starts to the year for stock markets since the 1980’s.

On the Shanghai market, trading was stopped on Monday as “circuit breakers” closed the market after shares plunged 5% and, again, Thursday trading was canceled for the day after just 29 minutes when the CSI300 fell more than 7%.

Under the “circuit breaker” system, created after the plunge in shares last August, if an index rose or fell 5%, trading was halted for 15 minutes. If it dropped by 7%, trading stopped for the rest of the day.

So what prompted the sell-off? Many have been saying the Shanghai market is a bubble waiting to burst for quite some time, but is it a sudden epiphany among investors that prices are overvalued? No. Actually, it has little to do with share prices and a lot more to do with currency and ill-judged rules imposed by Beijing to try to control the market, Beijing’s actions often have unforeseen consequences in such situations.

What is the Real Value of a Controlled Currency?

First, the currency: as we mentioned above Beijing allowed the yuan to respond more readily to market forces. We won’t say float, but the trading bands were widened and the currency has fallen for much of 2015 against the rising dollar. This got investors worried, even if the Shanghai market was not shaky, a falling currency makes shares less valuable over time.

Further, holders of yuan,companies and investors made up of China’s rising middle and wealthier classes, see the cost of foreign investments such as houses, land, companies, rising almost daily in yuan terms.

Valuation of the yuan moved to a basket of currencies last year rather than a loose peg against the dollar with the promise by Beijing that it would remain more stable against the China Foreign Exchange Trade System basket. That was December, since then the currency has slid for three straight weeks and the central bank has burned through $140 billion trying to defend it.

Falling Production Data Adds to the Misery

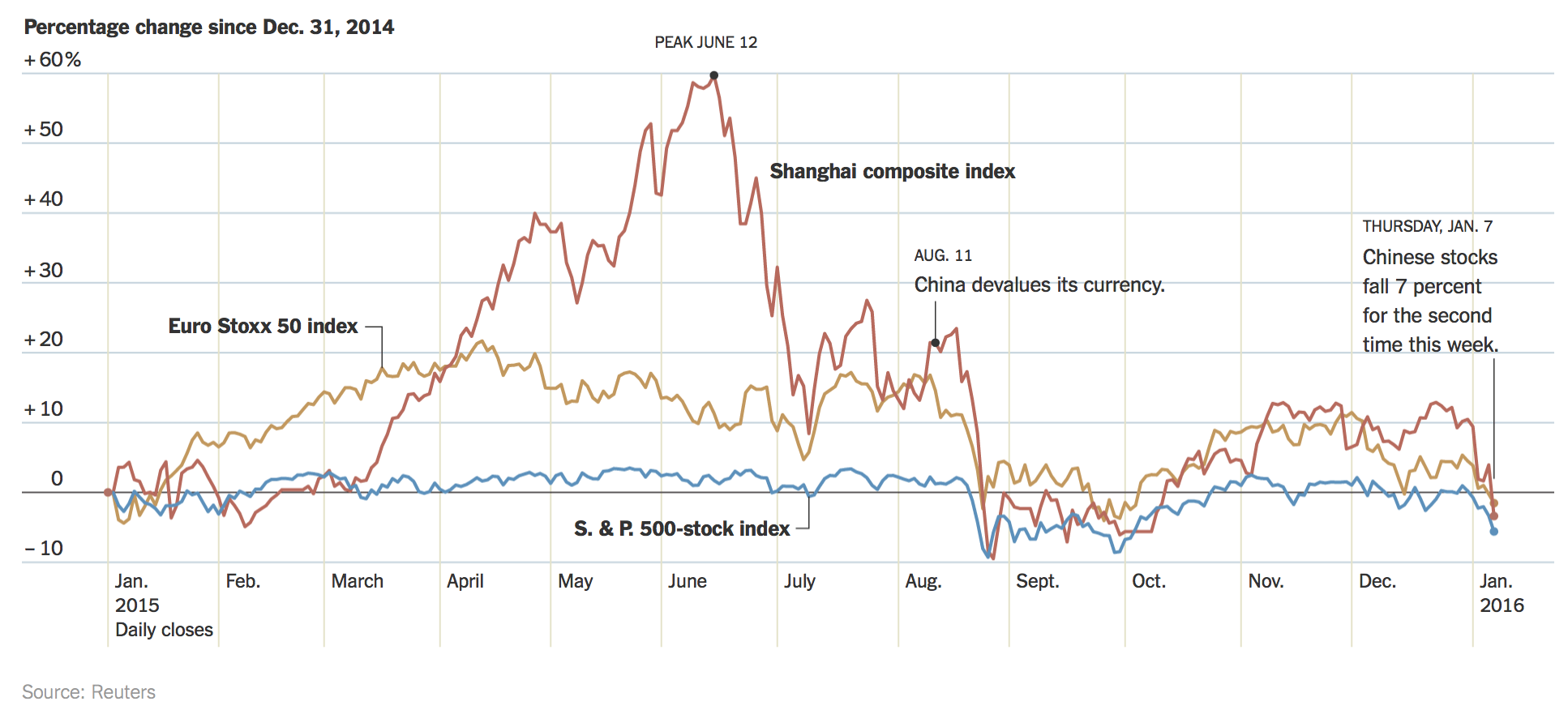

Combine that with a fall in China’s Purchasing Managers’ Index composite for both manufacturing and services to below 50 and frightened investors took flight, dumping shares in a repeat of what we saw last August after Beijing’s snap devaluation of the yuan as this graph from the New York Times illustrates.

Source: The New York Times

In an attempt to calm the panic selling, Beijing has actually made matters worse. The end of a share sale ban, that was imposed last year wherein investors were prohibited from selling for a lock-in period, was extended. Believing they were going to continue to be locked in to shares that were falling in value and, naturally, becoming spooked by company insiders selling shares, investors rushed for the exits. Beijing then had to move fast to extend the ban into 2016, which has helped calm markets temporarily but done nothing the address the underlying causes.

China’s reserves have dwindled from $4 trillion to $3.33 trillion last year and are not far from the $2.6 trillion deemed to be the prudent threshold by the IMF, given China’s $1.2 trillion in liabilities, according to the Telegraph.

A Fragile System Falters

Indeed, coming so soon on the heels of August’s rout, the fragility of the system is becoming worryingly clear. This prompted Mark Williams, of Capital Economics to say to the Telegraph that capital outflows from the country have reached systemic proportions and “There is certainly a sense that the situation is spiraling out of control.”

Global markets are acutely sensitive to the any sign that China might be forced to abandon its defense of the yuan, yet the gradual weakening against the dollar, in particular, is causing a capital flight, exactly what they wanted to avoid. Meanwhile, in unregulated Hong Kong the yuan is being sold by traders at well under the official rate adding further downward pressure on Beijing’s official rate.

As the every prescient Economist put it this week, burdened by the mountain of debt that it has accumulated over the past decade, China needs to begin deleveraging.

That, in turn, means tolerating slower growth. At least for a while. Instead, all indications are that the government will set its annual growth target at 6.5% for the next five years in a plan to be unveiled in March. That is above what most analysts think it can credibly achieve without piling on yet more debt and bringing it closer a real economic crisis. China has reached a point in its development where it needs to move faster in ceding power to the market — power over shares, its currency and the growth rate.

Unless the government gives up more control now, it risks someday losing it altogether.