Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell aims to try and on Tuesday expressed confidence that the central bank will aggressively persist in its quest to resolve its biggest inflation challenge in four decades.

“If that involves moving past broadly understood levels of neutral [interest rates] we won’t hesitate to do that,” Powell told The Wall Street Journal yesterday. “We will go until we feel we’re at a place where we can say financial conditions are in an appropriate place, we see inflation coming down.”

Emphasizing the Fed’s intention, he insisted that “there won’t be any hesitation about that.”

Estimating neutral rates—a level that supports growth while effectively combating inflation—is a mix of art and science. There are many models that attempt to guesstimate this rate and, not surprisingly, results vary by more than a trivial degree.

The Fed’s recent estimates point to a neutral rate in the 2%-to-3% range, sharply higher than the current 0.75%-to-1.0% Fed funds target rate.

The Fed’s hawkish pivot is now complete, at least rhetorically. But that still leaves a couple of key uncertainties to wrestle with in the weeks and months ahead.

First, what exactly does the Fed’s commitment entail in terms of how long it will tighten policy? Will it truly raise rates to combat inflation for as long as it takes, even to the point of pushing the economy into recession to do the heavy lifting?

Powell seems to be on board with this medicine, even to point of recently invoking the name of Paul Volcker, a former Fed Chair who sharply hiked rates in the early 1980s to kill inflation, albeit at the cost of two recessions in the first half of that decade.

But earlier this month, Powell appeared to pull back from expectations that he would go full Volcker.

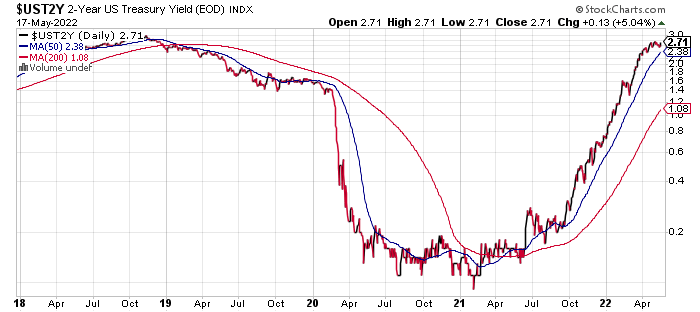

The other big question is how will the bond market price in expectations for the Fed’s monetary plans from this point forward? Although interest rates have shot up in recent months, the market appears to be reassessing how far rates can rise from current levels.

A key variable in the calculus is slowing economic growth. As rates rise, the odds of economic contraction may increase in the current climate if the central bank goes too far too fast with policy tightening.

Although second-quarter economic activity appears to be staging a rebound from the contraction in Q1, a number of economists are predicting that recession risk is rising.

Perhaps sensing this shift, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield has recently pulled back after topping 3% earlier this month for the first time since 2018.

The policy-sensitive 2-year rate—widely seen as a proxy for expectations on Fed policy—has also paused in recent days after an extended run higher.

Fed funds futures are currently estimating an 87% probability that the Fed will raise rates again by 50 basis points to a 1.25%-to-1.50% target range at the June 15 FOMC meeting.

Beyond that point, the outlook turns murky, in no small part due to uncertainty about how the economy reacts to higher rates and what the change implies for Fed policy.

Powell’s comments yesterday imply that the Fed will err on the side of breaking inflation’s momentum, which suggests that the central bank will tolerate more deterioration in economic momentum than recently expected.

“The Fed will tighten financial conditions until it sees clear and compelling evidence that the economy is on a path to price stability,” advises Tim Duy, Chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors, in a note to clients on Tuesday. “The Fed knows that path may require a recession.”

The main variable that will determine how all this plays out is the path of inflation in the near term. Consumer prices for April showed an easing in the annual pace—the first softer print since last August, the 8.3% year-over-year increase continues to show inflation running hot.

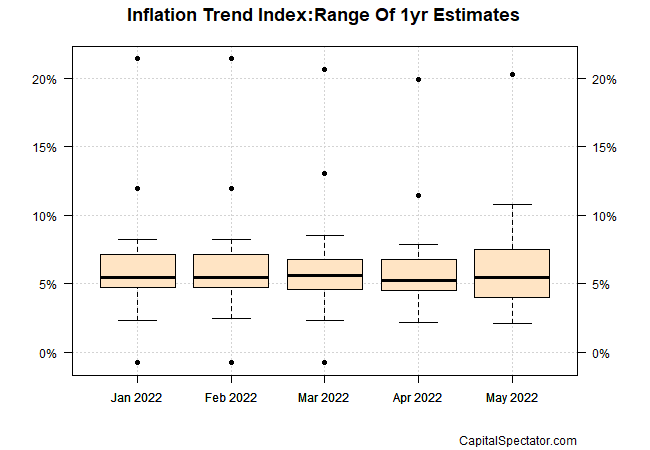

CapitalSpectator.com’s Inflation Trend Index (ITI), a multi-factor estimate of pricing pressure, suggests that May doesn’t look set to offer much, if any, relief. ITI’s median estimate for this month ticked up to 5.4%, reversing (slightly) the downturn in April.

What is clear is that the Fed now appears committed to reducing inflation. “What we need to see,” Powell explained yesterday, “is clear and convincing evidence that inflation pressures are abating and inflation is coming down. And if we don’t see that, then we’ll have to consider moving more aggressively. If we do see that, then we can consider moving to a slower pace.”