The Bank of International Settlement asks in its quarterly report if there has been "a paradigm shift in the markets?" Although it does not provide an explicit answer, it does argue that there has been a significant change in sentiment. The chart of the US 10-year yield, created on Bloomberg, depicts the 35-year decline in US yields. The recent rise in yields can be seen, but there have been other counter-trend increases in the past.

The BIS notes that after falling to new lows, overall yields jumped dramatically by the end of November. The rise in yields was comparable to the taper tantrum in May-September 2013.

The key change, according to the BIS, was the U.S. election. It recognizes that until then, assets in the emerging-market economies seemed unperturbed by the developments in the advanced economies, even though U.S. bond yields were 50 bp off their lows by the time of the election in early November.

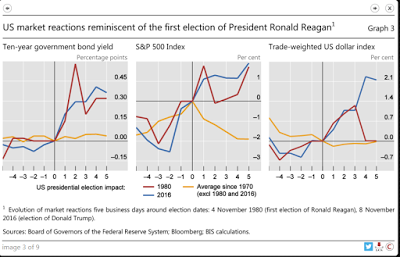

The election prompted a marked change in expectations. The BIS notes that investors are now anticipating expansive fiscal policy, lower corporate taxes, easier regulation and a boost to corporate profits. Indeed, as this BIS graphic shows, the apt comparison is to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. The rise in yields and S&P 500 since the U.S. election are broadly similar to 1980, while the dollar's rally has been stronger.

Our approach focused on the policy mix. The best policy mix for a currency is tighter monetary and looser fiscal policies. We thought regardless of the election outcome that the policy mix would become more favorable for the dollar. Both candidates promised fiscal stimulus and Trump's campaign promises were bigger, not only than Clinton's pledges, but Sanders' as well.

Monetary policy had already begun to normalize, albeit extremely slowly, though the commitment is there. The direction of monetary policy was clear prior to the election and end of the inventory and capex-led headwinds saw the U.S. economy return to above-trend growth. Although fiscal policy may expand as much as it did during Reagan's first term, monetary policy is unlikely to match what Volcker did for the simple reason that the starting point for inflation is diametrically different.

Perhaps blunting this in part is the divergence in the interest-rate cycle between the U.S. on one hand and nearly all of the major economies on the other. The U.S. 10-year premium over Germany is the widest since 1997. The U.S. 10-year premium over Japan is at six-year highs. The U.S. 10-year premium over the UK is near 16-year highs.

The BIS appears relatively relieved that the sharp rise in core yields was fairly orderly if sharp. It notes that corporate spreads remained tight in contrast to the taper-tantrum experience. In the run-up to the election, corporate spreads narrowed and were near their lows for the year at the end of November. Corporate spreads widened a little in Europe, though they were around a fifth lower than experienced immediately after the UK referendum.

In seeking to explain the limited impact of the higher yields, the BIS suggests that the major holders of U.S. Treasuries no longer bear mark-to-market risks, while there is less ripple effect from hedgers. These are the direct consequences of official action. Specifically, around 40% of the U.S. Treasury market is in the hands of the Federal Reserve and other foreign central banks. In the past, a rise in Treasury yields would spur hedging from the likes of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This contributed to past bond-market turbulence. However, as is well appreciated, Fannie and Freddie sold a large share of their portfolios to the Federal Reserve, which does not hedge its securities.