Add BlackRock’s CEO to the list of high-powered people in finance who are skeptical that a flattening yield curve reflects a threat that’s brewing for the US economy. Although a narrowing spread between short and long Treasury rates has been a warning sign in the past, this time is different, said Larry Fink, head of the world’s biggest money manager.

Fink told Yahoo Finance editor-in-chief Andy Serwer on Thursday:

“I believe the flattening of the yield curve is indicating to me that we still have record pools of cash,”

He notes that the wide differential in Treasury rates in the US vs. German and Japanese yields is “keeping the yield curve flatter than normal. I don’t believe it has any indication of a recession. And I think it’s just the dynamism of global markets.”

His comments appear to mark an evolution in the CEO’s interpretation of the yield curve as a macro indicator. Last October, Fink said that the narrowing between short and long rates was a development that the central bank should monitor. “If there is a risk, it’s that. I hope the Federal Reserve pays attention,” he advised.

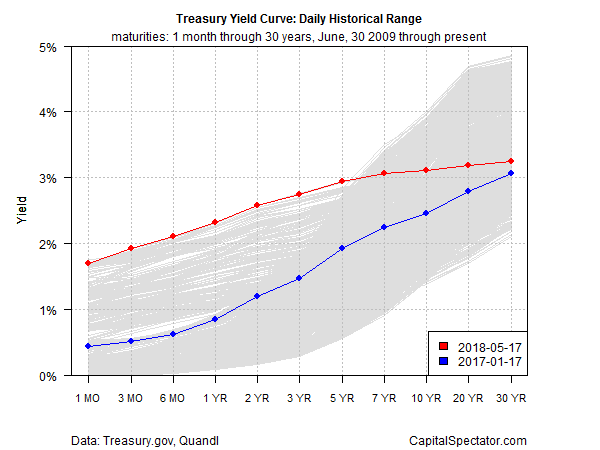

The current US 10-Year rate is 3.10%, far above the 0.62% rate for the equivalent government bond in 10-year and the 0.05% 10-year rate in Japan, according to Bloomberg data in early trading on Friday (May 18).

Fink’s latest comments echo recent remarks by the Federal Reserve chairman. Speaking at a press conference in March, Jerome Powell questioned the value of the Treasury yield curve as a tool for predicting the next US recession. Cleveland Federal Reserve President Loretta Mester has also cast doubt on the recent flattening of the yield curve as a sign of rising recession risk.

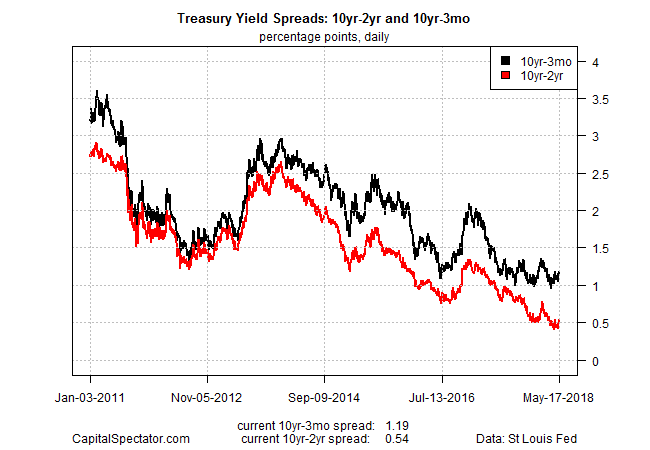

The historical case for watching the yield curve as an early sign of macro trouble is reasonable, based on the fact that recessions have usually followed when short rates rise above long rates. By that standard, however, there’s room for debate about business-cycle risk because the yield curve is still positive, although it has narrowed sharply over the past year. The widely followed spread for the 10-year-less-2-year rate, for instance, was a thin 54 basis points yesterday (May 17), which is close to the smallest gap in 11 years.

If and when the yield curve inverts, the shift will be interpreted by some, perhaps most economists as a warning that a new recession is imminent. Note, however, that a research note published by the New York Fed advised that “inversions in daily or intraday data often prove to be false signals. Inversions observed over longer periods—at a monthly or quarterly average frequency—provide more reliable signals.”

Monitoring recession risk by way of a wider mix of economic indicators beyond the yield curve is arguably even better, not to mention essential if the analysis recently espoused by Fink, Powell and Mester is correct.

In any case, the yield curve is still positively sloped and so a formal recession warning from this data has yet to arrive. If the spread turns negative at some point, Fink is among a small chorus of voices telling us that the indicator has lost its power to predict business-cycle risk. Maybe, but deciding if that’s a genuinely wise piece of analysis should rely on broader economic context. No one data set should be assumed to be flawless. The economic trend overall, by contrast, comes with far less baggage.