Just recently my friend Cullen Roche wrote a great piece entitled, Can we All Agree to Stop Comparing Everything to the S&P 500, in which he stated:

"Benchmarking is a pernicious thing in financial circles. Not only because it disconnects the way the client and a fund manager understand the concept of 'risk', but also because the concept of benchmarking seems to be misunderstood."

Risk is rarely understood by investors until it is generally too late. Take, for example, a call I received the other night during a broadcast of the "Lance Roberts Show." The caller didn't understand why people didn't just buy an S&P 500 index and then just leave it alone. When I asked him when he started investing he proudly stated that he had been investing for the almost 5 years and had more than doubled his money. The problem is that this particular individual has no functional idea of what "risk" entails.

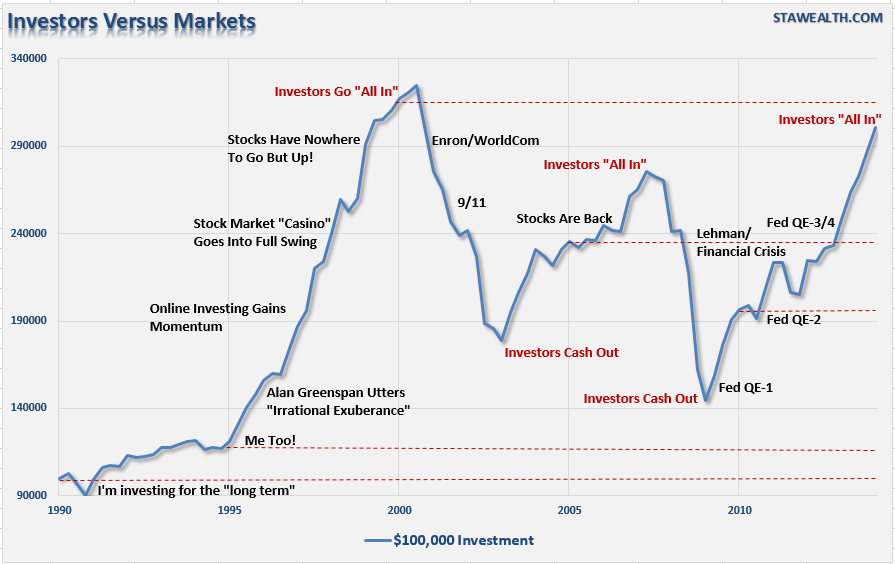

The chart below is an inflation adjusted return of $100,000 investment in the S&P 500 from 1990 to present. The reason that 1990 is important is because that is when roughly 80% of all investors today begin investing. Roughly 80% of those began after 1995. If you don't believe me, go ask 10 random people when they started investing in the financial markets and you will likely be surprised by what you find.

As shown, there is certainly a case to be made for buying and holding an index. However, it is quite clear that "buying low" and "selling high" would have been much more beneficial from 2000 until present.

Unfortunately, the reality is that investors rarely do what is "logical" but react "emotionally" to makret swings. When stock prices are rising instead of questioning when to "sell" they lured in near market peaks. The reverse happens as prices fall leading first to "paralysis" and "hope" that losses will soon be recovered. Eventually, near market bottoms the emotional strain is too great and investors "dump" shares at any price to preserve what capital they have left. Despite the media's commentary that "if an investor had 'bought' the bottom of the market..." the reality is that few, if any, actually did. The biggest drag on investor performance over time is allowing "emotions" to dictate investment decisions. This is shown in the 2013 Dalbar Investor Study, which showed "psychological factors" accounted for between 45-55% of underperformance. From the study:

"Analysis of investor fund flows compared to market performance further supports the argument that investors are unsuccessful at timing the market. Market upswings rarely coincide with mutual fund inflows while market downturns do not coincide with mutual fund outflows."

In other words, investors consistently bought the "tops" and sold the "bottoms." The other two primary reasons of underperformance from the study related to a lack of capital to invest. This is also not surprising given the current economic environment.

There are many reasons why you can't really beat the S&P 500 index over time and why you see statistics such as "80% of all fund underperform the S&P 500." The impact of share buybacks, substitutions, lack of taxes and trading expenses all lead to outperformance by the index over everyone else that is actually investing and doesn't receive those benefits. Furthermore, any portfolio that is allocated to to lower volatility, create income or provide for long term financial planning and capital preservation will underperform the index so comparing your portfolio to the S&P 500 is "apples to oranges." Cullen makes this point very clearly:

"But it gets worse. Often times, these comparisons are made without even considering the right way to quantify “risk”. That is, we don’t even see measurements of risk adjusted returns in these “performance” reviews. Of course, that misses the whole point of implementing a strategy that is different than a long only index.

It’s fine to compare things to a benchmark. In fact, it’s helpful in a lot of cases. But we need to careful about how we go about doing it."

I recently wrote a fairly deep study on the perils of benchmarking and why, despite your best intentions, it was highly unlikely that you will ever "beat the market" over the long term.

"While Wall Street wants you to compare your portfolio to the "index" so that you will continue to keep money in motion, which creates fees for Wall Street, the reality is that you can NEVER beat a "benchmark index" over a long period. This is due to the following reasons:

1) The index contains no cash

2) It has no life expectancy requirements -- but you do.

3) It does not have to compensate for distributions to meet living requirements -- but you do.

4) It requires you to take on excess risk (potential for loss) in order to obtain equivalent performance -- this is fine on the way up, but not on the way down.

5) It has no taxes, costs or other expenses associated with it -- but you do.

6) It has the ability to substitute at no penalty -- but you don’t.

7) It benefits from share buybacks -- but you don’t."

For all of these reasons, and more, the act of comparing your portfolio to that of a "benchmark index" will ultimately lead you to taking on too much risk and ultimately making emotionally based investment decision making. The index is a mythical creature, like the Unicorn, and chasing it takes your focus off of what is most important -- your money and your specific goals. Investing is not a competition and, as history shows, there are horrid consequences for treating it as such. So, do yourself a favor and forget about what the benchmark index does from one day to the next. Focus instead on matching your portfolio to your own personal goals, objectives, and time frames. In the long run you may not beat the index, but you are likely to achieve your own personal investment goals which is why you invested in the first place.