Just recently it was announced that the Dow Jones Industrial Average will undergo some changes as three companies are removed (Bank of America, Alcoa and Hewlett-Packard) to be replaced by Goldman Sachs, Nike and Visa. However, the reality is that, while the changes are of interest to financial analysts and market hobbyists, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is no longer relevant as a representation of America's industrial complex or most individual portfolios. One of my favorite writers, Neil Irwin, recently wrote in the Washington Post:

The announcement of the changes shows the absurdity of the index. 'The index changes were prompted by the low stock price of the three companies slated for removal and the Index Committee's desire to diversify the sector and industry group representation of the Index,' the company said.

Of course, the per-share price of a stock has absolutely nothing to do with its size, importance or representativeness. Bank of America is being booted, it would seem, for its sub-$15 per-share price, in favor of Goldman Sachs with a $164 share price. But Bank of America is a way bigger company! Its total market capitalization is $155.6 billion, to $74.5 billion for Goldman. It has 257,000 employees, to 32,000 for Goldman. It is engaged in banking and lending activity in basically every community in America, as opposed to Goldman's specialty investment banking business. But when you find yourself in the archaic trap of weighing companies based on their per-share price, that's the kind of absurdity you end up with.

However, these changes highlight a much bigger issue to investors. I recently wrote an article entitled "Why You Can't Beat The Index", which covered the variety of flaws of how benchmark indexes are calculated and the effect on portfolios.

The sad commentary is that investors continually do the wrong things emotionally by watching benchmark indexes. However, what they fail to understand is that there are many factors that affect a 'market capitalization weighted index' far differently than a 'dollar invested portfolio.'

Specifically I covered the impact of the "substitution effect" on the index and the inherent "replacement effect" on your portfolio. The upcoming changes to the Dow Jones Industrial Average highlight the importance of these effects on portfolios that are benchmarked to an index.

In order to demonstrate this particular issue, we have to make some assumptions. Most investors don't generally build a "price-weighted" portfolio, which is a major flaw of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, but rather build portfolios by either buying round lots or investing rounded dollar amounts.

For our example we will assume that an individual invests a total of $300,000 dollars equally into each of the 30 stocks that comprised the Dow Jones Industrial Average as of November 1, 2005. Furthermore, the portfolio will be managed exactly like the index and will only be changed when changes to the index are made. (For purposes of this example only capital appreciation will be utilized.)

Here is where the problems begin. On February 19, 2008, just prior to onset of the financial crisis, the good folks at S&P Dow Jones indices swapped out Honeywell and Altria for Bank of America and Chevron. In hindsight, I am quite sure that the decision to replace Honeywell with Bank of America was regretted considering what happened next. However, the important point is that when the two issues were swapped out, there was no change to the underlying value of the index due to the way it is calculated.

However, the portfolio experienced a significant negative impact. In order to adjust the portfolio, the shares of Honeywell and Altria had to be sold and then new shares of Bank of America and Chevron had to be purchased. The original $10,000 investment into Honeywell had grown to $13,367 but the same investment in Altria had fallen to just $2,275. Therefore, since there was a net loss of $4,358 between the two positions, only $15,642 was able to be reinvested in the two new companies.

In September of 2008 it was American International Group's turn to be swapped out for Kraft Foods. While this swap again didn't change the value of the index, it resulted in a 95% loss in the sale of AIG in the portfolio.

Then, as the financial crisis ended and the markets began to recover, Citigroup and General Motors were swapped out for Cisco Systems and Travelers in June of 2009. These two swaps resulted in net losses for the portfolio components of roughly 93% and 85% respectively.

The next change came in September of 2012, when Kraft Foods was swapped out for United Healthcare. Once again there was no change to the value of the index, but the impact to the portfolio was at least positive this time showing a 20% component gain.

The most recent changes do not actually occur until September 20, 2013, but for the sake of illustration we will assume that the announced changes occurred as of the close on September 11th. Therefore, the substitutions of Nike, Goldman Sachs and Visa resulted in portfolio losses of roughly 69% in Alcoa, 66% on Bank of America and 17% for Hewlett-Packard.

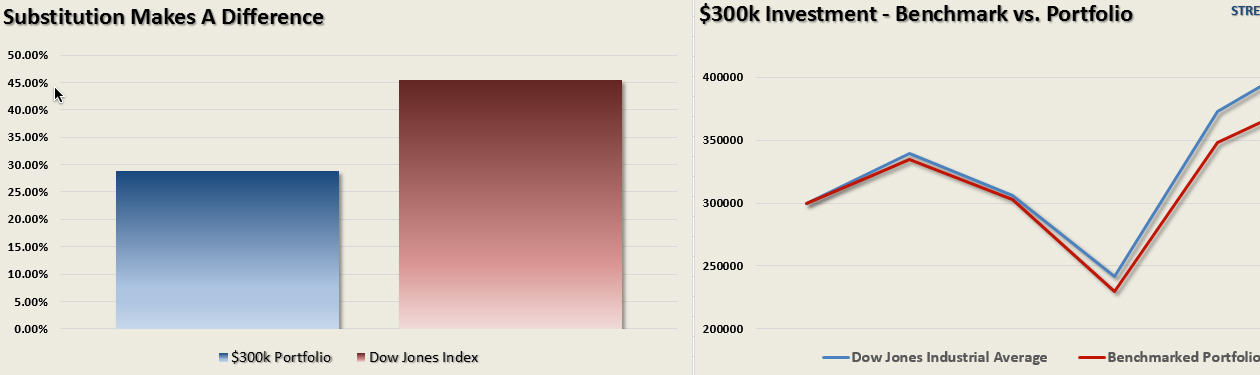

The following two charts show you the difference in returns from $300,000 invested in the index versus a portfolio benchmarked to the index.

This is the impact of the "substitution and replacement" effects. During the period of the analysis the drags created by the loss of capital in the portfolio resulted in a net return difference of 28.85% versus 45.54% for the Dow Jones index. This effect is magnified over longer periods of time.

While Wall Street wants you to compare your portfolio to the "index" so that you will continue to keep money in motion, which creates fees for Wall Street, the reality is that you can NEVER beat a "benchmark index" over a long period. This is due to the following reasons:

- The index contains no cash

- It has no life expectancy requirements - but you do.

- It does not have to compensate for distributions to meet living requirements - but you do.

- It requires you to take on excess risk (potential for loss) in order to obtain equivalent performance - this is fine on the way up, but not on the way down.

- It has no taxes, costs or other expenses associated with it - but you do.

- It has the ability to substitute at no penalty – but you don't.

- It benefits from share buybacks – but you don't.

In order to win the long term investing game, your portfolio should be built around the things that matter most to you.

- Capital preservation

- A rate of return sufficient to keep pace with the rate of inflation.

- Expectations based on realistic objectives. (The market does not compound at 8%, 6% or 4%)

- Higher rates of return require an exponential increase in the underlying risk profile. This tends to not work out well.

- You can replace lost capital

- but you can't replace lost time. Time is a precious commodity that you cannot afford to waste.

- Portfolios are time-frame specific. If you have a 5-years to retirement but build a portfolio with a 20-year time horizon (taking on more risk) the results will likely be disastrous.

The index is a mythical creature, like the Unicorn, and chasing it takes your focus off of what is most important -- your money and your specific goals. Investing is not a competition and, as history shows, there are horrid consequences for treating it as such. So, do yourself a favor and forget about what the benchmark index does from one day to the next. Focus instead on matching your portfolio to your own personal goals, objectives, and time frames. In the long run you may not beat the index but you are likely to achieve your own personal goals, which is why you invest in the first place.