I recently ate dinner with a high-net-worth sales executive who asked me, “What are your thoughts on Amazon?” I told him the truth. Excellent company…unusually vulnerable stock. I explained my thesis on debt levels, excessive financial leverage, bubbly market euphoria, over-valuation as well as forced liquidation via margin calls.

He seemed surprised that I might be concerned. He stated confidently, “Jeff Bezos is a one-of-a-kind innovator and Amazon is the future of retail. The stock should do very well over the next decade.”

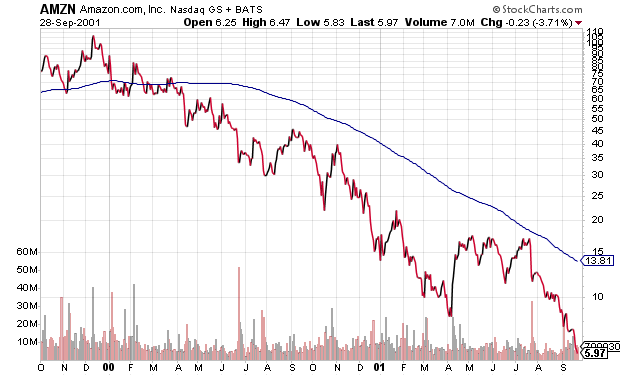

I knew better than to debate the issue. People have short memories. They find reasons why 2000 and 2008 are not relevant in today’s world. So I was not about to call up the following chart of Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN) on my iPhone.

Again, I think Amazon is an extraordinary company. Yet its stock price will not care what anyone thinks when margin call deleveraging and extreme overvaluation collide. Amazon still fell 94% from its insanely overvalued 1999 high to its ridiculously undervalued 2001 low in the dot-com bubble.

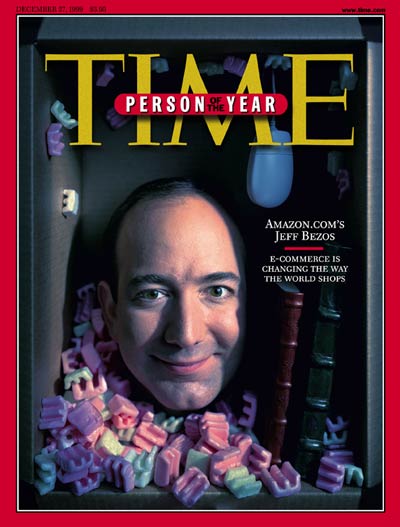

Bear in mind, investors said the same things about the future of online retail as well as the greatness of Bezos in late 1999. In fact, within days of Amazon fetching record prices for its shares, Time magazine crowned Bezos “Person Of The Year.” And the December issue’s byline? E-commerce is changing the way the world shops.

A “hold-n-hoper” should accurately point out that Amazon has experienced nominal gains over any 10-year period. For that matter, if you were smart enough to buy shares a few years earlier than December of 1999, even if you held on for dear life, your current stake might allow you to enjoy the fruits of financial freedom.

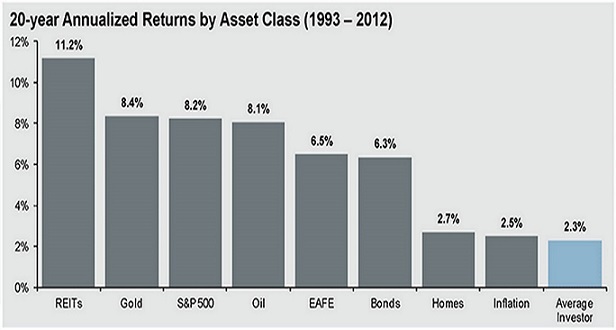

However, the overwhelming majority of people find it next-to-impossible to watch their hard-earned dollars disappearing by the day. They buy Amazon shares at extremely high valuations with the intention of holding for the proverbial long-term. Then, when the fear of losing principal couples with the reality of a reverse wealth effect, they sell shares at attractively priced bargains. Indeed, the famous Dalbar studies demonstrated how most investors buy high and sell low, rather than buy lower and sell higher.

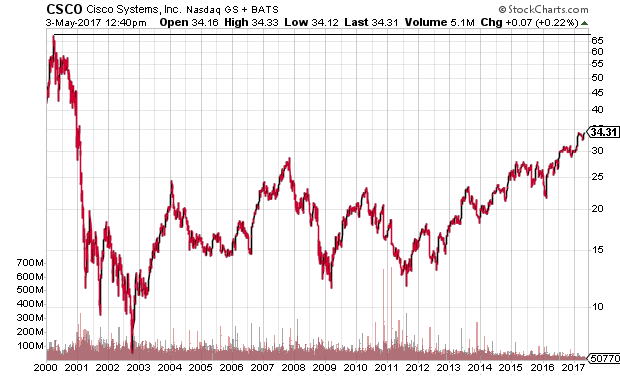

Let me provide another example. The media fawned over another man in 1999 by the name of John Chambers. You may remember the CEO of Cisco Systems (NASDAQ:CSCO) who had affectionately earned the title of “Mr. Internet.” At the turn of the century, Cisco controlled 30% of data networking equipment and as much as 80% of routers. It was also the fastest growing company ever to list on the NASDAQ.

If you were an investor in 1999, you loved this company. By all accounts at the time, Cisco controlled the Internet and CEO Chambers was the gatekeeper.

So should you have loved the stock at record high valuations? Probably not. Cisco shares are still down nearly 50% from a high-water mark near the turn of the century (March 2000). On the other hand, waiting for the crowd to liquidate in abject fear — waiting for undervaluation in a company you love — would have allowed you to acquire shares on the ultra-cheap circa 2001 or 2002.

The wealth effect that the Federal Reserve sought to create with its electronic money creation successfully boosted prominent assets like stocks and real estate. Yet the Fed’s irresponsible continuation of conventional and unconventional policies emboldened groups and entities to borrow excessively at ultra-low rates. It is almost as though zero thought had been given to the risks associated with dangerous debt levels, including the near certainty of a wealth effect reversal.

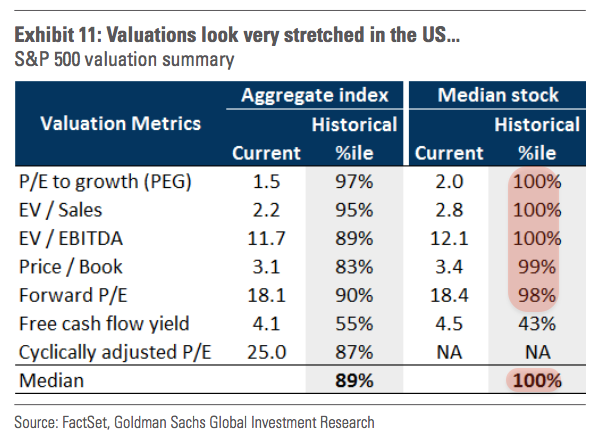

The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (a.k.a. “CAPE” or “PE 10”) for U.S. stocks is at 29. Since the 1870s, there are only two occasions when CAPE was higher: 1929 when it surpassed 32, and in 2000, when the tech balloon sent this measure as high as 44. Meanwhile, on a number of other critical measures, stocks sit in the 100th percentile. That means valuations have never been this exorbitant — ever.

By the way, ultra-low interest rates today do not render valuations as irrelevant. From 1935-1954, the 10-year yields were very similar to what we have witnessed over the last three years. Yet the price “P” that the investment community was willing to pay for earnings “E” or sales “S” still plummeted in four bearish retreats. In other words, low interest rates did not stop four bearish price reversions in the 20-year period — a period that included descents of -49.1%, -23.3%, -40.4% and -23.2% respectively.

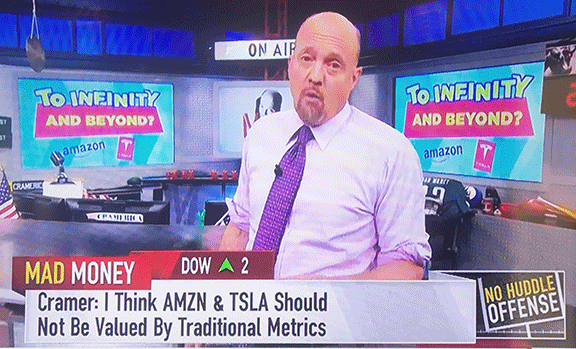

Nevertheless, we still have cheerleaders who will tell you that traditional metrics no longer matter. It is almost as though some media darlings did not get the memo from the year 2000. Amazon to infinity and beyond? Not without a harrowing price descent that will serve up a bargain price on corporate shares first.

I can already anticipate the bullish argument on how corporate tax reform will be the stimulative juice to replace low borrowing cost addiction. Tax rate reductions will repatriate dollars from abroad, not to mention significantly boost the net income for corporations. Perhaps. Assuming Congress passes a meaningful tax package, companies should be able to put forward far better earnings numbers.

Three thoughts. First, it would be my contention that the majority of those tax-related price gains came as a result of the election’s reevaluation of a Trump presidency. Second, the data on corporate tax cuts as they might relate to stock price appreciation are decidedly mixed.

Take a look at the table below. Corporate taxes were an exceptionally modest 14.7% in the 1930s. It did not seem to help stocks as the asset class annualized at a negative rate over the decade (-0.9%). Marginal corporate rates surged to unhealthy peaks in the 1940s and 1950s; stocks soared in spite of higher taxes. Both individual and corporate tax rates fell in the 1960s, 1970, 1980s and 1990s without a definitive pattern, other than a likely boost from the combination of lower interest rates and lower tax rates in the Reagan era.

And this brings me to a third point. For all the hope that corporate tax reform can inflate stock prices even higher than they are right now, the environment for stock gains simply is not as robust as it was for Reagan back in 1982. In Reagan’s time, there was significant room to push the Fed Funds Rate and 30-year mortgages down, helping to stimulate the economy. Not so easy in 2017. In Reagan’s time, the debt levels for households as well as the government were sustainable. Here in 2017, they are entirely unsustainable with even the most modest increases in interest payments.

I am not going to stop you from acquiring more shares of Amazon in May of 2017. Of course, you might want to have a plan for stepping aside should things not go precisely as you hope.

Me? If I am going to buy anything in today’s stock world, it might be a company like Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD). Additionally, we still maintain roughly 50% in high quality equities for moderate growth-and-income clients, down from a more robust 70% widely diversified allocation. If necessary, though, we may reduce stock risk even further, reducing the tactical allocation and/or employing the Multi-Asset Stock Hedge (MASH) Index.