Is the U.S. economy on solid footing? Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen seems to think so. In particular, Yellen expressed confidence in household spending as well as job growth during prepared testimony before Congress on Thursday.

It's not surprising to see central-bank authorities describe current economic circumstances in glowing terms. Later this month, members of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) hope to hike borrowing costs for the first time in nine years.

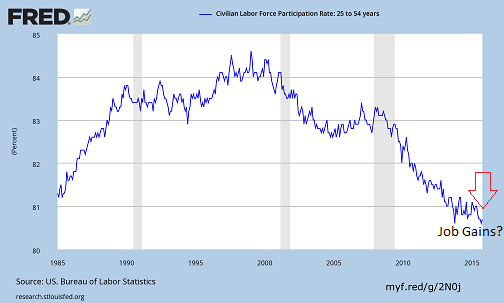

Unfortunately, the U.S. economy may not be in the greatest shape for the Fed to act. For example, while the headline unemployment rate is only 5% – a condition that Yellen describes as close to full employment – the percentage of working-aged Americans (25-54) with a job has not been this low in more than three decades.

Let’s examine the chart above in detail. The 25-54 year old demographic is the prime working-aged sector of the American population. Grammy and grandpa are not the ones who have stopped working entirely; rather, millions upon millions of 25-54 year olds are no longer counted as participants in the workforce. Indeed, when you strip out millions upon millions of working-aged individuals, your headline unemployment rate is going to move lower. Yet that’s not full employment. How can we be close to full employment when 19.3% of 25-54 year old Americans don’t hold a job?

If you want to see genuine job growth, look no further than 1985-1989 and 1995-1999. During those periods, you see the percentage of 25-54 year olds with employment catapulting higher. During a five-year span (1989-1994) that encompassed the early 1990s recession? Jobs were hard to come by. That’s why one can see the flattening of the 25-54 year old demographic at that time. Similarly, one of the reasons that the mainstream media called the 2002-2007 economic expansion a “jobless recovery” was due to the flattening of the labor force participation rate in the 5-year run.

How, then, can Fed committee members express so much confidence about labor-market gains? At best, the chart might be showing signs of a bottoming process, where the new normal is a 19% rate of unemployed Americans (25-54). The rate of decline does appear to have slowed over the last few years. At worst? The pace of declines in the percentage of working-aged individuals who have left the workforce re-accelerates.

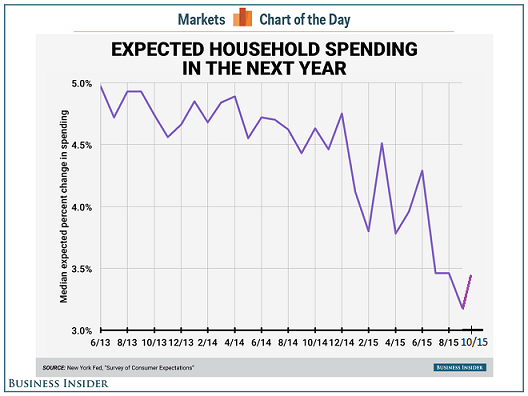

Of course, Yellen did not merely point to labor gains in Thursday’s testimony. She described vibrant household spending in a nod to a service-oriented economy. What are the problems here? For one thing, families are planning to spend less in the coming year. According the New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations, the median household expects its spending to grow a mere 3.47% as of mid-October, which happens to be near its lowest level in the survey’s two year history.

Similarly, the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index fell to 90.4. Not only did the reading on consumer confidence severely miss consensus estimates of 99.5, it was the lowest reading since September 2014. It gets worse. The personal savings rate hit 5.6% in October – the highest level since December of 2012. The combination of higher savings, lower confidence and plans to curtail spending habits hardly supports Yellen’s contention that household spending will be a bright spot.

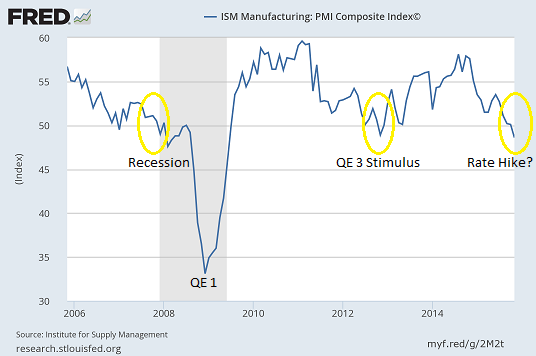

Of course, sometimes what Fed committee members don’t say about the economy is telling as well. Yellen seems entirely unperturbed by the manufacturing sector’s flirtation with recession. That was not the case in 2012 when the Federal Reserve unleashed its boldest stimulus measure to date – a third iteration of quantitative easing affectionately dubbed “QE3.” Then, the prospect of a manufacturing recession mattered. Now it’s irrelevant?

From my vantage point, the manufacturing slide is very relevant. First of all, the more important service-oriented sector will have to demonstrate impressive acceleration to offset the drag of a shrinking manufacturing sector. (The personal savings rate, household spending plans and consumer confidence are not particularly supportive of such an offset.) Second, manufacturer struggles forewarn additional layoffs in high-paying jobs as well as ongoing corporate revenue declines at U.S. multinationals. Demand by foreign companies continues to wane.

Granted, Yellen tried to boost morale when she explained that downside risks from abroad have lessened. Unfortunately, this one does not pass the sniff test. At least one financial institution, Citi, expects China to become the first major emerging market to slash interest rates to zero, precisely because of economic deceleration. Meanwhile, Brazil’s economy shrank by a monumental 4.5% in its most recent reading. The fact that Brazil’s gross domestic product fell by a record 4.5 per cent in its third quarter tells you that Latin America’s largest country is staring down the barrel of one of its worst recessions ever.

Okay, then. The jobs picture is not as rosy as the Fed would have us believe. Neither is household spending. Manufacturing is a mess, while the global economy is under serious pressure. What does it all mean for stock investors?

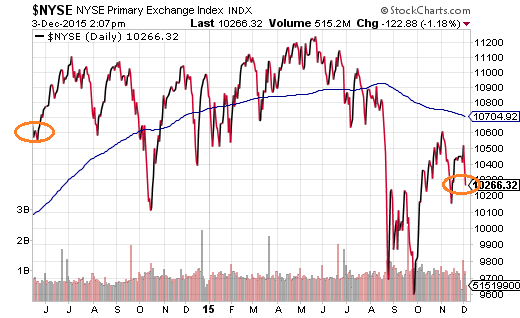

Well, if you believe perma-bull hype, stocks are in phenomenal shape. On the other hand, if you look beyond the S&P 500 – if you examine broader market indices like the (NYSE) index – you have reservations about overexposure to stock risk.

Consider the admonition of billionaire hedge fund manager, David Tepper, in May of 2014. “Don’t be too frickin’ long.” That was 18 months ago. For those who insist that the stock market keeps grinding higher, broader stock market indices suggest otherwise.

The commentary herein, and the caution that I have been expressing since early 2014, has focused on how one should position himself/herself in late-stage bull markets. Long-time readers understand that the majority of my clients still own long-time positions such as Vanguard High Yield Dividend (N:VYM)), SPDR Select Technology (N:XLK)), iShares USA Minimum Volatility (N:USMV) and S&P 500 SPDR Trust (N:SPY). What I have largely proposed over the last 18-21 months is that investors reduce their overall exposure to risk, lightening up on the asset class canaries – small caps, high-yield bonds, commodity-related companies and emerging markets.

In other words, don’t be too freakin’ long.