By Martin Petty

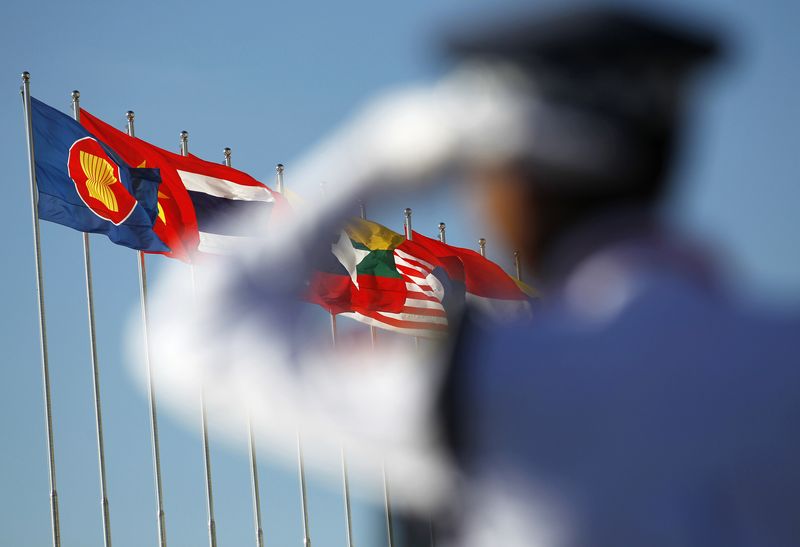

(Reuters) - Foreign ministers from member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are meeting on Thursday to discuss an intensifying crisis in Myanmar, 18 months after agreeing a peace plan with its military rulers.

WHY IS THE MEETING HAPPENING?

ASEAN's peace effort is the only official diplomatic process in play, but it has so far been a failure, with the junta unwilling to implement a so-called "five-point consensus" that it agreed to with ASEAN in April 2021.

ASEAN holds its annual summit next month and will be joined by numerous world leaders. The United Nations has backed the ASEAN plan, but international patience is wearing thin, with suspicion the generals are paying lip service and buying time to consolidate power and crush opponents before a 2023 election, knowing they could then control the outcome.

For ASEAN to remain credible as a mediator, it may need to present a new strategy before the summit.

WHAT IS THE CONSENSUS?

The agreement includes an immediate end of hostilities, all parties engaging in constructive dialogue, allowing an ASEAN envoy to mediate and meet all stakeholders, and for ASEAN to provide humanitarian assistance.

So far, the only success cited by ASEAN chair Cambodia has been allowing some humanitarian access, but that has been limited and conditional.

WHAT HAVE THE SPECIAL ENVOYS DONE?

ASEAN has had two Myanmar special envoys and both have expressed frustration with the junta for denying them access to other stakeholders, including deposed leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who is on trial, accused of multiple crimes.

The junta has refused to engage opponents or civil society groups and has outlawed a shadow National Unity Government (NUG) and an alliance of sidelined lawmakers, designating them "terrorists". It has vowed to destroy resistance groups but its offensives have killed a large number of civilians and prompted frequent international condemnation.

Current ASEAN envoy Prak Sokhonn, Cambodia's foreign minister, has complained of an absence of political will from all sides, with the lack of trust preventing anyone from coming to the negotiating table.

He said he understood criticism that his visits were one-sided and could legitimise the junta. His only notable meeting have been with the generals so far, with many cancelled. He has unsuccessfully sought the military's blessing to engage the NUG in dialogue.

HOW HAS THE JUNTA RESPONDED?

The military government has accused critical ASEAN members of meddling and warned them not to engage with the NUG. In August it cited "notable progress" on the peace plan, without providing specifics, but said its commitment would be determined by developments on the ground.

It has accused its opponents of trying to sabotage the ASEAN plan and has justified military offensives as necessary to secure the country and enable political talks.

Instead of advocating for the five-point ASEAN plan, the generals have instead been pushing a five-step roadmap of their own towards a new election, with few similarities.

WHAT APPROACHES MIGHT ASEAN TAKE?

It is unclear what proposals the foreign ministers will bring to the meeting.

Suspending Myanmar as an ASEAN member would be extremely unlikely, as would any trade sanctions, and the junta has demonstrated it will not respond to threats. Modifying the plan could be interpreted as concessions to the military.

Malaysia's foreign minister Saifuddin Abdullah has said the consensus must be seriously reviewed for its relevance "and if it should be replaced with something better".

Singapore in August said the military had disrespected ASEAN's peace effort and engaging with the junta had limited value without progress.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr last month said he would be proposing a new approach on Myanmar that "at the very least" would bring the junta or its representatives to the table.

His strategy may meet resistance, however.

ASEAN has so far opted to bar the generals from key summits and invited non-political representatives instead, which the junta has declined.