By David Lawder and Heather Timmons

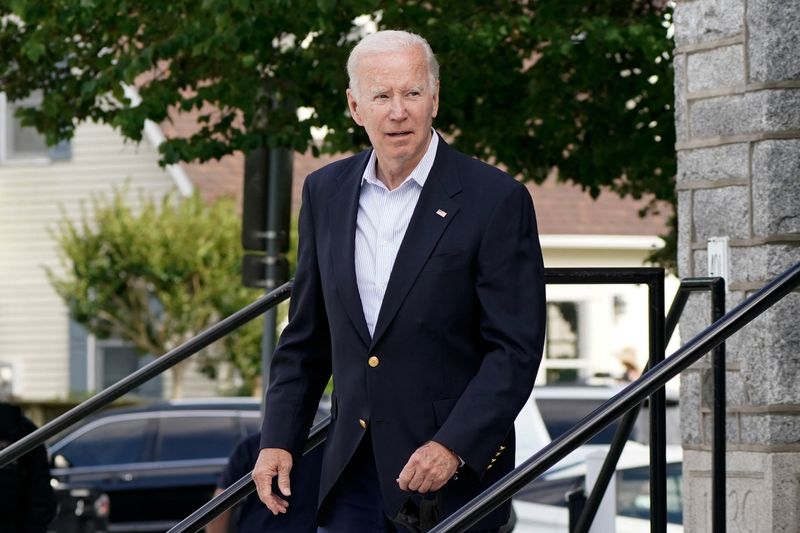

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - President Joe Biden's pointed criticism of oil and gas companies for earning massive profits as families suffer from high gasoline prices challenges a pillar of American capitalism: that U.S. companies should make as much profit as they legally can, and direct that windfall back to investors.

Biden told Shell (LON:RDSa) Plc, Exxon Mobil Corp (NYSE:XOM) and Chevron Corp (NYSE:CVX) and other refining giants last week they have another responsibility: to do everything they can to bring down high gasoline prices that are squeezing American consumers and driving up inflation.

"We see it as a patriotic duty," White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Wednesday. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has caused gas price hikes, she said.

“We know where to put the blame, on the war. But oil companies, oil refiners they have responsibilities too. What they have been doing is taking advantage of the war.”

Particularly galling to the White House is the jump in industry stock buybacks, returning to investors profits that the administration wants invested in more refining capacity to bring gasoline prices down.

Biden's criticism is being soundly rebuffed by industry executives and trade groups as having no place in an economic discussion.

"The injection of 'patriotism' into this is an attempt to put shame on folks," said Neil Bradley, chief policy officer at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the pro-business lobby group. "These are market forces and market functions."

Instead, Bradley and other industry officials say the administration should remove import tariffs and cut regulations to allow more domestic fossil fuel production and refining, which would signal to energy markets that supplies will increase.

But the idea that U.S. chief executives should serve other stakeholders besides investors, and take direction from other masters besides market forces isn't new for Biden, the U.S. presidency, or for corporate America.

His recent push is part of a slow-boil rethink of the role that companies, chief executives and the very wealthy should play in the U.S., what workers and average citizens deserve and whom governments should champion and protect.

Biden himself campaigned on a promise to fix American inequality, raise wages and force companies to pay their "fair share" in taxes, part of a broader attempt to reshape the U.S. economy.

Democrats' roughly 100-member Congressional Progressive Caucus has pushed bills expanding workers' and consumers' rights, playing a growing role in Washington lawmaking.

And these companies have made promises too. In the summer of 2019, CEOs of more than 180 big U.S. companies, including Exxon and Chevron, pledged https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans they would not only work for shareholders, but employees, customers, suppliers and their communities to "build an economy that serves all Americans."

Inflation hits poorer Americans particularly hard because they spend a greater percentage of their income on food and fuel. Asked last week about the pledge in the context of Biden's remarks, the Business Roundtable group that organized it said in an email: "BRT CEOs, including our energy members, are attempting to do just that while navigating a global energy crisis, high costs for crude oil and other inputs, and an adverse regulatory and investment environment."

Biden's attempt to shame these companies into taking less profit has historical precedent.

President John F. Kennedy attempted to curb steel prices https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-press-conferences/news-conference-30 60 years ago, criticizing "a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of private power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility," and accusing them or showing "utter contempt for the interests of 185 million Americans."

Kennedy's diatribe in April 1962 came in response to steel companies announcing a $6-a-ton price increase, shortly after agreeing to a new contract -- brokered by Kennedy's administration -- with the United Steelworkers union. A day after Kennedy's remarks, the companies rescinded the price hike.

Unlike today, the exchange came at a time when steel profits were declining, imports were increasing and shares were falling. Announcing disappointing earnings a month later, U.S. Steel Corp CEO Roger Blough reportedly told shareholders:

"This concept is incomprehensible to me – the belief that government can ever serve the national interest in peacetime by seeking to control prices in competitive American business, directly or indirectly, through force of law or otherwise.”

Jawboning companies "to reduce inflation has never been very effective," said Martin Bailly, a senior fellow in economic studies at the centrist Brookings Institution think tank.

"Biden’s frustration is understandable because there is no tool to reduce inflation except to put the whole economy into a downturn," said Bailly, an expert on regulation and productivity.

"I think the right approach is to tough this situation out. Tell Americans that the inflation is the result of disruptions from COVID-19 and the huge price shock from the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Support the Federal Reserve and say that things will be bad for some time, but we will get through this and restore growth and price stability as soon as possible."