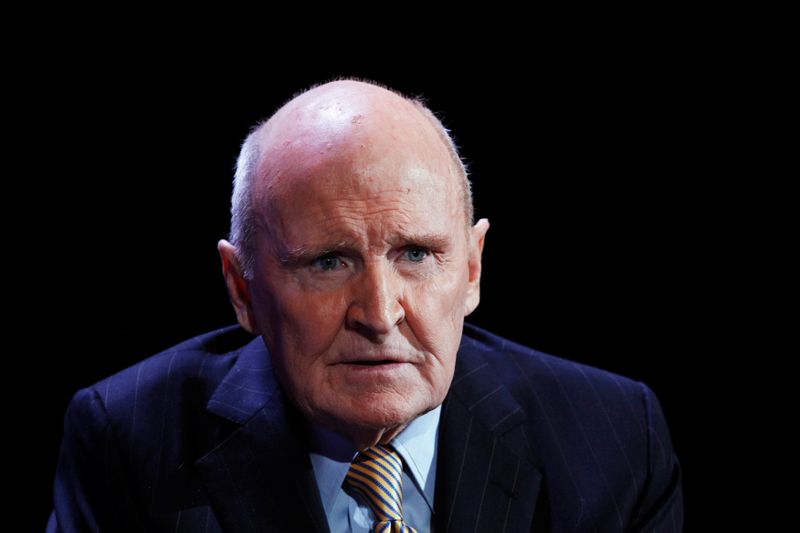

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Jack Welch, who brought celebrity and swagger to the General Electric Co (N:GE) executive suite in the 1980s and 1990s by transforming a conglomerate best-known for light bulbs into the most valuable U.S. public company, has died at 84, GE said on Monday.

Known as "Neutron Jack" for cutting thousands of jobs, Welch bought and sold scores of businesses, expanded the industrial giant into financial services and produced steadily rising profits. His success led other CEOs to begin using financial wizardry to improve earnings and wow Wall Street.

In Welch's 20 years as CEO, GE's market value grew from $12 billion to $410 billion, making Welch one of the most iconic corporate leaders of his era.

But the outsized financing business Welch built later nearly toppled GE, requiring a bailout from legendary investor Warren Buffett during the 2008 financial crisis. Welch's successor sold most of GE Capital and GE now trades at a fraction of its peak value.

"When the book about business leaders in this century is written, Jack Welch will be near the very top," said Thomas Cooke, professor at Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business. "What he did as the leader of GE was remarkable."

President Donald Trump tweeted: "There was no corporate leader like “neutron” Jack," adding his warmest sympathies "to his wonderful wife & family!"

John F. Welch, Jr., followed Reginald Jones as CEO in April 1981 and served in that role until he retired in September 2001, choosing Jeff Immelt as his successor.

Two of Welch's other top disciples - and Immelt rivals - left GE to head other major companies, helping spread Welch's management style: Jim McNerney at Boeing Co (N:BA) and Bob Nardelli at Chrysler and Home Depot Inc (N:HD).

"Today is a sad day for the entire GE family," current GE Chairman and CEO Larry Culp said in a statement. "Jack was larger than life and the heart of GE for half a century. He reshaped the face of our company and the business world."

Welch acquired new businesses and did not hesitate to use layoffs and outsourcing to streamline them, sometimes leaving shattered, embittered communities behind.

While his career at GE is mostly described as an upward trajectory, it included an early setback. In 1963, the plastics factory in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he was a chemical engineer, had an explosion that tore off the roof, and he was nearly fired. In recent years, he touted the experience as part of what created his management approach, noting that a manager at the time talked him through what he could have done better.

However, Welch was best known for his aggressive, in-your-face style and edict that GE be number one or two in every major sector - a view embraced by management consultants and business schools, said Tim Hubbard, assistant professor of management at the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business.

"It's very difficult to predict how things would have worked out if Jack stayed on deck, but certainly what happened to General Electric after he left is not a very positive story," said Hubbard. "The failure of subsequent CEOs underscores how important Welch's leadership was to GE."

A DIMINISHED CONGLOMERATE

After hitting its peak under Welch, GE's scope narrowed and its market value fell under Immelt. The company spun off much of its insurance business into Genworth Financial Inc (N:GNW) in 2004.

The transformation to industrials accelerated after the 2008 bailout. In 2015, activist investor Nelson Pelz’s Trian Partners bought a $2.5 billion stake in GE and pushed for further focus on core industrial businesses, prompting Immelt to sell of most of the remaining parts of GE Capital.

Welch often faced criticism - particularly after he retired from GE - for his cavalier attitude about offshoring jobs and shutting down U.S. plants, a theme that has grown especially potent since the election of President Donald Trump.

The U.S. industrial belt is dotted with communities devastated by the downsizing of GE, which began under Welch and has continued in the years after. At its peak, for instance, GE employed 30,000 at a sprawling integrated industrial plant in Schenectady, New York, that now employs fewer than 3,000.

Both Welch's style of management and the strategy he pursued to expand GE seem to have fallen out of favor. CEOs who order mass layoffs now get attacked in tweets from the Oval Office, and Wall Street has lost its appetite for conglomerates.

In 2012 Welch, who co-wrote a column with his wife Suzy Welch for media outlets including Reuters, sparked an outcry with a tweet suggesting the Obama White House manipulated job numbers for political gain. Click here https://www.reuters.com/article/us-jackwelch-reuters/jack-welch-terminates-column-with-reuters-fortune-idUSBRE8981CZ20121009 to read the story.

ENGINEER BY TRAINING

Born in 1935, Welch received his B.S. degree in chemical engineering from the University of Massachusetts, and his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in chemical engineering from the University of Illinois in 1960.

In 1960, Welch joined GE as a chemical engineer at its plastics division in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He was elected the company's youngest vice president in 1972 and became vice chairman in 1979.

In 1980, the year before Welch became CEO, GE recorded revenues of $26.8 billion; in 2000, the year before he left, they were nearly $130 billion. In 2001, GE was one of the largest and most valuable companies in the world, up from America's tenth-largest by market cap in 1981.

Welch also made GE a training ground for business leaders. His tough grading system provided advancement only for those who showed the best results, and weeded out the rest.

After retirement, he briefly taught a leadership course at MIT's Sloan School of Management and, later, founded an online MBA program called the Jack Welch Management Institute, now part of Strayer University.

Books by Welch include "Winning," from 2005, and "Jack: Straight from the Gut," published in 2001.

“Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others,” Welch wrote in "Winning."