By Martin Petty

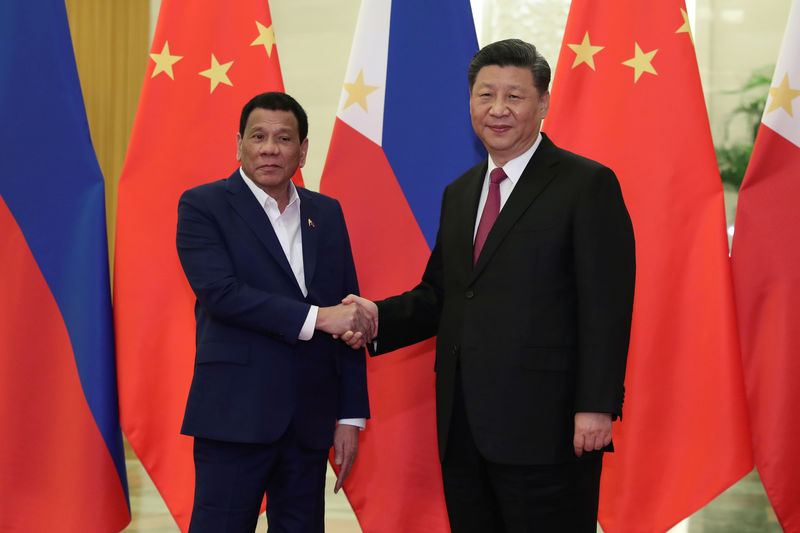

MANILA (Reuters) - When Philippine leader Rodrigo Duterte visits China this week, he'll need to salvage something from a "pivot" to Beijing that has left him empty-handed, and exposed his neighbors to a new level of brinkmanship in the South China Sea.

Despite his huge domestic popularity and great affection for China, Duterte is under growing pressure to push back at its growing maritime assertiveness. After avoiding the issue for three years, he has vowed to raise with President Xi Jinping a 2016 arbitration ruling that invalidated China's claim to sovereignty over most of the South China Sea.

The trip comes amid a recent rise in tension on multiple fronts, with Chinese vessels challenging energy assets and sea boundaries of Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines, prompting warnings and rebukes by the United States, which accuses China of "coercive interference" and holding hostage $2.5 trillion of oil and gas.

China called that "warrantless criticism" with distorted facts.

Duterte's motivation, experts say, is to tackle public unease over his refusal to speak out against a deeply mistrusted China, and frustrations among a defense establishment that has started to find its own voice.

"If that's all it is, then this is just a cynical political play. But it could be effective if it marks the start of a concerted effort to raise diplomatic costs on Beijing for its bad behavior," said Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, a Washington think-tank.

"That would mean bringing it up not just now, but at every opportunity, including introducing resolutions to the U.N. calling for Chinese compliance, and rallying international support."

"That will be a tall order ... but it's the only option that could actually work."

It would require an about-face by Duterte, who caused a storm in 2016 when he announced his "separation" from closest ally the United States, in favor of a bumper business relationship with Beijing, worth billions in loans and investment. Most of that has yet to materialize.

In return, Duterte heaped effusive praise on Xi, set aside the arbitration ruling and helped keep it off the regional agenda, creating an environment that enabled China to expand its navy, coastguard and fishing fleet and further militarize its artificial islands.

A commentary on Wednesday carried by China's Xinhua news agency said Xi and Duterte had "a firm faith and strong will to bridge their differences and push aside any distractions".

TENSION ESCALATING

After some initial calm, tensions have resurfaced this year, with Chinese coastguard tracked around an oil rig on Malaysia's continental shelf, and near an oil block in Vietnam's Exclusive Economic Zone operated by Russia's Rosneft (MM:ROSN), angering Vietnam, which is calling for international support.

Duterte's top defense officials are outraged after a Chinese trawler sank a Filipino boat in June and scores of Chinese militia boats surrounded a Philippine-held island.

Repeated unannounced movements of Chinese warships within the Philippines' 12-mile territorial waters has incensed the military, and is stoking concern about spying.

Some diplomats and analysts say building a unified position against China's militarization is still possible, despite China's strengthened hand.

Former Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario said the presence of five other Southeast Asian states and Japan as observers at The Hague arbitration showed there was significant support, and a "compelling rebuke to those who doubt that international justice does exist and will prevail".

Philippine Supreme Court Judge Antonio Carpio has been advocating that Southeast Asian countries conduct freedom of navigation and overflight activities together, and join those of the United States, Japan, India and Britain.

But finding a common approach would be difficult, according to Jay Batongbacal, a South China Sea expert. He said Duterte had weakened the international position by allowing China to consolidate power "without interference or even a peep from us".

Much depended on China's actions, and whether Western powers were convinced that Duterte and other Southeast Asian leaders were prepared to confront Beijing.

"If China pushes, it may raise the possibility of us unifying around that ruling," he told news channel ANC.

"If we don't speak up, they will not be able to take a stronger position."