By Jeffrey Dastin and Julia Love

(Reuters) - Earlier this year, Amazon.com Inc (NASDAQ:AMZN) handily defeated a historic union drive at a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama. But with the prospect of another vote looming, the online retailer is leaving nothing to chance.

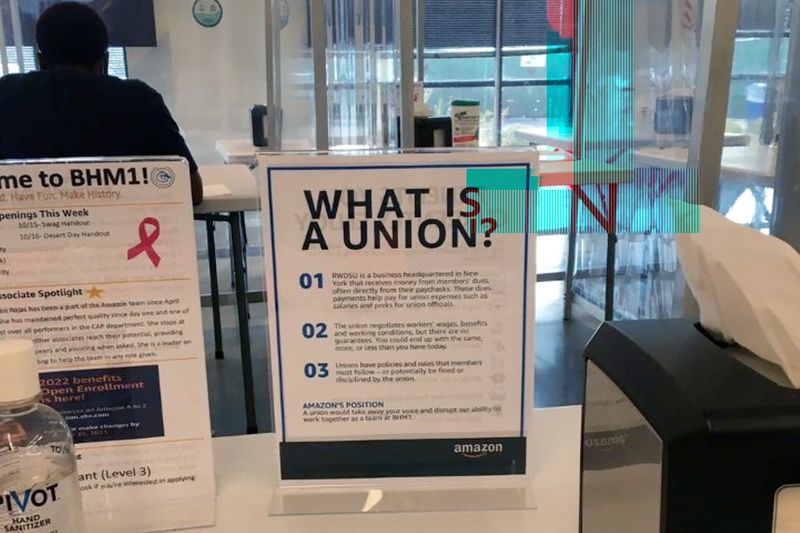

Over the past few weeks, Amazon has ramped up its campaign at the warehouse, forcing thousands of employees to attend meetings, posting signs critical of labor groups in bathrooms, and flying in staff from the West Coast, according to interviews and documents seen by Reuters.

It is an indication that Amazon is sticking to its aggressive playbook. In August, a U.S. National Labor Relations Board hearing officer said the company's conduct around the previous vote interfered with the Bessemer union election. An NLRB regional director's decision on whether to order a new vote is forthcoming. Amazon has denied wrongdoing and said it wanted employees' voices to be heard.

Still, the moves to discourage unionization ahead of any second election, previously unreported, show how Amazon is fighting representation at its U.S. worksites.

An uptick in labor activity since workers in April rejected joining the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU), including organizing drives in New York and Canada, has pushed Amazon to react.

Other prominent unions like the International Brotherhood of Teamsters are also vowing to organize Amazon. The risk: unions could alter how Amazon manages its vast, finely tuned operation and drive up costs at a time when a labor shortage is taking a toll on its profit.

Wilma Liebman, a former NLRB chair, said the stakes are high.

"They really, really fear any toe in the door to unionization," Liebman said. "There's nothing like a win, and a win can be contagious."

In a statement, Amazon spokesperson Kelly Nantel said a union "will impact everyone at the site so it's important all employees understand what that means for them and their day-to-day life working at Amazon."

In the new campaign, Amazon has dedicated a week of mandatory meetings to warn staff that unions will force them to strike and forgo pay, a nod to the recent stoppages roiling workplaces across the country.

And like last time, Amazon has said unions are a business taking workers' money and told staff to consider what it can guarantee and what unions cannot - now in panels in bathroom stalls and above urinals. The panels carry information unrelated to unions as well.

"Unions can make a lot of promises, but cannot guarantee you will receive better wages, benefits, or working conditions," read a photo shared with Reuters.

UNION SUPPORTERS PUSH BACK

Some staff have challenged Amazon's claims and posted their own pro-union signs in warehouse bathrooms, according to worker accounts.

The RWDSU, meanwhile, has flown in personnel to Bessemer, facilitated nightly chats at a burger joint, and ramped up door-knocking. Home visits are a crucial part of organizing drives because unions have no guaranteed worksite access under U.S. law, said John Logan, a professor at San Francisco State University.

Stuart Appelbaum, the RWDSU's president, said the union has heard from employees who now would change their vote to join. He said he believes door-knocking gives the union a new edge.

"We have a greater opportunity to engage with people every day than during the height of the pandemic," said Appelbaum. Organizers did not conduct home visits last time because of COVID-19 fears.

He added that the RWDSU's effort is about more than Amazon. "It's about the future of work."

A Teamsters spokeswoman said the union has attended strategy meetings on Amazon with other unions coordinated by the biggest U.S. labor federation, the AFL-CIO. Tim Schlittner of the AFL-CIO said the federation is "bringing the resources of the labor movement" to support Amazon workers.

Roadblocks abound, not least that the RWDSU has to reach new staff joining the company without knowing their names until an official election is ordered. Appelbaum estimated that Amazon was hiring 200 people a week in Bessemer.

Amazon had no comment on turnover. The warehouse headcount numbers more than 5,800.

SCARE TACTIC

On Oct. 10, just when Amazon raised hourly wages by 25 cents for more veteran staff, the company re-started mandatory weekly meetings in Bessemer to highlight different messages about unions. Amazon said the pay increase was unrelated to the meetings.

For Darryl Richardson, an outspoken union supporter at the facility, strikes were a bigger focus of Amazon's new campaign.

"They're trying to scare you more now," Richardson said. "You don't get paid going on a strike."

According to Richardson, Amazon falsely said a union would force workers to walk off the job and fine them if they crossed a picket line. The 52-year-old said Amazon has treated him differently as well: he was denied transfer requests, and an official walking through the warehouse to ask workers how they felt about unions had little to say after scanning Richardson's badge ... "'You're Darryl,' she said. 'Your mind is made up.'"

Amazon had no comment on Richardson's remarks.

Though the company told employees they can turn away organizers showing up at their doorsteps, Richardson said he and peers have kept knocking, while Amazon is making its case on home turf.

In one table-top sign Amazon put up at the warehouse, the company exhorted workers to "FOLLOW THE MONEY," claiming the RWDSU gave Appelbaum a "$30,000 raise paid for by union dues" and last year spent nearly $100,000 on cars for its officials.

Asked for comment, Appelbaum said he has no union car and that transportation is for field representatives whose jobs require travel to workplaces.

Amazon is "misrepresenting the information," he said.