By Elizabeth Culliford

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - When Brian Durst got a text message from the campaign of U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, the restaurant cook in Hawaii sent back a photo of himself wearing a 'Trump 2020' cap.

Three minutes later, he got a reply from someone named Will from the Vermont senator's campaign asking if he had a second choice candidate. Durst shot back an angry message listing Vice President Mike Pence and members of Republican President Trump's family, and tweeted out a screenshot of the exchange.

As the 2020 presidential campaigns push out tens of millions of text messages to find potential supporters, some Americans are texting back to vent frustrations, argue about candidates' stances or try to convert the volunteers.

(Get all the Super Tuesday action: https://www.reuters.com/live-events/super-tuesday-id2923975)

But it turns out even uncooperative replies can be helpful data.

Campaign texters log numerous details from responses, no matter what the content. They can use them to verify names and working mobile numbers, score how voters feel about the candidate and register their first and second choices as well as the issues the voter cares most about.

"That's where the gold is," said Thomas Peters, the founder and CEO of RumbleUp, a peer-to-peer texting company used by the Republican National Congressional Committee, which also allows campaigns to measure positive or negative sentiment in replies.

The script for Elizabeth Warren's texters tells them to record details such as whether voters are concerned with the Massachusetts senator's electability and if they have "hot button issues" like college affordability.

A training webinar for Sanders' volunteers showed options to mark for reasons someone would not attend a rally, from whether they had moved to if they fit the category "Refused/Angry/Republican.'

Political campaigns see peer-to-peer texting as an effective way to identify supporters, drum up volunteers and get out the vote: in the 2018 cycle, Democratic campaigns and political groups sent at least 350 million text messages, according to a report by progressive non-profit Tech for Campaigns.

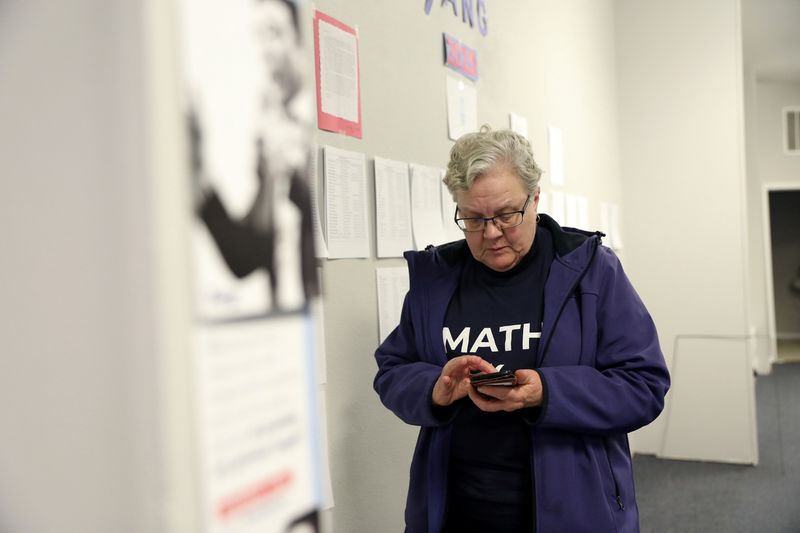

These messages need to be sent by a human to not fall afoul of anti-spam laws which prohibit sending mass texts without an opt-in from recipients. Campaign volunteers and staffers use software to manually send out prewritten messages, which can be customized, to lists of phone numbers.

Campaigns gather these phone numbers and other data from their supporters, who might have responded to events and surveys, and from voter registration lists which can have other information appended to them. Durst, for instance, said he had previously been registered as a Democrat. The parties can update their voter files with data gathered from texting campaigns.

In January, Trump's campaign director Brad Parscale tweeted a screenshot of a text he received from the Sanders campaign: "Haha," he texted back. "Your data is really really bad if you are texting me."

Daniel Souweine, who founded the left-leaning political texting company GetThru after he ran Sanders' texting program in 2016, thinks campaigns will be increasingly sophisticated about how they use the information collected in text conversations.

"They have literally every message that has been sent," he said.

Some voters try to throw a wrench in the works, however: The popular Twitter pundit @RespectableLaw recently listed ways that voters could waste the time of texters for former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg in particular by pretending to be undecided or asking a string of policy questions.

The billionaire's campaign, which pays its digital organizers to send texts to their own social media networks, also uses peer-to-peer texting.

"Never let them know who you really support. This is a data mining operation. Sabotage it wherever possible," said one of the tweets in @RespectableLaw's thread, which got 9,000 likes.