By Howard Schneider

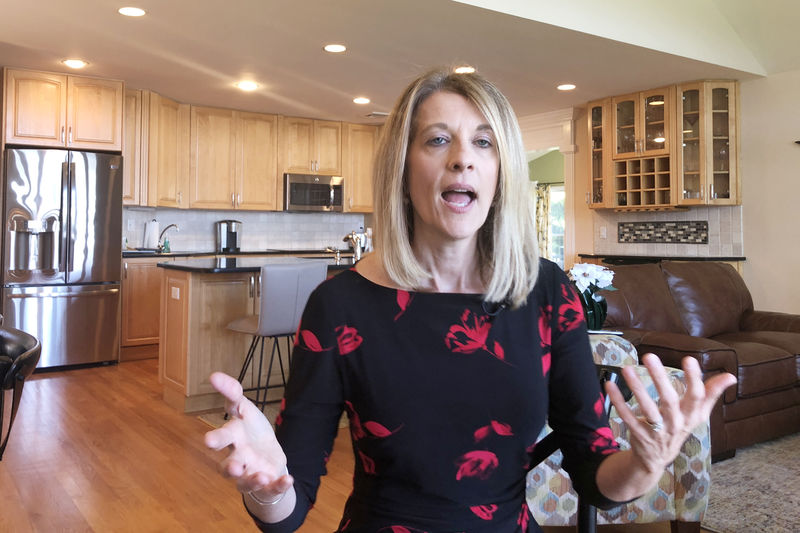

SETAUKET, New York (Reuters) - From her home overlooking Setauket Harbor on Long Island's North Shore, a motorboat bobbing at the dock, Stephanie Kelton hopes to revolutionize how the U.S. government manages the economy.

It isn't always a pleasant task.

A key figure in the "Modern Monetary Theory" economic camp, her assertions that the federal government could spend freely for things like a jobs guarantee or Green New Deal without risking runaway inflation, a debt default or a clubbing by global creditors have been Twitter-bombed by mainstream economists as left-wing free lunchism.

Proponents of MMT have been called fanciful for the notion that the U.S. Congress, which typically struggles to pass an annual budget, could with smart budgeting and regulation take over the Federal Reserve's job of controlling inflation.

And even Kelton, an economics professor at Stony Brook University in New York and an adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders' presidential campaign, is a bit thrown by the fact that the person who appears closest to accepting her argument is President Donald Trump, whose Republican Party has traditionally touted an adherence to fiscal discipline.

Trump and Republicans in Congress, she said, "did not allow perceived budget constraints to stand in their way" of a $1.5 trillion tax cut package which was passed in late 2017 and pushed the federal debt beyond $22 trillion.

Democrats now seem ready to get in the game.

Lawmakers from both parties recently reached a federal spending deal that is expected to raise the federal deficit by $2 trillion over the next two years, and Democrats lining up to run against Trump in 2020 have largely avoided talk of fiscal restraint so far in the campaign.

Groups like the Center for Equitable Growth have begun developing ideas for new "automatic stabilizers" that would boost federal spending in a downturn without action by Congress, something Kelton argues could be achieved with a jobs guarantee to absorb those thrown out of work when the economy weakens.

'VOODOO ECONOMICS'

Some of Kelton's highest-profile critics, like former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, agree the United States should worry less about debt, more about public investment, and accept that fiscal policy - deficit spending - needs a greater role in future U.S. economic policy.

They part ways, though, over the Kelton camp's contention that the risks of excessive government debt are far overstated by mainstream economists largely because the U.S. government borrows in its own currency, and any threat of excessive inflation can be countered by regulation or even tax hikes that would rein in spending.

While Summers, who had key roles in the Obama and Clinton administrations, has decried such assertions as "voodoo economics," other notable economic figures including Ray Dalio, the founder of hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, say policies like those Kelton embraces have become "inevitable" in the "new normal" economy.

With interest rates stuck at historically low levels and inflation weak, central bankers themselves wonder if they have the tools to weather the next downturn, and what can lift the economy if they don't.

To Kelton and other MMT adherents, that is emblematic of a system that needs changing in favor of one where Congress simply spends what is needed to ensure full employment and adequate demand, the Treasury writes the checks, and the Fed prints the money to cover them.

It isn't, she said, a recipe for "infinite" spending, as her critics suggest. Inflation is the constraint that would prevent it. But she argues that Congress, not the Fed, could manage the pace of price increases while still meeting the goal of full employment, and that the public could discipline elected officials at the ballot box if it was not done well.

Those are large leaps of faith. But Kelton, who helped develop MMT in the 1990s, argues they are warranted in an era when inflation is not a problem, unemployment remains high among some minority groups and in some regions, and a sort of war-like initiative is needed to direct the investment needed to combat climate change.

"Look at what the world looks like not just in the U.S., but much of Europe and Japan," she said. "We operate chronically with governments that don't run their budgets aggressively enough, and as a result you have unemployment and stagnation."

But even Democratic presidential candidates with ambitious spending plans, including Sanders, a democratic socialist, have not publicly endorsed MMT. The theory also is not headlined on campaign websites dense with spending plans.

Yet, it has worked its way into the national debate, partly out of an acknowledgement that monetary policy may not be able to ride to the rescue in another deep downturn.

Even officials at the U.S. central bank wonder if their existing framework is wobbly, and whether they need a better sense of how to define full employment in an economy with wide disparities among regions and demographic groups.

That only proves the current arrangement isn't working, Kelton said, in the United States or Europe. Japan is struggling as well, though notably there is now a constituency inside the Bank of Japan arguing for something like MMT - a major fiscal push to try to jolt the country away from its dangerously low levels of inflation.

MMT supporters may not be alone in seeing a greater fiscal role as necessary. They just don't see the need to wait for a crisis to make a move.

"People are thinking ahead. We are not going to be leaning on central banks exclusively ... That is encouraging," Kelton said. Congress "already has all the powers they need ... We cannot ask the power of the purse to make us all rich and wealthy and never have to work. But we can do better."