By Lawrence Hurley

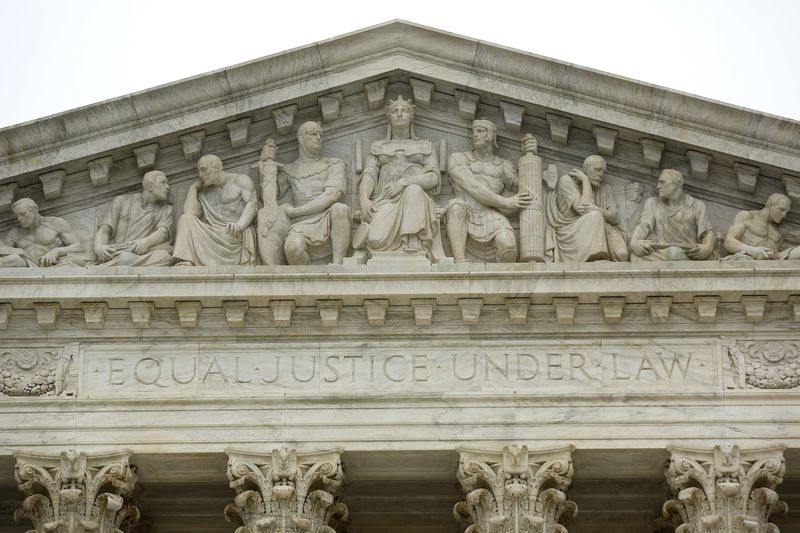

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday appeared torn as it weighed a major civil rights case that could narrow the scope of discrimination claims made under the landmark Fair Housing Act.

Based on the one-hour oral argument, it is not clear if there is a conservative majority on the nine-justice court that will cut back on what kind of conduct can lead to housing discrimination litigation.

Most significantly, the reliably conservative Justice Antonin Scalia made some remarks supportive of the argument made by President Barack Obama's administration and civil rights groups in defense of the broad interpretation of the law.

The court is considering whether the 1968 law allows racial and other bias claims based on seemingly neutral practices that may have a discriminatory effect. These are known as "disparate impact" claims. There is no dispute over the law's prohibition on openly discriminatory acts in the sale and rental of housing.

The case concerns whether Texas violated the Fair Housing Act by disproportionately awarding low-income housing tax credits to developers who own properties in poor, minority-dominated neighborhoods.

Two court conservatives, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, seemed inclined to narrow the law's scope.

But Scalia said that although the 1968 law did not specifically refer to disparate impact claims, Congress appeared to acknowledge the existence of such claims when it amended the law in 1988.

"Why doesn't that kill your case?" Scalia asked Scott Keller, the lawyer for Texas arguing the claims should not be allowed.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who often casts the deciding vote in close cases, said little during the argument.

In one exchange with U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, who argued for a broad interpretation of the law, Kennedy seemed to support Texas' argument. He said it "seems very odd to me" that a local government agency could be liable for development decisions in a wide range of contexts.

The court's liberal justices defended the existing interpretation of the law, which has been backed by lower courts but never endorsed by the high court.

Justice Stephen Breyer told Keller that decades of law are "universally against you."

The case is closely watched by lenders and insurance companies.

Civil rights groups had sought to keep the issue away from the conservative-leaning high court. In the past three years, two other cases that raised the same issue were taken up by the high court but settled before the justices could issue a ruling.

A decision is due by the end of June.

The case is Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, U.S. Supreme Court, No. 13-1371.