By Jarrett Renshaw and Richard Valdmanis

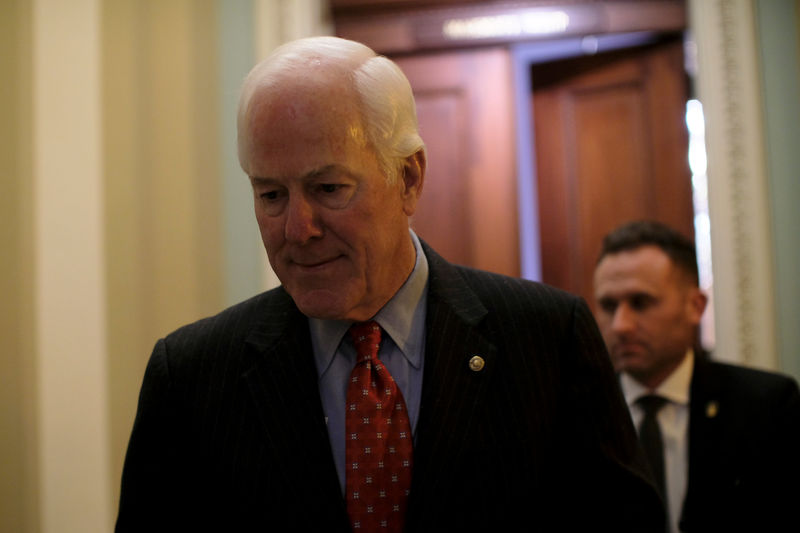

(Reuters) - Senator John Cornyn, the No. 2 Senate Republican, is trying to win support from the Midwest corn lobby for a broad legislative overhaul of the nation's biofuels policy, according to sources familiar with the matter.

The effort comes as President Donald Trump's White House mediates talks between the rival oil and corn industries over the Renewable Fuel Standard, which requires oil refiners to blend increasing amounts of corn-based ethanol and other biofuels in the nation's fuel supply every year.

Oil refiners say the regulation costs them hundreds of millions of dollars a year and is threatening to put a handful of the nation's refineries out of business. Ethanol interests have so far refused to budge on proposals to change it.

Cornyn "is working hard to unify all stakeholders in a consensus effort to reform the Renewable Fuel Standard," an aide to the senator told Reuters. The aide, who asked not to be named, did not provide details.

Cornyn, of Texas, the U.S. state that is home to the most oil refineries, is part of the Senate's leadership team, responsible for securing the votes needed to pass the Republican party's legislative agenda.

Two lobbyists for the oil refining industry said Cornyn was having some success cobbling together a coalition of lawmakers and stakeholders around a potential RFS reform bill that could be dropped early next year. However, similar efforts to unify these rival factions have fallen flat in the past.

Any such effort would need the buy-in of legislative backers of the ethanol industry, like Republican Senators Chuck Grassley and Joni Ernst of Iowa, the top-producing state for corn. Officials for the senators did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Both Grassley and Ernst have previously repeatedly expressed their intention to defend the RFS in its current form.

The White House has been hosting negotiations between both sides of the issue over short-term remedies that can provide relief to refiners struggling with the existing regulation. The refining industry says compliance now costs it hundreds of millions of dollars a year, and threatens to put some refineries out of business.

Refineries that do not have adequate facilities to blend ethanol into their gasoline must purchase blending credits, called RINS, from rivals that do. RIN prices have risen in recent years as the amount of biofuels required under the RFS has increased.

Refineries that buy RINs include Philadelphia Energy Solutions and Monroe Energy, both of Pennsylvania, and Valero Energy Corp (NYSE:VLO) of Texas.

Valero said RINs cost it around $750 million last year, though there are competing arguments over whether refiners pass along those costs.

Senator Ted Cruz, also of Texas, last week sent a proposal to the White House to cap the price of RINs at 10 cents each, a fraction of the current price. The proposal was widely rejected by the ethanol industry.

The ethanol industry has said in the past that placing caps on the credits was a non-starter, and has instead argued for policies to increase volumes of ethanol in the U.S gasoline supply. The industry claims this would boost supplies of the credits, lowering their prices.

Prices of renewable fuel credits have fallen in recent weeks on reports of the discussions in Washington. The price hit 68 cents on Wednesday, nearing a seven-month low, according to traders and Oil Price Information Services.

The White House has not yet commented on Cruz's proposal.

The RFS was introduced by former President George W. Bush as a way to boost U.S. agriculture, slash energy imports and cut emissions. It has since fostered a market for ethanol amounting to 15 billion gallons a year.

The refining industry has pressed the Trump administration repeatedly to adopt reforms that would lower the credit costs or otherwise ease the burden on refineries, but the ethanol industry has successfully defeated those efforts so far.