By Joseph Ax

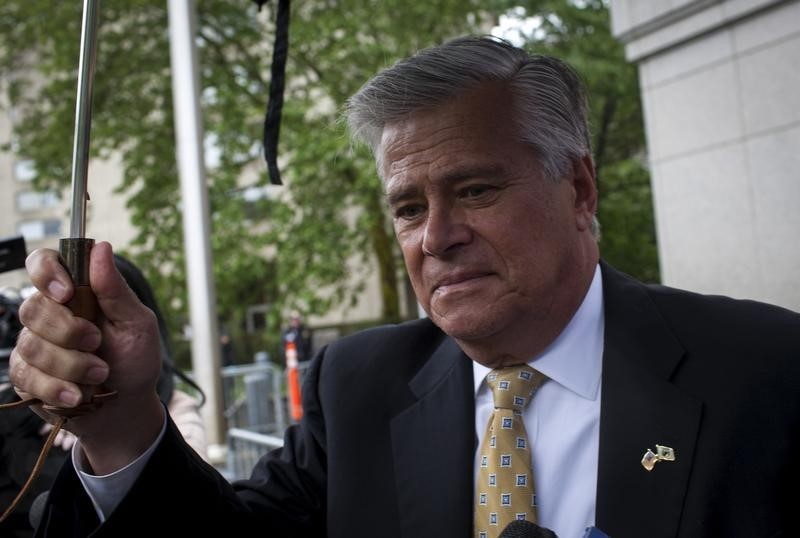

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Former New York state Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos used his official position to cajole companies into giving his son Adam consulting payments, a "no-show" job and a check all worth about $300,000 in exchange for his political favor, prosecutors said on Tuesday as they wrapped up the case against them.

"Beginning in 2010, these two men began a multiyear scheme to corrupt one of the most powerful offices in our state," Assistant U.S. Attorney Rahul Mukhi said as the three-week trial in New York neared an end. "They did it by turning Senator Skelos' office into a cash cow."

The defense, which has denied the existence of any quid pro quo arrangement, is expected to deliver closing arguments on Wednesday.

Skelos is the second powerful legislative leader to stand trial this year. Former State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver was convicted last week in the same Manhattan federal court of collecting millions of dollars in bribes and kickbacks.

Together, the Silver and Skelos prosecutions represent the high point thus far in a broad campaign by Preet Bharara, the U.S. Attorney in Manhattan, to root out corruption in the state capital, Albany.

Silver and Skelos were two-thirds of the so-called "three men in a room," along with the governor, who wield virtually absolute control over major legislation.

The closing arguments in the Skelos trial came after both Dean and Adam Skelos elected not to testify or call any witnesses in their defense. They have been charged with eight counts of bribery, extortion and conspiracy.

Skelos, 67, a Republican, is accused of strong-arming three companies to pay Adam Skelos more than $300,000, knowing they could not refuse.

"If you got on the wrong side of the majority leader, he could gut your entire business under the cover of night," Mukhi said.

Within days of becoming majority leader in 2010, Skelos initiated what would become a "blizzard" of requests that the companies pay his son, Mukhi said. In exchange, prosecutors said, Skelos supported legislation in Albany that aided their businesses.

Representatives of the companies testified at trial that they agreed to pay Adam Skelos, even though he did little or no work, because they feared angering his father.

Defense lawyers for both men have argued that prosecutors have overreached.

"The government is trying to turn a very normal father-son relationship into a crime just because of who his father is," Christopher Conniff, Adam Skelos' lawyer, said in his opening statement last month.