By Joseph Ax

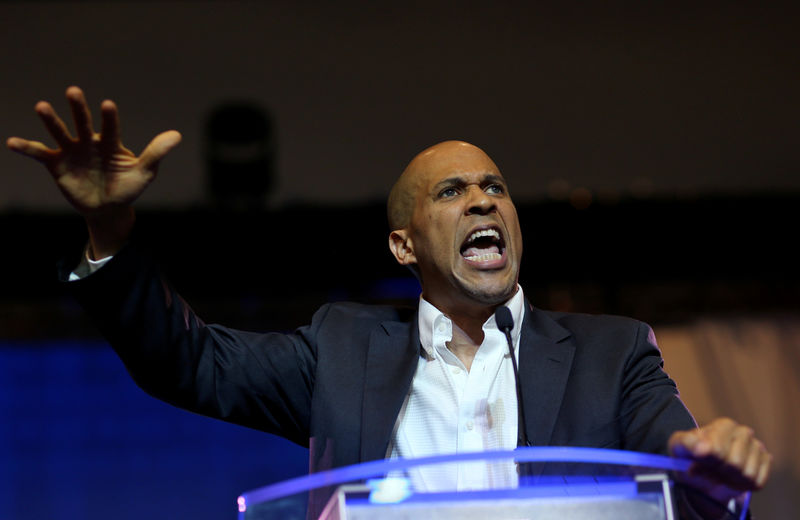

NEWARK, N.J. (Reuters) - U.S. Senator Cory Booker's best hope of capturing the Democratic presidential nomination may be reassembling the coalition that propelled Barack Obama to the White House in 2008, consolidating the black vote while inspiring young Democrats to back him.

Obama largely eschewed explicit mentions of race, wary of provoking a backlash to his historic candidacy. But Booker, who would be the first U.S. president descended from slaves, has frequently brought the subject to the fore.

That strategy was on display at the first Democratic debate on Wednesday. Forty seconds into his first answer - in response to a question about breaking up technology companies - the former Newark, New Jersey, mayor said, "I live in a low-income black and brown community. I see every single day that this economy is not working for average Americans."

Throughout the evening, Booker drew connections between policy matters and race, whether it was the impact of inadequate health care on African-Americans, persistent racial bias in the criminal justice system or recent attacks on transgender people, which he compared to the lynching of blacks in the South before the civil rights movement.

When asked about gun safety, he spoke about inner-city violence, saying he was the only candidate who had seven people shot in his neighborhood last week.

Booker, 50, is betting voters will embrace a more candid conversation on race, a decade after Obama became the first black president and during a Trump administration accused by many Democrats as being racially divisive.

His message is aimed not only at black voters, a crucial Democratic constituency whose turnout dropped after Obama's elections in 2008 and 2012, but also at left-wing voters driving the party's anti-Donald Trump enthusiasm.

"Race is now not a taboo to talk about on the campaign trail. It is one of the primary ways to signal how progressive you are," said Theodore Johnson, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice who studies the intersection of race and politics.

Booker has been polling at around 2% support, seventh among more than 20 Democrats running.

He draws higher support from black voters but faces stiff competition from U.S. Senator Kamala Harris, the other leading African-American candidate, and former Vice President Joe Biden, who enjoys deep loyalty among black voters after eight years as Obama's right-hand man.

The debate followed a week in which Booker called on Biden to apologize for expressing nostalgia about working civilly with segregationist senators; unveiled an ambitious clemency proposal to address racially biased prison sentences; and slammed Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell for dismissing the notion of reparations for descendants of slaves.

"Fifteen years ago, you'd never have talk about reparations in the presidential campaign," said Jaime Harrison, the first African-American chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party and a 2020 U.S. Senate candidate.

Both Harris and Booker have made the early voting state of South Carolina, where black voters hold a majority among Democrats, a top priority.

On the trail, Booker describes his family's journey through the country's fraught racial history, including his parents' fight to integrate the white New Jersey suburb where he grew up.

His signature "baby bonds" proposal to give every American a government-backed savings account at birth takes aim at the wealth gap between white and black families.

He speaks often about U.S. racial inequities in criminal justice, voting rights and housing policy, warning Americans must not engage in "historical amnesia" about generations of racist policies.

"The tradition has been that you don't blaze into office talking about racial disparities," Johnson said. "The colorblind approach has been how successful black politicians have often run."

That was largely the approach taken by Obama, who engaged with racial issues only when forced upon him.

'HAPPY MEDIUM'

In recent years, however, the Black Lives Matter movement gave voice to deep frustration among African-Americans over police mistreatment, while Trump's handling of the racial violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, during a white supremacist rally prompted widespread outrage.

U.S. Representative James Clyburn, a prominent black leader from South Carolina, said Booker and other politicians addressing race directly was not necessarily a choice of their own making.

"I think the times have dictated that the choice must be made," he said.

Booker couches his calls for action in broader terms, arguing the civil rights movement succeeded by working across color lines.

When he recounts his parents' efforts to buy a home in Harrington Park, New Jersey, one of the heroes is a white lawyer who volunteered to help black families combat housing discrimination.

"He's trying to strike the happy medium, where he can talk candidly about race and be forceful about it, but also talk about it in a way that won't alienate" white voters, said Andra Gillespie, a professor at Emory College and author of "Symbols, Substance and Hope: Race and the Obama Administration."

Like Harris, whose career as a prosecutor has drawn skepticism from some black activists, Booker has occasionally faced scrutiny from other African-Americans.

After graduating from Yale Law School in 1997, he moved into a public housing complex in Newark. During his first losing mayoral campaign, the black incumbent openly wondered whether Booker was "black enough."

But Booker's supporters say his lived experience - growing up in an affluent white suburb before moving to a crime-ridden inner city - will resonate with black voters.

"At the end of the day, because he has had to navigate that," said Steve Phillips, an African-American businessman who launched a super PAC to support Booker's candidacy, "he is very comfortable in his own skin."