By Howard Schneider and Steve Holland

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - There were no fancy economic models or forecasts when former Florida Governor Jeb Bush first tossed out the idea that 4 percent annual growth should be the overarching goal for the U.S. economy.

But what started as a casual suggestion during a 2010 conference call with advisers to the George W. Bush Institute, a public policy center in Dallas, has now become the central economic idea of Bush's developing run for the White House. Details of the call were recounted by one of the participants to Reuters.

The goal is ambitious: 4 percent growth is well beyond the U.S. average since World War Two and nearly double what many economists regard as the country's current potential. Nevertheless, the idea has become the frame for a series of Bush proposals, ranging from bread-and-butter tax reform to a wholesale rewrite of immigration law.

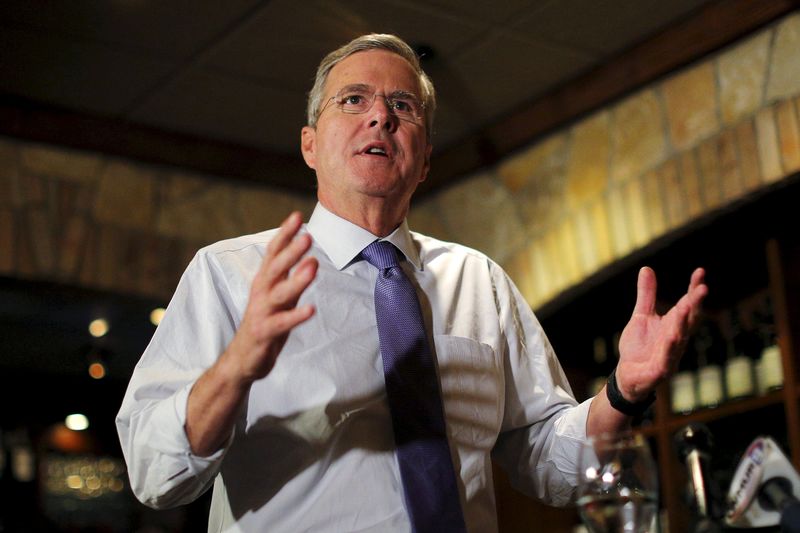

Asked by Reuters during a campaign-style stop in New Hampshire on Thursday how he had arrived at the figure, Bush said: "It's a nice round number. It's double the growth that we are growing at. It's not just an aspiration. It's doable."

Bush faces a crowded field of Republican presidential hopefuls whose economic ideas range from Kentucky Senator Rand Paul's crack-down-on-the-Fed monetary policies to Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker's tough line against unions. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie echoes Bush's 4 percent goal.

If, as widely expected, Bush runs for the White House he will have to position himself as the best candidate, Republican or Democrat, to restore lagging wage growth for middle- and lower-income families.

"Fixing how we tax and how we regulate, and embracing an economically driven immigration system rather than a family-oriented immigration system," are key steps towards achieving that economic growth goal, Bush said on Thursday. "Dealing with the fiscal challenges of Washington that create uncertainty and embracing the energy revolution," would also help the economy achieve 4 percent growth.

"A rising young aspirational population combined with continued productivity could get you to 4 percent," he said.

CONFERENCE CALL

That ambitious goal was first raised as Bush and other advisers to the George W. Bush Institute discussed a distinctive economic program the organization could promote, recalled James Glassman, then the institute's executive director.

"Even if we don't make 4 percent it would be nice to grow at 3 or 3.5," said Glassman, now a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. In that conference call, "we were looking for a niche and Jeb in that very laconic way said, 'four percent growth.' It was obvious to everybody that this was a very good idea."

The goal, embraced by the institute, quickly took on a life of its own. By April 2011 there was a conference in Dallas and subsequent book of essays, "The 4% Solution," in which Nobel economists like Robert Lucas and Edward Prescott dissected what it might take.

They mapped out the pitfalls of high taxes and how that seemed to discourage work in Europe, while others like economist Peter Klein criticized the U.S. Federal Reserve's easy money policies for creating an uncertain world for entrepreneurs.

Still, Prescott acknowledged, while 4 percent growth was "reasonable, even modest" for an economy recovering from a deep recession, 3 percent was the country's "maintainable" rate of growth.

MAKING THE PIE BIGGER

Bush's focus on 4 percent is an attempt to "focus away from more divisive issues to something everyone can agree with ... Don't argue over dividing the pie, make the pie bigger," said Barry Bosworth, an economist and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

The problem, Bosworth said, is that the goal is "disconnected to reality," with productivity lagging and the rush of baby boomers to the pension rolls leaving comparatively fewer workers behind to expand the economy.

Four percent growth is not unheard of in the United States. It has happened in 27 of the years since 1947. The last such period of growth was during the Clinton administration in the 1990s when there was controlled inflation, high productivity and strong investment surrounding the expansion of the Internet.(Graphic: http://link.reuters.com/quv74w)

But it is not the norm. The average since World War Two has been just over 3 percent. Current models of the U.S. economy used at the Fed, for example, see long-term trend growth even lower, at just over 2 percent as pension rolls swell, productivity lags, and U.S. businesses and workers compete in a more fully globalized world.

Stanford University economist John Taylor, known for his contributions to monetary policy and central banking theory and considered a possible high-level appointee in a Republican administration, said 4 percent growth was possible if one melded the best of the Reagan and Clinton years – a combination of deregulation, tax and entitlement reform, and shrinking federal deficits.

In both of those administrations, the economy was at or above 4 percent at least half the time, and "that is evidence that things could be like that again," Taylor said in an interview.