By Sharon Bernstein

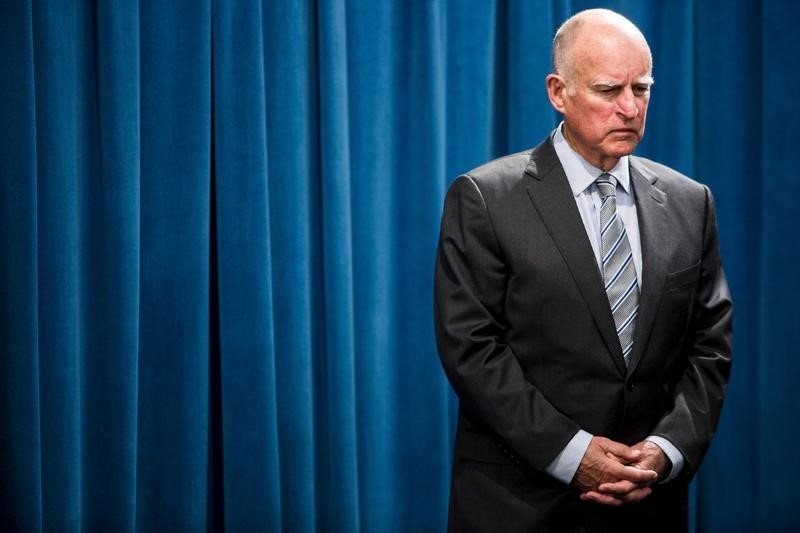

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (Reuters) - Physician-assisted suicide will become legal in California under a bill signed into law on Monday by Democratic Governor Jerry Brown, despite intense opposition from some religious and disability rights groups.

The law, based on a similar measure in Oregon, allows doctors to prescribe medication to end a patient's life if two doctors agree the person has only six months to live and is mentally competent.

In a rare statement accompanying the signing notice, Brown, a former Roman Catholic seminarian, said he closely considered arguments on both sides of the controversial measure, which makes California only the fifth U.S. state to legalize assisted suicide for terminally ill patients.

"I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain," Brown said. "I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn't deny that right to others."

The law, which goes into effect Jan. 1., makes it a felony to pressure anyone into requesting or taking assisted suicide drugs.

Advocates for physician-assisted suicide have tried for decades to persuade California to legalize the practice as a way to help end-stage cancer and other patients to die with less pain and suffering, failing six times in the legislature or the ballot box before finally winning passage last month.

The latest bill was introduced amid nationwide publicity over the case of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old brain cancer patient who moved from California to Oregon to take advantage of that state's assisted suicide law and died there.

"My wife, Brittany Maynard, spoke up last year to make a difference for terminally ill individuals who are facing a potentially harsh dying process," said Maynard's widower, Dan Diaz, who lobbied passionately for the bill when it was before the legislature.

The California bill was strongly opposed by some religious groups, including the Roman Catholic Church, as well as advocates for people with disabilities, who said unscrupulous caregivers or relatives could pressure vulnerable patients to take their own lives.

LAW'S PROTECTIONS QUESTIONED

Opponents also said the bill would invite insurance companies to take advantage of poor patients by offering to pay for the cost of life-ending drugs but not for the expensive treatments that could save lives.

"There is a deadly mix when you combine our broken healthcare system with assisted suicide, which immediately becomes the cheapest treatment," said Marilyn Golden, a senior policy analyst at the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund in Berkeley. "The so-called protections written into the bill really amount to very little."

But supporters said the measure would allow people who are terminally ill to die with dignity and greater comfort.

"My daughter did not die in vain," said Dr. Robert Olvera, an advocate for the measure whose daughter succumbed to leukemia in 2014. "This is the option she wanted to end her suffering."

As presently written, the law will expire after 10 years unless extended, a compromise with lawmakers who were worried about unintended consequences such as the targeting of the poor, elderly and disabled.

Physician-assisted suicide is already legal in the states of Oregon, Washington, Montana and Vermont.

On Monday, the advocacy group Compassion and Choices, which backed and lobbied for the measure, called on other states to follow California's lead.

Opponents were quick to react, saying that passage in other states was far from inevitable.

Tim Rosales, a spokesman for Californians Against Assisted Suicide, said his coalition had not yet decided whether it would sue to stop the new law from going into effect.

But he downplayed the likelihood that advocates would be able to quickly mount campaigns in other states, saying it would be difficult for them to raise enough money to go state by state and fight for such a controversial proposal.