By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The tusks of a stoutly built plant-eating mammal relative that inhabited Antarctica 250 million years ago are providing the oldest-known evidence that animals resorted to hibernation-like states to get through lean times such as polar winters.

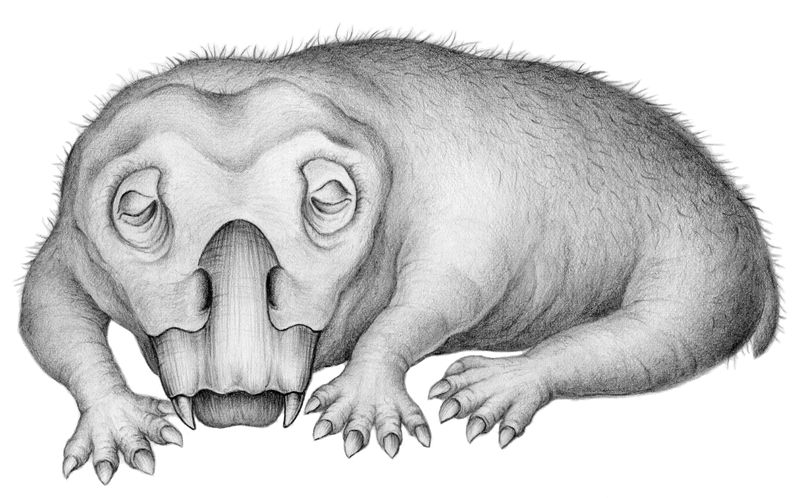

The research published on Thursday focused on a four-legged forager called Lystrosaurus whose fossils have been found in China, Russia, India, South Africa and Antarctica. It was an early member of the evolutionary lineage that later gave rise to mammals.

The findings indicated that Lystrosaurus entered a state of torpor - a temporary reduction in metabolic activity - to cope with the long, perpetually dark winters in the Antarctic Circle when food was scarce, although Earth then was much warmer than today and the region was not ice-bound.

The findings also suggested Lystrosaurus, which may have had hair, was warm-blooded.

Hibernation is a form of torpor found in warm-blooded animals like certain bears, rodents, echidnas, hedgehogs and badgers.

Lystrosaurus, ranging from roughly the size of a pig to the size of a cow, possessed a turtle-like beak and lacked teeth except for a pair of ever-growing tusks protruding from its face useful for digging up tasty roots and tubers. These tusks had incremental growth marks visible in the form of dentine - the hard tissue that forms the bulk of a tooth - deposited in concentric circles like tree rings.

The researchers examined tusk cross-sections from six Lystrosaurus individuals from Antarctica and four from South Africa, away from the polar conditions. The Antarctic tusks bore closely spaced, thick rings suggestive of periods of less deposition during a hibernation-like state.

"Torpor is an incredibly common physiological phenomenon in animals today," said Harvard University paleontologist Megan Whitney, lead author of the research published in the journal Communications Biology.

"We expect that torpor has been a commonly employed adaptation for a very long time," said Whitney, who worked on the research while at the University of Washington. "However, this is difficult to test in the fossil record, especially deep in time hundreds of millions of years ago."

Such resilience may help explain why Lystrosaurus, which predated dinosaurs by millions of years, survived the worst mass extinction in Earth's history 252 million years ago, as the Permian Period ended and the Triassic Period began.