(Bloomberg) -- The solution to Europe’s next economic crisis might not lie with the European Central Bank -- or whoever leads it after Mario Draghi.

A future growth emergency risks proving overwhelming for the Frankfurt-based institution and its depleted monetary ammunition, potentially putting the onus on a fiscal response instead. That prospect of policy impotence may offer less glory to the central banker who replaces Draghi at the ECB’s helm -- and less of an incentive for countries to win the job.

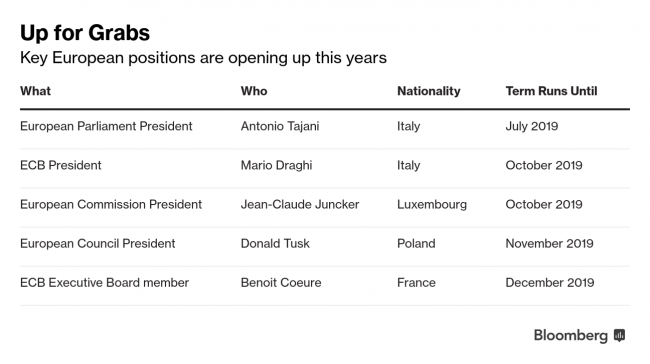

That perspective is one backdrop to the impending tussle over the European Union’s senior positions, including the presidencies of the European Commission and the ECB. The negotiation gives leaders a once-in-a-decade opportunity to influence the direction of the region for years to come. But with such top jobs unusually juxtaposed against each other, the central bank looks a smaller prize than it was.

“Monetary policy has broken pretty much all of the old taboos -- they’re normal now,” said Andrew Bosomworth, a money manager at Pacific Investment Management Co. “That means the Commission and the Council will be the more influential roles.”

Horsetrading among European governments over the top jobs will begin after this week’s European Parliament election, starting with a Brussels summit on May 28. As the bloc’s political center of power, the commission has long been the biggest trophy, though the central bank’s monetary clout made it one to be coveted too.

Germany is staking a claim for its nationals to lead either the ECB or the commission. France, with a longstanding tradition of seeking positions of leadership, may well do the same. That sets the scene for a standoff between the euro region’s two biggest economies.

The EU has witnessed such stalemates in the past, for example with France’s insistence on the appointment of then Bank of France Governor Jean-Claude Trichet to the ECB at its birth. This time, France has less of a claim to the central bank having previously clinched it, but possibly also less of an ambition to win it.

“The French want to shape Europe,” said Janwillem Acket, chief economist at Julius Baer. “They can do that better via the commission than the ECB.”

The commission is the bloc’s executive, enforcing rules on matters such as competition and antitrust, and proposing its legislative agenda, for example on further economic integration and banking union. The institution will also be at the vanguard of any response to escalating trade tensions with the U.S. -- a matter of vital interest to the region’s biggest economies -- and in negotiating a future agreement on commerce with the U.K. after Brexit.

Pivotal Role

The ECB under Draghi has been pivotal in keeping the euro region together during the sovereign debt crisis. It’s Outright Monetary Transactions tool, developed during that turmoil provides an important underpinning for the integrity of the single currency.

But now that it has bought government bonds in quantitative easing close to the limits of its rules, and cut interest rates well below zero, the institution is arguably a weakened economic actor.

Facing a resurgent economic crisis, the ECB could deploy a toolkit that has already been much expanded by Draghi. He claims the institution has the “optionality” to extend that array of measures with negative interest rates, long-term loans and asset purchases, if needed. But economists including Adam Posen, a former Bank of England policy maker, say that might not be enough.

“If we have another severe downturn, or even moderate downturn, it will fall upon fiscal policy to respond,” said Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

It’s hard to know what form that would take. In the case of a synchronized fiscal stimulus by national governments -- for example as deployed by the Group of 20 nations during the financial crisis in 2009 -- the ECB might be little more than an observer to the action.

A less conventional response, for example requiring a mix of fiscal and monetary policy, would require the central bank’s participation. Still, political institutions and elected representatives like the euro group of finance ministers might have to take the lead.

“If you have to resume QE or do something else, then you need someone who can make it politically appealing or credible,” said Frederik Ducrozet, a strategist at Banque Pictet & Cie.