By Geoffrey Smith

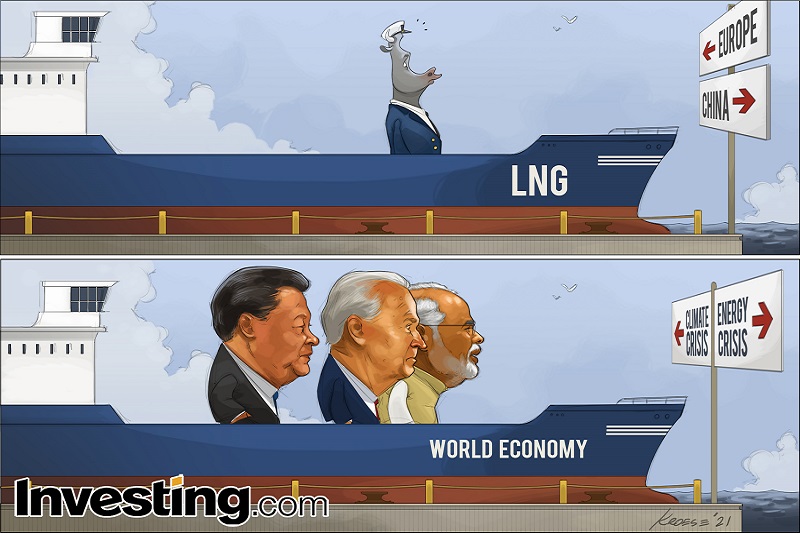

Investing.com -- The world has under-invested in fossil fuels because of an obsession with Climate Change.

The resulting shortage of supply and the vicious squeeze in global energy prices only shows that the price of Climate Change mitigation is unacceptably high.

For any further proof, witness the orgy of self-righteousness and self-congratulation that is about to explode at the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, an event that seems doomed already to failure, for all that the politicians there will claim otherwise.

Exasperation turns easily to despair when fuel bills are rocketing (everywhere), when gas stations are empty (as in the U.K.), when the power system responsible for keeping the lights on for 1.4 billion people is down to four days’ worth of fuel supplies (as in India), and when the only country that can solve your short-term energy crisis is a repressive kleptocracy that you would prefer to keep as far away from you as possible (as in most of Europe).

But despair is not inevitable and the current energy crisis – while it may be repeated – will not be lasting.

The current squeeze – which has introduced the global investing public to the Dutch TTF benchmark gas contract and Chinese coal futures – is a passing phenomenon. Much of it is due to the pandemic, which depressed coal output from South Africa to China and which delayed necessary maintenance of Russia’s gas installations last year. But the pandemic is fading, and so will these pressures.

Looking ahead, one can also be more confident that high prices will, as usual, be the cure for high prices, and that future regulations will be drafted to provide better incentives for backup power and more redundancy in infrastructure - especially in storage, the only solution to the problem of renewables’ intermittency.

Most importantly, the two countries that will drive Climate Change more than any other in the coming years – China and India – know that they cannot afford further unbridled growth in fossil fuel consumption.

For many years, the effective constraint on Chinese policy was pollution, and the public health emergencies created by smog from its coal-fired power stations. However, catastrophic flooding across various parts of the country this year has made it clear that extreme weather events are increasingly a threat to economic - and ultimately social - stability. UBS analysts point out that while 40% of the $210 billion in global climate-related losses last year were insured globally, only 2% were in China.

“When we protect nature, it rewards us,” President Xi Jinping said in a speech earlier this month, with a nod to those floods. “When we exploit nature ruthlessly, it punishes us without mercy.”

To be sure, such platitudes won’t stop either China or India burning more coal in the short term. And Beijing’s action this week to approve new coal mine projects in Inner Mongolia flatly contradicts President Xi Jinping’s stated ambition to reach peak zero carbon emissions by 2030, raising suspicions that Beijing will yet again back off any action that threatens short-term growth.

But China’s latest renewables projects – it is already building a solar farm in its western desert that will generate three times as much power as the Three Gorges Dam – are clearly much more than just tokenism: it already has more installed renewable capacity than Japan and Germany combined. The country is heavily invested in cleaning up and greening up.

The world’s progress toward a more resilient, greener global energy system can’t help but be chaotic, uneven and hampered at by economic competition between nations. But it is still nonetheless progress, and neither COP26, nor short-term market squeezes are likely to stop it.