By Geoffrey Smith

Investing.com -- For most of this year, the world’s central banks have been loosening monetary policy as fast and as far as possible. But with the first signs of an end to the pandemic in sight, is that trend now about to reverse?

In a word, no. At least, not in the developed markets of the world, which are still flagging that the next policy move is likely to be more stimulus rather than less. The European Central Bank has all but committed itself to easing when its governing council next meets, the Bank of England continues to flirt with taking interest rates negative as it nervously waits for a volatile end to the post-Brexit transition period, and the Federal Reserve is visibly chafing at the economic damage done by political paralysis in Washington over the last couple of months.

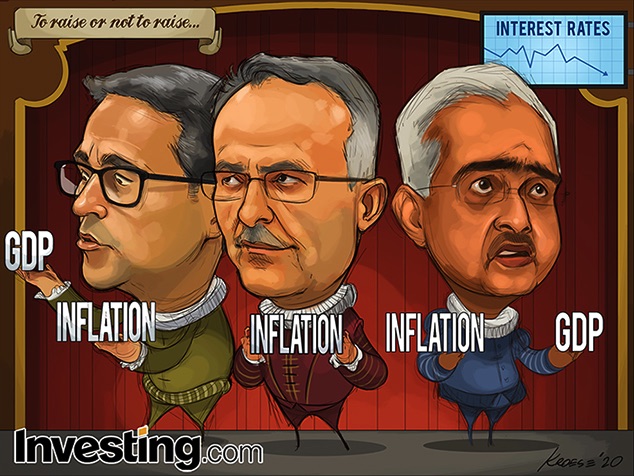

But in the world of emerging market central banks, the picture is much more nuanced. True, Indonesia and the Philippines both surprisingly cut their key rates earlier this month. But elsewhere, the old rule that emerging markets have to keep higher rates to keep inflation down is starting to reassert itself: Turkey finally acknowledged that it needed to raise rates aggressively to rein in an inflation rate running at close to 12%. Central banks in two of the world’s most important emerging markets, India and Brazil, may also decide they need to follow before too long.

The Reserve Bank of India’s policy-making council is due to meet on December 5th, and a rate rise is seen by some as quite plausible, in view of the pickup in inflation in recent months. The RBI cut its key rate in only two stages from 5.15% to a record low of 4% in the early stages of the year, but inflation had been on a rising trend going into the pandemic and that trend has returned forcefully in the last few months, the annual rate rising to 7.6% in October.

Likewise, the Banco Central do Brasil meets on December 9th, against the backdrop of an inflation rate that is going in the same direction, albeit less dramatically. Since June, when it bottomed out below 2%, inflation has more than doubled to 4.2% as of mid-November.

In India, food prices have been the main culprit, largely the result of unseasonal and excessive rainfall. However, government increases in fuel duty have also contributed.

In Brazil, the government is at risk of importing a growth slowdown from the U.S. and Europe, which account for over a quarter of its exports. China, its largest trade partner, still only takes a little more than 30% of its foreign trade. While its recovery from the pandemic is evident in surging prices for industrial commodities, it’s unable to support the Brazilian economy on its own, says Geoff Yu, Bank of New York Mellon’s senior EMEA foreign exchange strategist.

That's raising the pressure on the government to act again to support growth. But Brazil’s biggest problem is a gaping fiscal deficit caused by the generous income support to households during the early stage of the pandemic. While that has limited the economic contraction, it threatens to destroy the credibility created by the country’s self-imposed limits on fiscal spending in previous years.

The RBI is still the likelier of the two to move in December but, as analysts at JP Morgan wrote in a note to clients this week: "The risk is that fiscal measures are taken to support growth, undermining policy credibility and pressuring the BCB to tighten early,”