By Howard Schneider

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Hot U.S. inflation data has put the Federal Reserve's debate over a first interest rate cut on a potential collision course with the presidential election calendar, although a parade of top-level Fed-watching economists also predict the Fed won't make its move until after Americans go to the polls.

Rate futures markets now show investors see a first rate cut as most likely occurring at the Fed's Sept. 17-18 meeting after data showed inflation through the entire first quarter of 2024 was stiffer than expected and had demonstrably slowed progress on bringing it back to the Fed's 2% target.

A rate cut then - just seven weeks before Election Day - would shine a spotlight on the Fed, which goes to pains to keep itself out of the political tussle. Not cutting by then won't necessarily dim that light, though.

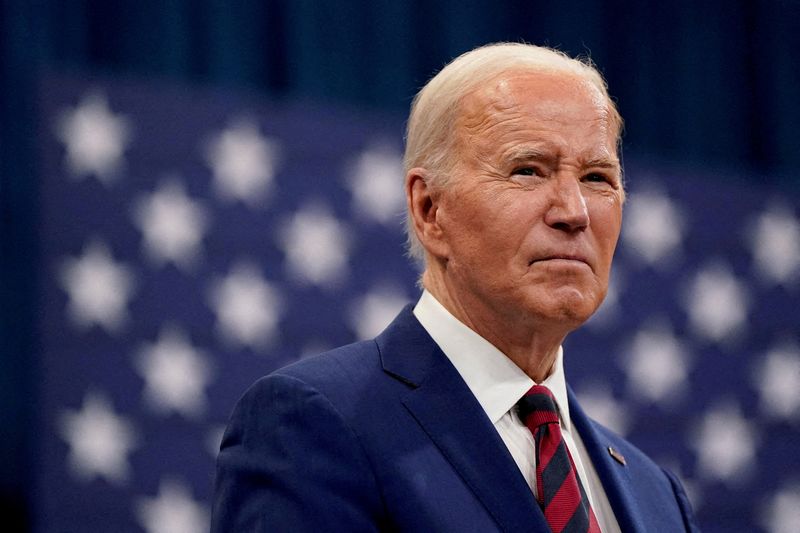

Fed officials are adamant their policy decisions are fully divorced from political concerns or influence - be it incumbent President's Joe Biden's hope for a soft landing of low inflation and low unemployment to carry into heart of the campaign season this autumn, or presumptive Republican nominee - and former president - Donald Trump's brewing argument that if the Fed cuts rates it will only be doing so to help his Democratic rival.

No Fed official has offered a potential start date, but policymakers' projections last month indicated on balance they still expected to deliver three, quarter-percentage-point rate cuts this year, an outlook first presented last December.

With that as a guide, investors for months had settled on June for a first cut, with the two other reductions staggered over the rest of the year. It was a timetable that had seemed well-phased around the hottest moments of the presidential campaign, but was thrown off this week when Consumer Price Index data for March extended a streak of unexpectedly strong readings, leading a growing number of Fed officials to say there would likely be no near-term move on rates.

At the same time, a core of professional Fed watchers now see an outcome where the Fed misses the presidential election cycle entirely, though that doesn't mean the central bank won't be a campaign focus.

In the hours since March inflation data came in hot, analysts from JP Morgan, Bank of America, Jefferies, Deutsche Bank and others tore up their prior predictions that rate cuts would be well underway by the election - a possible boon to Biden - and some pushed them back to year end or even 2025.

"We do not think the Fed will gain the confidence it needs to start cutting rates until December," Bank of America economists wrote, meaning Biden would be campaigning against the stigma of both higher borrowing costs and persistent inflation.

Biden, for his part, said he felt the Fed's baseline outlook for rate cuts this year would prove correct, even if recent data have thrown it into doubt.

"We don’t know what the Fed is going to do for certain," Biden said after Wednesday's inflation report, but "I do stand by my prediction that before the year is out there will a rate cut."