(Reuters) -Increasingly popular "earned wage" advances on worker paychecks are consumer loans subject to existing federal laws, the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) said on Thursday, moving to set federal guard rails for a fast-growing market.

In a proposed interpretive guidance, the agency said many paycheck advances were subject to the Truth in Lending Act, meaning the companies who provide millions of such loans a year must give workers clear disclosures about finance charges, among other requirements.

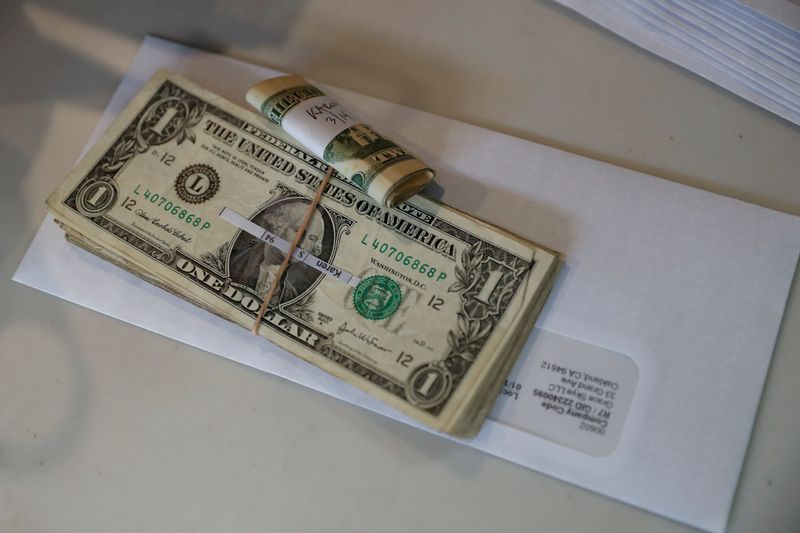

Many such workers are borrowing at high interest rates and incurring sometimes mischaracterized fees, according to the CFPB. In a statement, CFPB Director Rohit Chopra said his agency's actions would help wage earners "know what they are getting."

Greater transparency should also spur competition and help reduce costs, according to Chopra.

States such as Nevada and Wisconsin now license paycheck advance products, specifying that they are not loans. Prior to the announcement, CFPB officials said they expected companies to comply with federal law nonetheless.

A growing number of providers offer paycheck advances. Digital bank Chime said in May it would allow customers to access up to $500 of their wages interest-free before payday with no mandatory fees.

In a statement released overnight, American Fintech Council CEO Phil Goldfeder said he was "deeply disappointed" with the CFPB proposal. "Simply put, EWA is not a loan nor an 'advance' and should not be regulated as such."

According to a CFPB report also released on Thursday, workers using paycheck advances take out an average of 27 such loans a year and employer-sponsored advances typically carry annual percentage rates of more than 100%.

The agency said the number of such transactions nearly doubled between 2021 and 2022, when more than 7 million workers borrowed about $22 billion.

Thursday's CFPB proposal involved an "interpretive rule" rather than new regulations, which are subject to a lengthy approval process and can be struck down in court. Republican lawmakers have expressed frustration with the CFPB's use of such guidance instead of formal rulemaking.

A senior CFPB official told reporters prior to Thursday's announcement that before being finalized the interpretive rule was subject to a public notice-and-comment period due to close next month.