By Samuel Shen and John Ruwitch

SHANGHAI (Reuters) - As China struggles to wean its economy off excessive debt, fledgling securitization markets have exploded with cash-starved banks, local governments and private firms rushing to convert assets into cash.

China's market in asset-backed securities (ABS), a financing instrument via which a wide range of assets such as loans, real estate, toll ways and scenic parks have been converted into tradable bond-like securities, surged 50 percent in 2016 alone and now exceeds a trillion yuan ($147.1 billion).

But there are signs of risks building in this market, which barely took off three years ago.

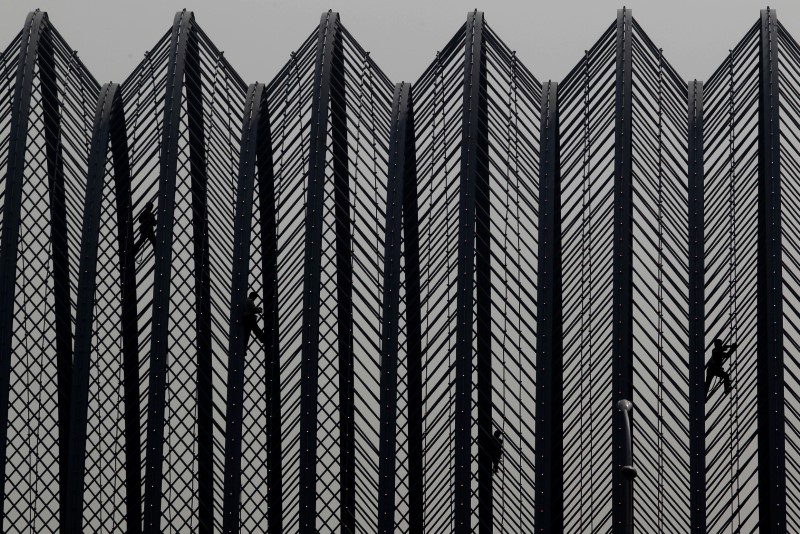

Its first default struck late last year when a securitized bridge in Inner Mongolia could not collect enough tolls to pay investors.

Analysts say some securitized projects have had over-optimistic cash flow projections, and in other cases there has been an excessive concentration of risk.

Chinese media reports have added to that worry by suggesting the government may soon lower the regulatory bar for government-backed infrastructure projects to be securitized.

"Asset securitization can help companies reduce leverage in a controllable manner and support the economy," said Song Qinghui, a Beijing-based independent economist.

"It's only a financial tool, but in recent years, ABS has been trumpeted to the sky in China, and the rapid growth of the business even shares some resemblance to the budding stage of the U.S. subprime crisis."

The securitization drive by the government ironically comes alongside China's stepped-up efforts to reduce its massive debt load and excessive investment.

It is in part responsible for pushing banks and real estate firms to try and convert the illiquid future receivables on their balance sheets into immediate cash.

The first batch of public-private partnership (PPP) projects was securitized early this year and included two water treatment projects, a tunnel operator and a heating facility.

A second batch of projects is expected to begin trading on China's two main stock exchanges soon, raising billions of yuan for the local governments that securitize the assets.

There could be more securitization of such PPP projects if the government changes rules that currently bar projects that have been in operation for less than two years from being securitized.

QUESTIONABLE QUALITY

China launched ABS in a pilot scheme in 2005, but suspended the market during the 2007-08 global financial crisis, which was triggered by the collapse of shaky mortgage-backed securities in the United States.

China resumed ABS issuance in 2012, and has issued a range of policies since to promote the business, with the State Council, or China's cabinet, identifying asset securitization last year as a way to help Chinese companies reduce leverage.

Financial regulators believe ABS could help China's local governments manage their massive 15 trillion yuan debt.

Lin Hua, chairman of consultancy China Securitization Analytics, warns however that it is the local governments with lower ratings or those in China's less-affluent regions, such as Guizhou, or Shandong, that would be tapping the ABS market.

Although in a typical asset securitization structure, a special purpose vehicle is set up to insulate the issuer's credit-worthiness from the underlying assets backing the ABS, there is also growing concern underwriters and credit rating agencies could paint an unrealistically rosy picture of the securitized assets' future cash flows.

That was the case with the bridge in Inner Mongolia that missed payments after its toll income collapsed due to a slump in coal transportation, a far cry from the stable cash flows projected by rating agency China Lianhe Credit Rating Co.

In February, Shenwan Hongyuan Securities Co was reprimanded by securities regulators for having made "inconsistent" due- diligence reports in several ABS deals that "lack adequate supportive evidence" and that failed to fully reflect the borrowers' creditworthiness.

Zhou Hao, president of China Chengxin Securities Rating Co, said brokerages paid more attention to winning the ABS underwriting business than to collecting future cash flows.

"Brokerages have poor management in collecting future cash flows, and there are also disclosure problems."

Bank of Tianjin issued an ABS in July 2015 that was created from loans to just 22 borrowers, with lending to Shandong Shanshui Cement Group, a struggling cement maker, accounting for 12 percent of the underlying assets.

In another case, the China Development Bank raised 5 billion yuan by issuing an ABS product backed by loans to just one borrower, state-owned steelmaker Shougang Group.

The big worry is that some underwriters and rating agencies could collude with issuers to package shoddy assets into risky, opaque and hard-to-understand bundles of products sold to an unsuspecting public.

"If assets of zombie companies are sold to investors in the form of ABS, with acquiescence from banks and regulators, that would be organized fraud," Wang Jun, finance professor at China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) told a forum in December.

(This version of the story has been refiled to change dateline)